We’ve heard of soju, sake, and even chhaang. Analina Sanyal says it’s time we also paid attention to handia.

“Go to the land of red soil,

Where you’ll find handia and madol”

So goes a 1970s folk song, with lyrics penned by poet Arun Chakraborty. My childhood was spent humming it with my father, but I never understood what the lyrics really meant, until much later. Now I know that it talks of belongingness and about embracing where you’re from, illustrated through the themes of our regional liquor and our percussive instruments.

That brings me to the hero of this story – ha-nd-ia (also handiya, or hadiya). This is a traditional rice-based liquor consumed in various parts of India – across Rajasthan, Assam, Jharkhand, Bihar, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and in my very own state, West Bengal.

Many Indians are no strangers to liquors made with rice. In my corner of the world, we have handia which is a cousin of the rice beer, chhaang. And while you’ll rarely see a city mouse reach for homemade country liquor made with leftover rice, the outskirts and villages are filled with avid fans.

Further on, I will explore the roots and branches of the humble handia, which finds mention in folk songs and myths. I’ll also draw parallels to the consumption of soju and sake, and examine the factors that elevate one type of liquor over another even though they come from the same base ingredients.

Handia is as old as the existence of the consolidated Santal community. The Santals are a sub-group of the Munda ethnic people, who make up a large part of the tribal population in West Bengal and Jharkhand, and also reside in Bihar, Odisha, Assam and Tripura. According to Santali myth, the divine creator passed down the recipe to the first pair of humans, who then prepared it and served the deity. To this day, when handia is prepared for religious ceremonies, women will make it a point to bathe and wear fresh clothes before starting the process.

A decade ago, I was an intrepid teenager on a school field trip to Shantiniketan. Armed with a notebook, a questionnaire, and the spirit of anthropology, I went on to interview locals there.

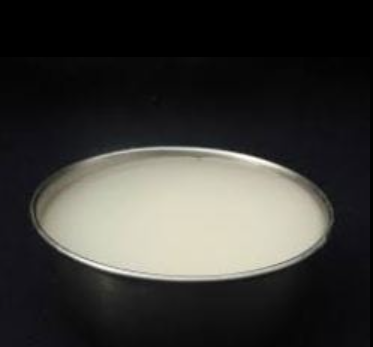

Shanitineketan offers an ideal pastoral setting – mud houses, red soil as far as the eye can see, and plentiful crops. As a city dweller, it was hard not to romanticise the setting I was in. I traipsed through pouring rain, and spoke to farmers holding a bhar (earthen cup) containing a cloudy white liquid. That’s when I first got my first introduction to handia – our fermented rice liquor. It derives its name from the vessel it is prepared in, a mitti ki handi, or earthen pot.

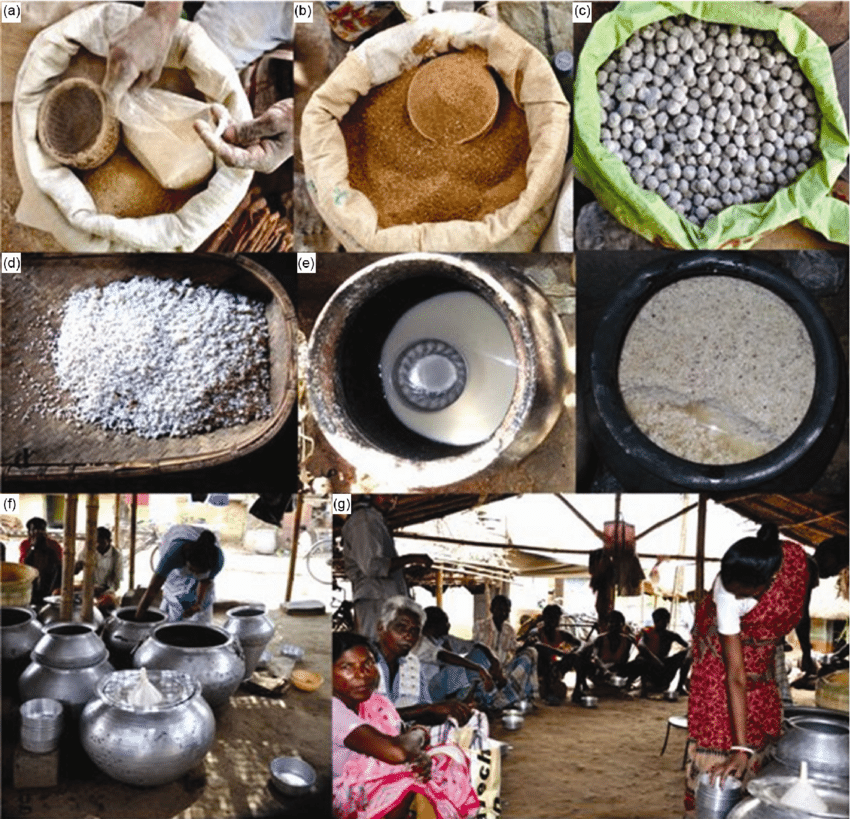

Image Credit: Panda, Sujogya & Bastia, Akshya & Sahoo, Gunanidhi. (2014). Process characteristics and nutritional evaluation of handia -A cereal based ethnic fermented food from Odisha.

