From phoolgobi and phal, to mewa and mawa – writer Priya Mani traces the journey of our beloved meetha.

My earliest memories consist of making coconut barfi with my Amma as her little helper. She would start the process by breaking a coconut and scraping off pure white shreds of coconut meat. After which she would put equal parts of sugar and water in a large vessel and set it to boil. As the mixture thickened into a sticky syrup, Amma would stretch a dab of it between her fingers to make two fine silky sugar threads. From here, it went fast — the shredded coconut was stirred in, the walls of the pot scraped so each sticky morsel was salvaged. The mixture would come together slowly, ebbing rhythmically. Then there were final touches — a spoon of ghee and a pinch of cardamom that would envelop the kitchen in a heavy, sweet aroma, lingering in its warm air for hours. When the mixture cooled she carefully drew lines with a knife, cutting them in squares or lozenges. There were always odd strips, end bits, and uneven edges that were unfit for guests. These were rewards for us.

Throughout India and the rest of South-Asia, barfi is a visual shorthand for celebration, designed to be shared. There is always a barfi for all of life’s moments and milestones. A successful exam, an unexpected guest, a toddler’s first tooth, the announcement of a wedding; these are marked with a small, bite-sized barfi. It is the most versatile of desi sweets, owing its diversity to the ingenuity of the home cook.

In the domestic kitchen lab, several kinds of purees — nuts, fruits, dry fruits, vegetables, milk, yogurt, grains, lentils, pulses, and chocolate have found their way into sweet syrup. These have become beautifully plated barfi, gleaming with silver wark or chopped nuts. With barfi, you can eat with your eyes. In the 20th century, barfis were of several, uncanny types like Pragyasundari Devi’s kabisangbordhana barfi, a neat barfi of cauliflower puree that she made for her uncle, Rabindranath Tagore’s 50th birthday. When she revealed the real ingredients, Tagore’s guests were both shocked and amused at his niece’s audacious take on the sweet barfi. But unlike Devi’s barfi from 1911 or my mother’s barfi from the 1980s, almost all barfis call for milk today. Apart from a rare mawa barfi, milk is not an ingredient in barfi recipes in 19th & 20th century Indian cookbooks like ‘Pak Chandrika’ either, or in mid-century regional cookbooks like Meenakshi Ammal’s ‘Samaithu Paar’. In my curiosity to know what changed this quintessentially Indian sweet, I unearthed the evolution of barfi from fruit and nut fudges to milk-rich sweets.

In the 20th century, barfis were of several, uncanny types like Pragyasundari Devi’s kabisangbordhana barfi, a neat barfi of cauliflower puree that she made for her uncle, Rabindranath Tagore’s 50th birthday. When she revealed the real ingredients, Tagore’s guests were both shocked and amused at his niece’s audacious take on the sweet barfi. But unlike Devi’s barfi from 1911 or my mother’s barfi from the 1980s, almost all barfis call for milk today. Apart from a rare mawa barfi, milk is not an ingredient in barfi recipes in 19th & 20th century Indian cookbooks like ‘Pak Chandrika’ either, or in mid-century regional cookbooks like Meenakshi Ammal’s ‘Samaithu Paar’. In my curiosity to know what changed this quintessentially Indian sweet, I unearthed the evolution of barfi from fruit and nut fudges to milk-rich sweets.

The presence of milk and milk products in barfis today is linked to the milk milieu in late 19th and early 20th century India. Then, milk was produced by small milk producers who were plagued by challenges of adulteration, and unfair pricing practices by middlemen. Another challenge to milk production was that in India’s hot, torrid climate, fresh milk spoiled quickly due to poor cold-storage infrastructure. So surplus milk was often fermented into yogurt and made into butter. In North India, it was dessicated to milk solids locally called mawa or khoya. In all contexts, milk was precious food, a luxurious ingredient, for occasional use. Even as the Cooperative Societies Act of 1912 was enacted to resolve issues of sustainable and regular milk supply, it was not until 1946 with the formation of Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation, and their brand Amul that consolidation measures gained momentum. These were novel initiatives then, but paved the way for the availability of milk we take for granted today.

