The Parsi community has the most well-defined breakfast in India, argues Kurush Dalal, and he tells us about its many influences

“Breakfast is the most important meal of the day”, I probably heard my mother say this more often than anything else. She was an extremely pro-breakfast person, and her idea of a breakfast ranged from the extremely simple to the most ridiculously elaborate.

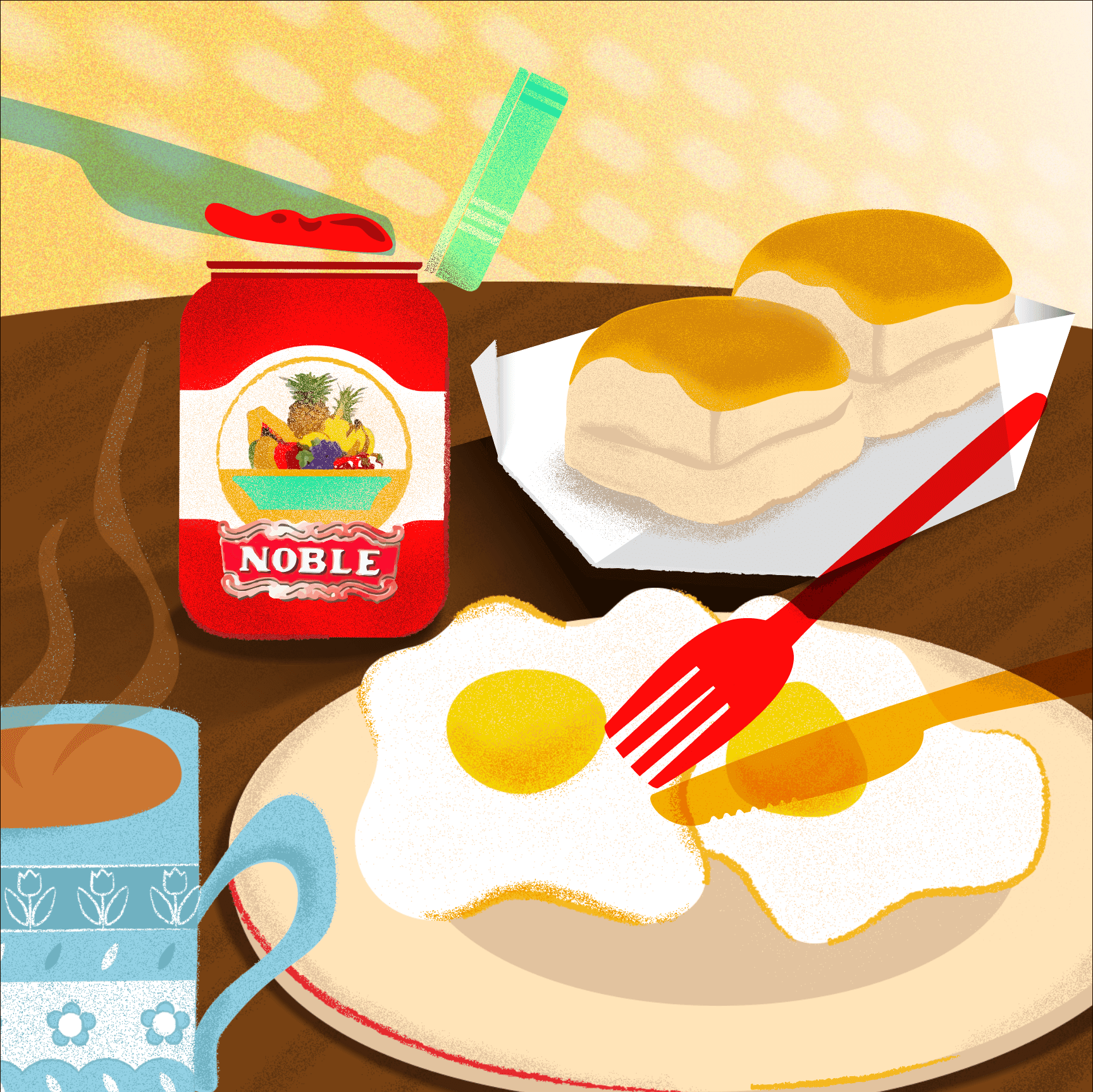

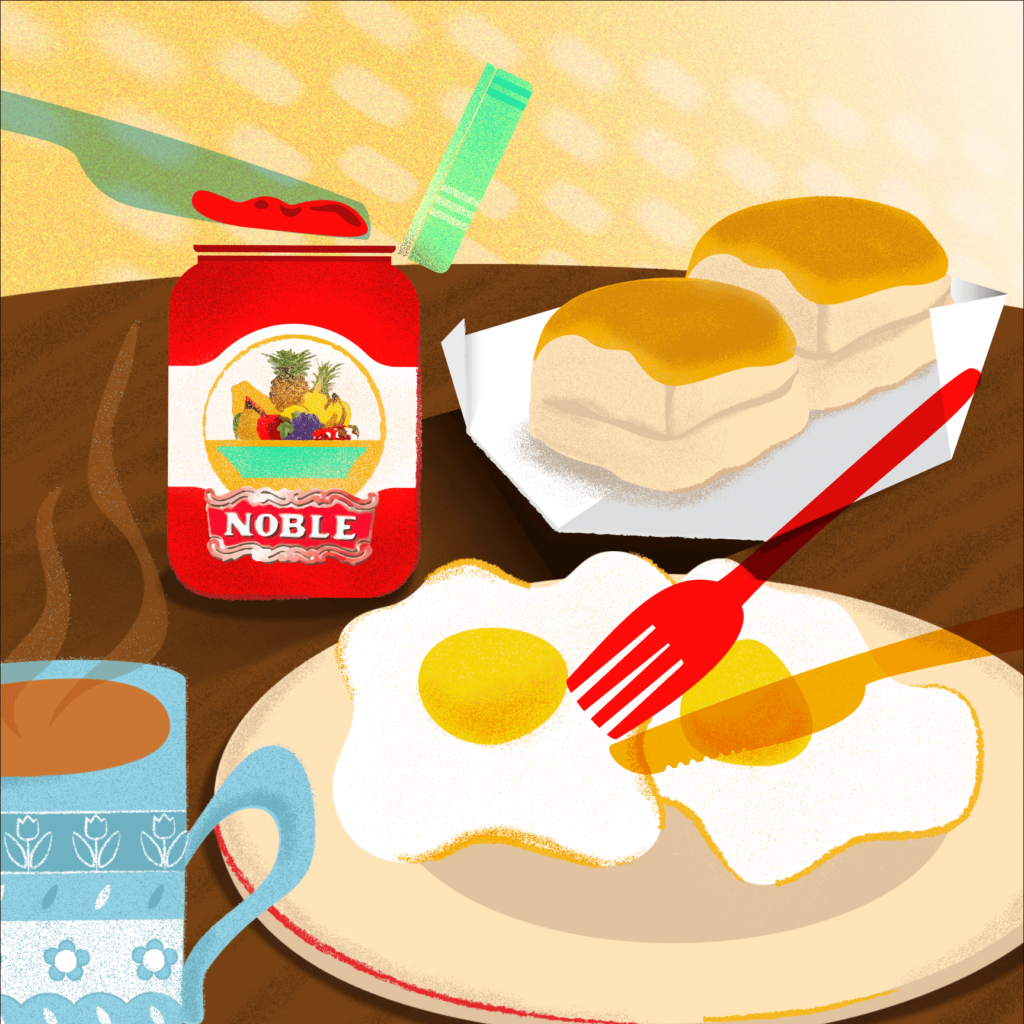

Growing up in a middle class Parsi home in Mumbai, on most days my breakfast was simply two fried eggs, bread with butter and jam on the side, and a large mug of milk. The bread was gutli pav from the nearby New Grand High Class (Irani) bakery whose bidi-smoking owner was a dear friend of my grandfather. The butter was Polson’s from their main shop in Polson Building around the corner, and the jam was usually Noble Mixed Fruit that came in one-kilogram cylindrical containers. The jam was essentially papaya and banana, with whatever else was affordable, and a high hit of sugar and maroon colour. Its memory brings that taste back to me even 30 years after I last ate it.

Holiday breakfasts were more elaborate. Parsi poro (masala omelettes with ginger garlic paste), cheesy scrambled eggs, akuri, along with brun pav, butter, jam, and perhaps some cold cuts like ham, luncheon meat, bacon, or sausages. Parsi festivals, and events like birthdays and anniversaries, all demanded a very different, traditional breakfast. Like ravo – semolina roasted in ghee and slow-cooked with milk, sugar, and often eggs, at a very low heat with enormous amounts of elbow grease, which was then sprinkled with sliced ghee-toasted almond slivers, and kismis. Or Parsi sagan ni sev – vermicelli that was slow-fried in ghee until dark brown, and then cooked in sugar syrup and sprinkled with charoli and kismis that had been fried in ghee. Sev was usually served with mitthoo dahi – a sweet curd made with reduced milk that is similar to mishti doi. Boiled eggs and bananas were the usual accompaniment to either ravo or sev (but never both) breakfasts. I have no idea why we served this combo but it was always thus. These were also foods that were sent over by and to neighbours during celebrations, and were both much looked forward to.

