Could an evening of strolling through two old Mumbai khau gullies be made into a movie script? A screenwriter gives it a shot.

SCENE 1.

The man behind the counter raises his head at the plainness of the order. Bombay is all about the option, the value-add, the combination. Cinema, the city’s most improvised and unreal creation, is sold to financiers via ‘packages’ featuring heroes and heroines who have proven bankable in the past, but also those that have never been seen together. Variety is this city’s game, and when it comes to street food, outlandish combinations are the standard. Not only can you get a ‘Chinese dosa’ featuring noodles, but you can get it crispy, with cheese, or even, to use an exclusively local phrase that over-promises heat, “Double Szechwan.” One dragon isn’t enough for Maximum City.

When, therefore, my friend stands at the legendary Lenin Pav Bhaji Centre and orders a straightforward “butter pav bhaji,” forsaking any unholy frills, the man behind the counter gives her a respectful smile. We are smack dab in the middle of Marine Lines’ Khau Galli, a collection of densely packed food stalls, next to the Income Tax offices and close to local train stations – a land of confusingly long menu cards, and all too many choices. As the smiling gent serves us a superb bhaji, scarlet enough to please the Soviets, with butter-gleamed pavs, the lesson is clear: those who know keep it basic.

SCENE 2.

It’s a hot October evening. The bustle around the food stalls is constant, a humid stream of humanity undeterred by sweat as they make and consume their selections before walking through the Maidan and past Fashion Street to take a train home, carb-loading before braving more aggressive crowds. This is not a galli for tourists or makers of Instagram reels, but one for serious eaters. Hawkers entice, but only call out the one time, instead of persisting incessantly: sirens know their audience.

I look past those making drinks — brown parabolas of tea showily tossed from glass to glass to be served in tinier glasses, juicewalas mixing up elaborate and suspiciously green drinks, a chhaas-maker going calmly about his work — to see how exclusively vegetarian this world is. I’m arrested immediately by a cafeteria-wide stall. Eponymously sharing its name with its address, ‘Khau Galli’ offers plates of mutton, chicken, offal, and dried shrimp for 8 to 120 rupees. I walk up tempted, but am waved away by the man wiping the counter. All that is lunchtime-only, at this hour they can only offer bread pakodas and the like.

I swivel, instead, to yet another snack place — one that offers pasta not only in white and red sauces but also in a pink sauce, a sort of rosé, if you will. We sit on a stool apiece, using a third one as our table, a table quickly weighed down by a grilled Bombay sandwich smothered in cheese. The big green dot denoting vegetarian food looms large on the sign of the sandwich and pasta place, but right next door, shredded chicken is being roasted on a spit. Two women in burkhas talk up a storm as they eat large shawarmas. Everything goes with everything else. Stomachs are as secular as a Manmohan Desai film.

SCENE 3.

Over at Nariman Point, the crowd is different. The hawkers gathering around Jamnalal Bajaj Marg serve office-goers and not commuters. The vibe is, therefore, a touch more laidback, with dosawalas taking the time to share laughs with customers and purveyors of pani puri patiently listening to finicky customisation. Those who work in nearby buildings — mostly banks — have stepped out for a break, and are clearly in no rush to leap back to their desks.

A few young women discuss something in conspiratorially low voices near a chana-jor-garam seller, and next to them, a man haggles to buy a glass screen to protect his smartphone. We eat an excellent and crisp plain butter dosa, then down a batch of delightfully tart panipuri. Finally we end up at the paanwala next door, where I notice Parle biscuits in a “Dal Chini Cinnamon” flavour, biscuits manufactured for the express purpose of stirring and being dunked into masala tea.

A man carrying a sack of things — like an out-of-season, out-of-uniform Santa Claus — comes up to us and tries to sell me AirPods. The shrink-wrapped boxes look like Apple’s own but he’s charging a zero less than market price, claiming they’re smuggled but perfect. I smile at him, impressed by his prompt profiling. I tell him I already have headphones and he suggests that they’d make a good gift. We both know they aren’t real, but it’s good to play along.

SCENE 4.

The sun is slithering down. The streetlights have been brought into play, instantly casting the street food hawkers in a more dramatic light. The area looks more cinematic now, in a grimy, Anurag Kashyap movie sort of way. The office crowd is thinning. There’s a perceptible drop in the number — and timber — of the voices. Perhaps people are instead paying attention to the sounds of food itself: the clanging of spoon against tawa, the tapping of knife against wood, the loud tear as ubiquitous packets of Maggi are ripped open, and the rustle of food being wrapped in newspaper. Or perhaps their mouths are full.

It’s still hot, but a mild breeze floats in from the sea, making it a fine evening for a stroll — particularly after having eaten a week’s worth of snacks in less than two hours. I’m immensely stuffed, yet can’t resist the lure of the one thing I’ve never tried before. Green chana chaat, a Marine Drive classic. My friend tells me this is the healthiest of street foods, and the counter features a wall of green chana, tomatoes, and limes, all sprayed with water for the illusion of freshness.