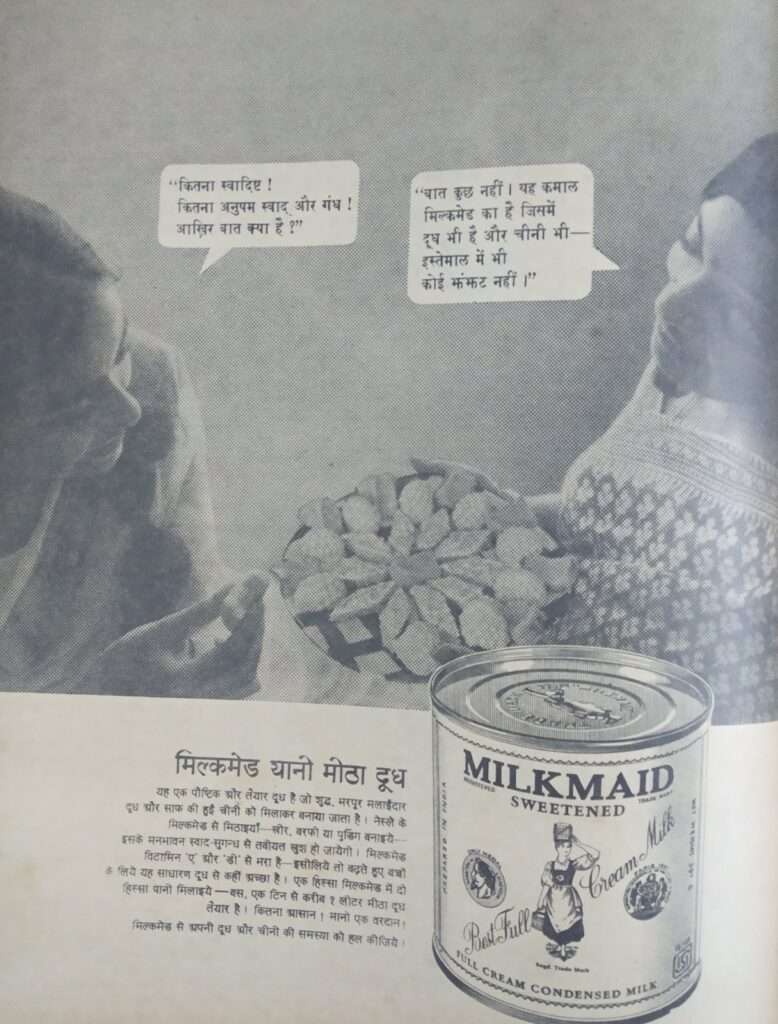

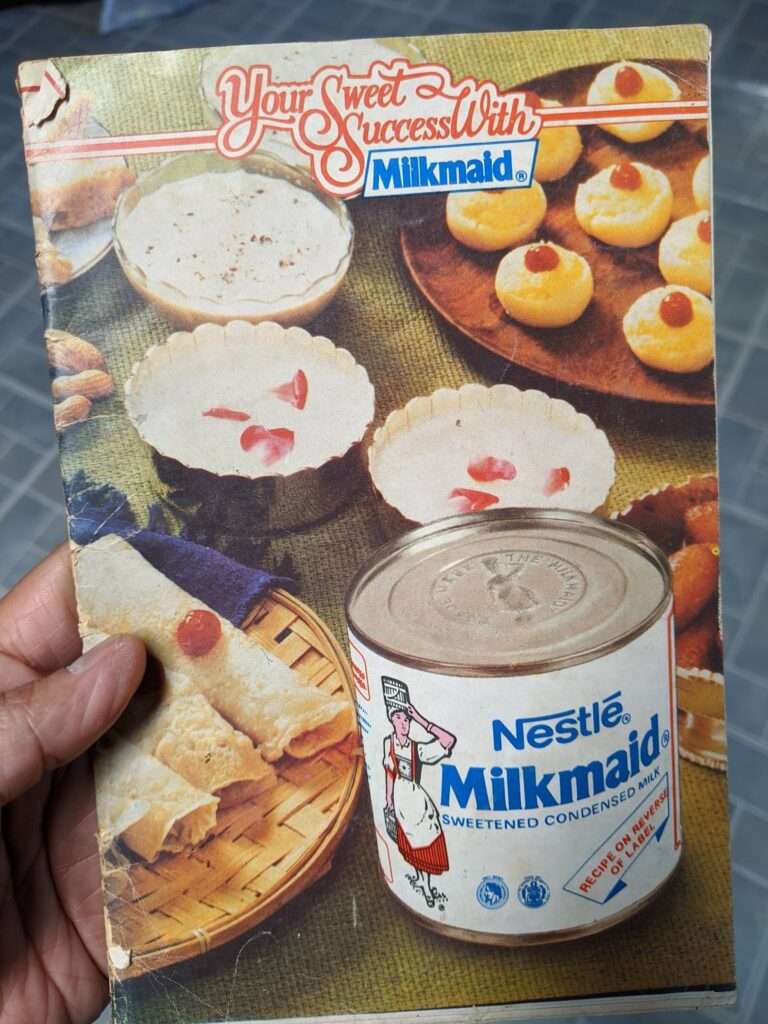

After India’s independence in 1947, domestic milk production improved with the success of Amul and other milk cooperatives. Milk and milk products became more easily available than ever before. But even before the centralisation of milk — condensed milk, a creamy, sweetened reduction of milk, often used by adding water, was sold as a safe option by companies like Nestle. Nestle’s condensed milk was called Milkmaid, which was sold in the country as early as 1912. But by 1980, because of competition from cooperatives, the market for Nestle’s condensed milk dwindled. The multinational had held considerable control of the market in India and this was a cause of concern. In 1984, Nestle entrusted their advertising partner Clarion-McCann with the task of improving condensed milk sales in India. On this task was a renowned ad-executive, the late Tara Sinha, who with her associate Joydeb Chakravarty realized that condensed milk was then largely used as a dairy whitener in milk and coffee. In what was a historic moment in barfi’s evolution, Sinha suggested that Indian mithai could be the perfect site for the rich sweetness and nutty umami of condensed milk.

In what was a historic moment in barfi’s evolution, Sinha suggested that Indian mithai could be the perfect site for the rich sweetness and nutty umami of condensed milk.

Herein started a fruitful campaign to insert condensed milk into sweet making—women’s magazine Femina carried recipes that used Milkmaid in mithai in their issues, blue labels wrapping the product’s encompassed printed recipes, putting the packaging to good use. These campaigns centered around the cook’s creativity, and as Nestle sold it, condensed milk was a time saving ingredient that resulted in superior preparations. When Amul launched their own condensed milk, Mithai Mate, they followed the same tactics, Nestle’s innovative campaign to their own product. The choice of milk — cow, buffalo or blend — offer both Milkmaid and Mithai Mate their unique viscosity and sweetness. Dishes like kheer, payesh or payasam can easily use a whole tin of gloopy condensed milk; or take rabri, which emerges denser and nuttier with it. And it is not without reason — condensed milk does not curdle when added to acidic ingredients. It also avoids forming crystals while cooking. Using condensed milk made a fullproof barfi, for a fraction of the time, effort and cost.