While traditionally, the drink is prepared by the Munda and Santal communities – both camps claim first rights. Here are the five steps to making handia:

- Boil one part rice and two parts water

- Dry the cooked rice

- Store it in an earthen pot for a few days

- Add bakhar/ranu tablets (a starter, like sourdough culture)

- And then, store it in the closed earthen pot in semi-darkness.

Following these steps, what we get is a sour, mildly alcoholic drink with a frothy, creamy texture. It can be enjoyed chilled during scorching summers, or served warm through chilly winters. Its natural fermentation process gives the drink its characteristic texture. Some recipes may incorporate jaggery or sugar for additional sweetness, while others may use different varieties of rice, or vary the ratio of rice to water, for a thicker or thinner consistency. A varied choice of herbs and spices can also be included, depending on regional preferences and availability.

I was most fascinated by the starter tablets, essentially dried dough made from roots, barks, leaves, and stems of various trees in the area. These were what kickstarted the fermentation process which gave handia its alcoholic tang and taste.

On my visit, I realised that no farmer was about to provide detailed steps of alcohol production to a small teenager, despite her insistence. All I got from one kind soul was that it’s made in pots and drunk during festivals, rituals, weddings, or just to wind down after a long day. The rest of the information I gathered from online reading, and from people in my father’s ancestral village who also regularly consume the drink.

Today, a few years later, I’m less inclined towards romanticising rural life. I can perceive the difficulty of farmers’ circumstances, especially with the soaring temperatures across the country. Alongside, with deforestation and other unsustainable practices, the produce used to source the ranu or bakhar tablets are diminishing in number. Plants used for the tablet production are rampantly cut, sometimes smuggled without further planting, and slash and burn cultivation is followed in several places. So markets are now inundated with adulterated tablets.

Which is deeply unfortunate because traditionally, all the original ingredients were chosen for their medicinal properties – which might also explain why the drink and its brethren are so prevalent across India. I say prevalent, even so this is true for only one section of the society. You won’t see urbanites discuss the latest Dune film over handia anywhere. Wonder why?

Old Monk and Jack Daniels have their cults, but the drinking crowds are all for trying new age gins and juices. With the East Asian wave, sake and soju have infiltrated the market as well.

India is thirsty for alternative alcohol. In the past few years, adventurous foodies and alcohol consumers have taken quite a shine to sake. With the explosion of Korean culture among Indian audiences (or the Hallyu wave as it is called), soju has also found its fair share of admirers. Both sake and soju are not dissimilar to handia – they’re all liquor made with rice, water, and a fermenter or starter. In their case, it’s koji and nuruk in place of ranu or bhakar.

But handia, like other country liquor, is viewed as inferior to the exotic soju and sake. I can draw parallels to how fast-food chains are viewed in the USA, versus how they are seen in India – as budget dining and fancy meals respectively. These local liquors and their audiences hint at the class dynamics in our country. People higher in the social strata might happily adopt a rural brew if it arrives from across a foreign border, or with an international endorsement and a higher price tag. But they might view local rural drinks as unsanitary, or uncouth, at least for daily consumption.

As a colleague explained with some alacrity, “I’ll have handia if I’m in the countryside and want to get a taste of the local offerings, but I can have soju in a social setting to showcase my knowledge of world cuisine.”

From where I see it, this is a matter of mere marketing. From what I’ve learnt, handia is a cooling drink which can be used to treat jaundice, provide nutrition during hard days of working the field, and is overall pretty damn tasty. So to see it as inferior in any way is a pity, especially if you’re a true connoisseur of all things liquor.

Of course, undistilled rice beer need not be everyone’s cup of tea, and it is true that some are indeed more sensitive to the kind of water used for making a drink than others. For those who are up for it though, there is much to discover in our own backyards if given the chance.

Following the refrain of my childhood song, let’s go back to our roots – there’s handia and madol, and nowhere feels like home as much as the soil that we know is our own.

Citations:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhHUPsye8mg

- https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/bitstream/123456789/26030/1/IJTK%2013(1)%20149-156.pdf

- https://indroyc.com/2017/09/02/handia/

- https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/the-popular-adivasi-food-and-drink-47374

- http://www.anthrobase.com/Txt/S/Satpathy_N_Satpathy_R_01.htm