Through her many memories of chewing paan, Sangeeta Chakravorty explores the idea of what a folded, filled, fragrant betel leaf means across our subcontinent.

It is certainly not food, but is available on most street corners. Doubts about its categorisation notwithstanding, paan has an important place in a certain generation’s food memory palace, popularly known as nostalgia. (Paan is also sometimes translated as ‘betel quid’, which we can agree is an unimaginative name for this wonderful psychoactive drug.)

I grew up in Gwalior, Ujjain, and Bhopal – I grew up with the ubiquity of paan. That ubiquity is no longer assured. Not only has it become unfashionable to chew paan, but worse still, it has become part of curated experiences/experiments. (Think of the paan shop right outside the popular Mumbai restaurant Soam.) This was not always the case.

The slaked lime, the katha (acacia catechu), and the betel nut were a combination fit for the strong of will (which we were clearly not).

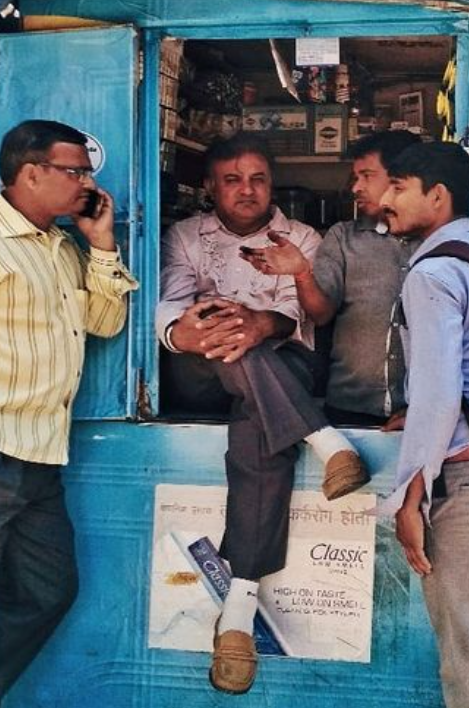

Paan shops have been corners that bring people together. When I say people, I mean men. Think about it: have you seen many women hanging around paan shops? For women, in smaller cities, asking for a paan at the paan shop can feel subversive. I know because I was the first woman in my family to buy a paan unaccompanied by a male member. The subversion felt deliberate – not just in standing exposed on a street, but also demanding customised pleasure.

There are different types of paan – wedding paan (the best kind), the type you eat in a city other than yours only to exclaim “mazaa nahin aaya”, the paan offered to the Gods, et cetera. The pressures of dwindling popularity and Instagram reels have turned the paan into performance art. Surely, we have seen fire paan, ice paan, and dosa paan amongst others. At the other end, there are stories of vending machines that dispense paan completely eliminating the street.

The first time I tried paan was at a winter wedding in Gwalior. Wedding meals those days were bookended by coffee topped with foam and chocolate powder; followed by a trip to the paan and churan counter. Unfamiliar with concepts such as gut bacteria and root canal procedures, the paan felt ever so delicious. It made all the kids feel grown up.

My second memory associated with paan is of my garrulous and disapproving maternal grandmother and her paandaan. A mother to five children and many grandchildren; she was tough with all of us. Her tenderness was reserved for the afternoons, when she allowed herself a moment of calm; and skilfully crafted her paan. She offered it to her favourite grandkids, but it was too much flavour altogether for many of us little ones. The slaked lime, the katha (acacia catechu), and the betel nut were a combination fit for the strong of will (which we were clearly not). This specific combination is so potent that it was highlighted as one of the main reasons for the corrosion of the mighty Howrah bridge in Kolkata.

Still, the memory of paan and the adulthood it promised did not leave me. Even so, an unaccompanied trip to the paan shop was out of the question for a very long time. I could not understand why something that is so commonplace (even in my own home where my mother offered it to the gods everyday) could be so forbidden to women.

Frosty relations between India and Pakistan have impacted the demand of the Tirur variety of betel leaf from Kerala.

The film Chashme Baddoor (1981), in which the suave Saeed Jaffery plays the role of a neighbourhood paanwalla with the biggest heart, holds a clue. Watching Mr. Jaffery speak in a Bhopali dialect, seeing him share the joys of eternally-in-debt wastrels always hanging around his shop, was a life lesson in itself.

Let me elaborate. Not much has changed since 1981 as far as the reputation of paan is concerned. Recently, the Maharashtra Congress chief Mr. Nana Patole indirectly made a dig at the ill repute of paan shops when he said, “He spoke as if he was at a ‘paan tapri’”, in reference to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s speech in Parliament. Even the then Pakistani Prime Ministerial candidate Shehbaz Sharif had promised that he would change the “paan-chewing Karachi into Lahore”.

It is not only ill-repute that threatens paan shops. The betel leaf, a water-intensive crop grown mostly in West Bengal, other eastern states, and south India, has been dealing with the ravages of climate change. The heatwaves (with the maximum temperature being in the mid-forties) have wreaked havoc on this cash crop in the last few years. The People’s Archive of Rural India, in an extensive report “Extreme weather plays havoc with Magahi paan” detailed the desolation that awaits the paan cultivators of India.

Paan cultivation has, traditionally, been the domain of the Barai and Tamboli castes (synonymous with the Chaurasiya caste), which have been identified as Extremely Backward Castes in the Caste Census done by the Bihar government in 2023. The economic status makes it harder for the paan growers to fight the costs of climate change.

These challenges are further compounded since the cultivation of paan falls under the horticulture department (as opposed to agriculture). The latter has more distinct policies with respect to crop insurance, a protection that is inaccessible to traditional paan cultivators.

The export of the betel crop is marred by the levy of ‘18% GST on air freight’. Frosty relations between India and Pakistan have impacted the demand of the Tirur variety of betel leaf from Kerala. Pakistan was the major consumer of this variety from Kerala; Bangladesh is now fulfilling this supply.

Popular culture in India is littered with references to the humble-mighty paan. The one that lingers, as long as katha on a tongue, is the tender moment of intimacy between a couple in Rohinton Mistry’s otherwise relentless novel, set during the Emergency in Bombay, A Fine Balance. It’s a nightly ritual between the husband and the wife; it’s a ritual that inhabits my memory palace.

When I started writing this article on paan, I had meant to write it as a story of small acts of defiance as a woman. The experience of finding my bite of customised pleasure at a paan shop in New Market in Bhopal. The same place I have been visiting since I was a law student. But the humble-mighty paan is a much better storyteller than me. For example: the Maghai paan vine; considered the king of betel leaves, produces a mere 50 leaves in a year. So hopefully, you will walk to your nearest paanwalla (as unlikely as it is that he will be as charming as Mr. Jaffery) sometime soon; and, in time you will find your own customised bite of pleasure. And, hopefully, an act of defiance.