In India, milk had long remained a subtle marker of class, status and affordability. With an assimilation of industrialised milk products in sweet making, the treats and the techniques associated with them diversified in who can eat, cook and sell them. To this day, Amul, Nestle and many other condensed milk manufacturers continue to publish recipes and adaptations for condensed milk, and home cooks find inventive uses for it. Condensed milk is here to stay in the Indian kitchen as a delicious, efficient ingredient in the world of Indian mithai. Fast forward to today, as a mother raising my children in Scandinavia, I realize my children do not share the same taste for boiled and reduced milk as I do.. They still enjoy their grandmother’s old-fashioned milk-free coconut barfi, more than a barfi thickened and set firm with condensed milk. As India awakens to movements of veganism and dairy-free consumption, I thought about where these new trends would take our beloved barfi? Food bloggers have taken to re-interpreting a milk-free barfi enthusiastically. Some amass nut pastes or fruit pulps with plant-based fats and chill them before cutting them into lozenges. Others find a vegan alternative to milk made of oats, rice and sugar. But what amused me most was Vogue India’s recent recipe for vegan barfi. A young Mumbai confectioner folded a copious amount of rich pistachio paste into a thick sugar syrup to set his lush vegan barfi. And with that perhaps — the humble barfi has traveled full circle.

Fast forward to today, as a mother raising my children in Scandinavia, I realize my children do not share the same taste for boiled and reduced milk as I do.. They still enjoy their grandmother’s old-fashioned milk-free coconut barfi, more than a barfi thickened and set firm with condensed milk. As India awakens to movements of veganism and dairy-free consumption, I thought about where these new trends would take our beloved barfi? Food bloggers have taken to re-interpreting a milk-free barfi enthusiastically. Some amass nut pastes or fruit pulps with plant-based fats and chill them before cutting them into lozenges. Others find a vegan alternative to milk made of oats, rice and sugar. But what amused me most was Vogue India’s recent recipe for vegan barfi. A young Mumbai confectioner folded a copious amount of rich pistachio paste into a thick sugar syrup to set his lush vegan barfi. And with that perhaps — the humble barfi has traveled full circle.

Acknowledgements

The pieces of my barfi-puzzle would not have come together without the generous contributions of LV Krishnan, Joydeb Chakravarty, Dr. Subha Das, my mother and many home cooks who have patiently allowed me to interrogate them over the last year.