I agreed with my mother. Indeed, breakfast was the most important meal of the day, and I loved breakfast.

It was only in college that I was exposed to what ‘others’, i.e. non-Parsis ate for breakfast – and those breakfasts left me very perplexed, to say the least.

My friends from southern India waxed eloquent about idlis and dosas. My Maharashtrian friends talked about poha, sabudana khichdi (eaten on Tuesdays and Thursdays), and uppit (savoury semolina lovingly called concrete for the way it sits in your stomach). My friends from Bihar and UP surprised me the most. All of them seemed to live on a bowl of raw sprouts. Redemption was found in the kitchens of my Punjabi friends who ate hot butter-laden parathas stuffed with all manner of veggies, often kneaded in the previous night’s leftover dal. The Bengalis had their luchis, rutis, and porotas (all Bengali breads) served with a torkari, often accompanied by a sweet meat. They also ate bread, eggs, and jam for breakfast. The Gujaratis were the most interesting. They ate tonnes of naashta – kachoris, theplas, ghughras, chakli, chivda, and chutney sandwiches – downed with spicy masala chai. When they were on holiday they ate fafda or samosas with jalebis, from the nearby farsan or mithai shop. Now, all of these breakfasts are merely naashta – they can be eaten at any time of the day (barring the anglophile Bengali bread and eggs). To me, only one of these was specific to breakfast. In fact most of India ate just two meals!

Let me explain. Goan choriz can be eaten anytime of the day, as can Gujarati farsan and Punjabi paratha. Dosas, idlis, and vadas are consumed throughout the day in southern India, and relished all over the north. The typical Muslim saalan is a leftover from the night before.

But its only on a heaving Parsi dining table that you will encounter, only, and only, at breakfast – hot buttered toast or brun pav, marmalades, murabbas, jams, akuri, Parsi pora, and all manner of eggs with sausages, bacon, and ham, and even some hot ravo or sev on the side.

Every dish in this proper Parsi breakfast has made a fascinating journey to our community’s tables.

The Persians are the first chapter of this story. Persians, very much like the Islamic world, have had a three-meal-a-day system, with the morning meal being made up of murabba (fruit preserves), ponir (cheeses), and eggs served with various breads. The Parsis brought this culture with them to India where they quickly modified their ‘breakfast eggs’ to suit the availability of local ingredients. From this the akuri and the Parsi poro were born. The naans of Persia were replaced by chapatis, the ponir was dropped, and the murabbas were now made from a variety of Indian fruits and vegetables. Their love of lamb ensured that Parsi wedding breakfasts were truly spectacular, with offal from freshly slaughtered animals cooked with spices for a hearty breakfast dish. This dish, the aleti-paleti, has liver, kidneys, spleen, heart, and lung, all diced and slow cooked in spices.

The advent of the Europeans added a new layer. Many Parsis journeyed to Surat to work for them. The Dutch, the Portuguese, the French, and the British, all had factories in the region, and the colonisers craved for the foods of Europe.

My community’s lack of taboos in working with the Europeans suited them well. The Dutch set up a bakery and it was soon populated by Parsis. The Portuguese brought the pav to India (and the very word ‘pav’ is Portuguese for bread). The Parsis took to this bread so well that when the Dutch left Surat, one enterprising Parsi genius called Dotivala took it over. His family runs the bakery to this very day. Bread became part of the Parsi breakfast repertoire.

The British were the last stop on the journey of the Parsi breakfast. When they set up shop in Bombay, Parsis flocked to the city. Three huge waves of shipbuilding, cotton, and banking industries brought thousands of Parsis to Bombay, and threw them into contact with the British. From the Brits, us Parsis relearned the love of jams, and clandestinely fell into bed with ham, bacon, sausages, and salami. Soon, we couldn’t start our days without a cup of tea and a hearty, meaty breakfast.

Bread, butter, and eggs are now the fundamental building blocks of the Parsi breakfast. Our food is tempered with the spices of Gujarat, and accompanied by breakfast meats. The journey of the Parsi breakfast from Persia to Sanjan (Gujarat), Surat and Bombay is now over. Truly of all the peoples of India only the Parsis take their breakfast so seriously.

Dr. Kurush F. Dalal has an MA in Archaeology as well as a PhD on the Early Iron Age in Rajasthan, both from Deccan College, Pune University. He has excavated the sites of Sanjan, Chandore and Mandad and also actively works on Memorial Stones and Ass-curse Stones in India while dabbling in Numismatics, Defence Archaeology, Architecture, Ethnoarchaeology and their allied disciplines. He has blended his passion for food and archaeology into a research in Culinary Anthropology and Food Archaeology.

Illustrations by Megha Shah