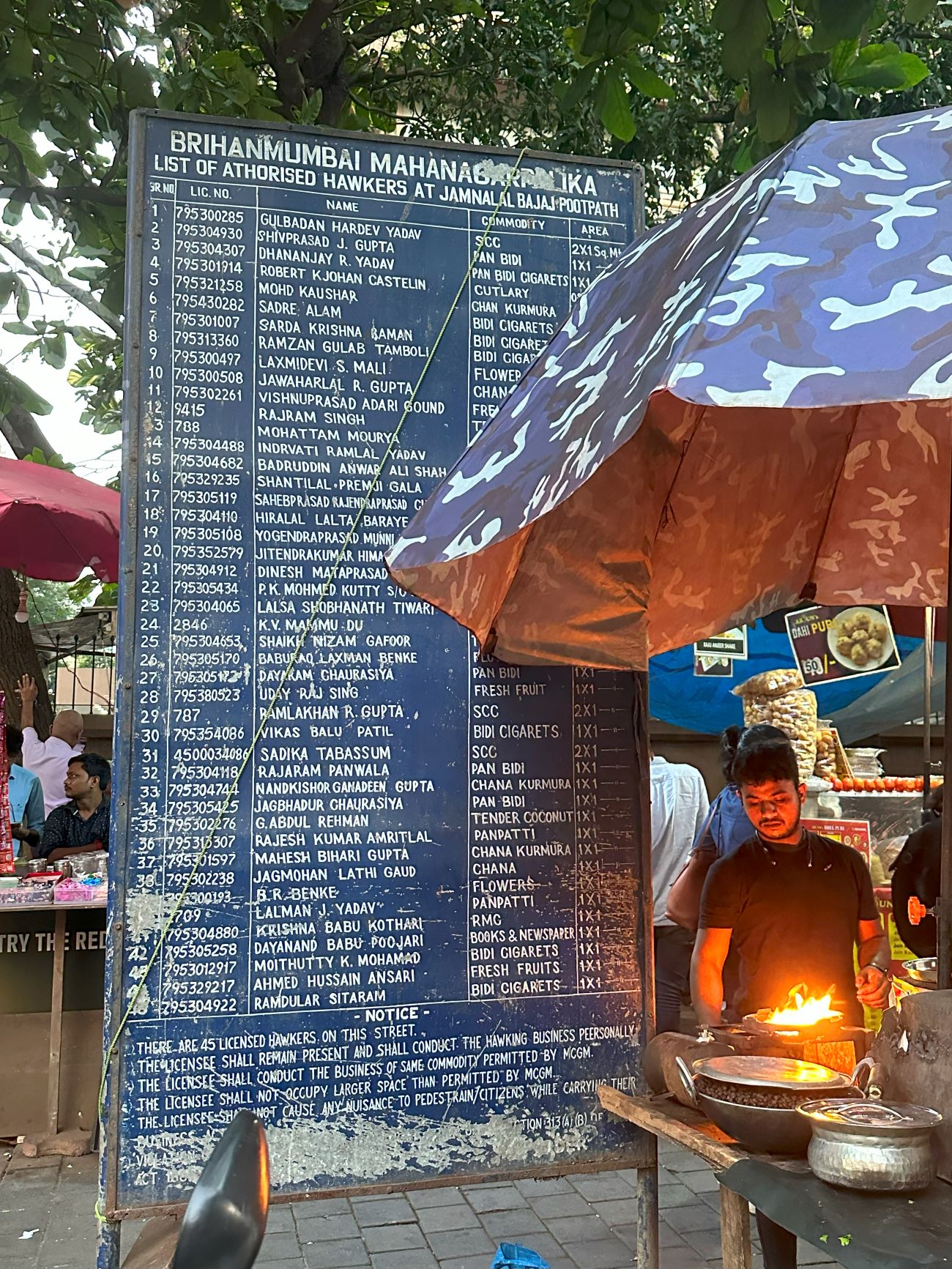

The trick works. We order a plate and the young man brews us up a batch, standing under a tall blue sign listing the “authorised hawkers” of the area. The sign is fantastic, listing “Bidi Cigaret” sellers like Ramzan Gulab Tamboli and Moithutty K Mohammed; Robert John Castelin who sells “Cutlery”; and Nandkishor Gamadeen Gupta who sells “Chana Kurmura.”

Beneath the blue sign and under a blue umbrella, a pot of long-stewing green chana bubbles. The vendor cuts up tomatoes and greens and serves the chana, no longer green. The chana juice has soaked up the masala, and the chana itself goes brilliantly with the diced tomatoes and the sprigs of green. The chaat is fresh and delicious, easily the most fun thing I’ve eaten all evening — which really is saying something. We have, inadvertently, saved the best for last, but what is truly staggering is that the healthiest thing we ate was also the most memorable. Now there’s a plot twist.