Lizzie Collingham, the author of ‘Around India’s First Table’, gives us a glimpse into her book, and her time in the kitchens of the Rashtrapati Bhavan.

enthu: Hi Lizzie! Thanks for talking to us. Let’s get to it — how was your time in the kitchens of Rashtrapati Bhavan?

enthu: Hi Lizzie! Thanks for talking to us. Let’s get to it — how was your time in the kitchens of Rashtrapati Bhavan?

LC: I was there for four weeks! And it was lovely. I mean, I didn’t attend as many presidential banquets, of course. But I really loved hanging out in the kitchens with the cooks. They were all delightful.

enthu: Can you tell us what these kitchens look like? How are they placed in the vast structure of the Rashtrapati Bhavan?

LC: So you go down to the basement, and then there’s a long corridor. And off the corridor, there’s a storeroom with all the goods — a pantry kind of thing. There’s the little room where all the ledgers are kept where they write down the food going in and going out. Then there’s a kitchen for the savoury stuff — the lentils and kebabs, that is divided into two with a big wall in the middle — I think they do kind of vegetables on the left and meat to the right, it’s segregated. Then on the other side of the hall, there’s a bakery where they make the cakes and the pastries and the bread.

enthu: A whole bakery?

LC: Oh yes. So they’ll be constantly making cakes. The kind of nursery food that I hadn’t seen since I was a kid, like jam roly polys, and elaborate sponge cakes with icing and things. All left behind by the British, of course. Good for me, though! Every time I went, the cooks pressed several slices of these cakes on me.

And then up at the end of the corridor there is a little room, a halwai. Here large cooks were constantly stirring a huge vat of milk curdling it to make sweets, or they were squeezing jalebi paste into hot oil, and dunking the fresh jalebi in rosewater, or doing something equally delightful. It felt as though they were always making sweeties. So who’s eating all the sweeties? I do not know. Visitors are always offered a plate of snacks. Some of them must find their way onto visitor’s plates. But they’re certainly producing an awful lot of sweeties in the Rashtrapati Bhavan.

enthu: So all this is made in the basement and then brought up to the dining hall?

LC: The banquet hall, yes.

The kitchens are still in the place where they were when the palace was designed. So obviously, they’re in the basement. That’s how it worked in upper-class British houses, and Buckingham Palace, where the kitchens were put in the basement to prevent noise and smell from reaching the residents of the house.

And these kitchens in the Rashtrapati Bhavan really have only just been renovated — I think President Abdul Kalam renovated them during his term (that lasted between 2002-2007). So the staff have only been working in modern kitchens with piped gas with modern rice and lentil grinders for a short time. Before that, they were kind of, I think, grinding the spices by hand, or buying them perhaps. It must have been hot, too. Now, there’s air conditioning!

Also it takes a long time to bring the food up to the table where the president is entertaining his guests. So some of this food is bound to get cold — there are hot ovens in the butler’s pantry next to the banqueting hall to keep it warm. And there is a tandoor there, as well.

enthu: And what is a typical banquet like?

LC: Well like I said, I didn’t eat too many banquets. But it’s a solemn gathering really. Full of protocol – as during the British regime and still the protocol at British state banquets. The president sets the pace, and when he stops eating the plates are cleared. You know that thing about Queen Victoria and how no one would get to eat much because she wolfed down her food? Yes, so all that’s still the protocol that is followed.

I always think — why didn’t India reject this lofty etiquette? Why would you replicate that from the colonial regime for somebody who isn’t even a hereditary monarch?

enthu: And menus, how are those curated?

LC: I think, you know, about a month before a delegation arrives, there’s all these bits of paper swapped detailing food preferences and such. And they do go to quite a lot of effort to make sure that they serve the guests something that they will like. But there’s also certain general guidelines – if they have Westerners, they’ll make the food a bit bland and non-spicy, but when they had the Sri Lankan President, they’d go all out with the spice. So they make quite some effort with food-centric diplomacy.

And the menu is always four courses – there’s always soup, a fish course, a main course, and a dessert. At the beginning the menu was European — like fried fish in tartar sauce, then duck in a mustard sauce, or something supposedly French. I always thought that was a shame. This was the menu when in the 1950s they entertained the Indonesian President Sukarno – the first president of an independent Indonesia, dining with the first president of an independent India. Both nations have incredible food. And what did they eat? Spinach soup.

enthu: That is funny. Would you think that? Like a new Indian nation-state, free from the British regime, but then pretending to be, you know… British?

LC: I mean, yes. But also fine, it’s important to remember that they (India) inherited I think the entire Rashtrapati Bhavan household. So Mr. Rajagopalachari, the first Indian resident of this massive palace, just got things handed down to him – lock, stock, and barrel from Mountbatten who was, after all, one of the most preening, glamour-obsessed people. So the household staff followed the protocol set by Mountbatten. And Rajagopalachari was sort of coerced into a particular pattern of behaviour by the expectations of the staff around him. And I think the other thing is that India also wanted to prove that it was now a player on the international stage. They were hosting people and demonstrating their power. And at the time diplomatic culinary language is some version of French food, so they stick with that, right?

But I must point out that the Ghanaians for example, didn’t do that – when they achieved independence in the 1960s they started serving Ghanaian food straight out.

enthu: Any particular recipes you remember from your time there?

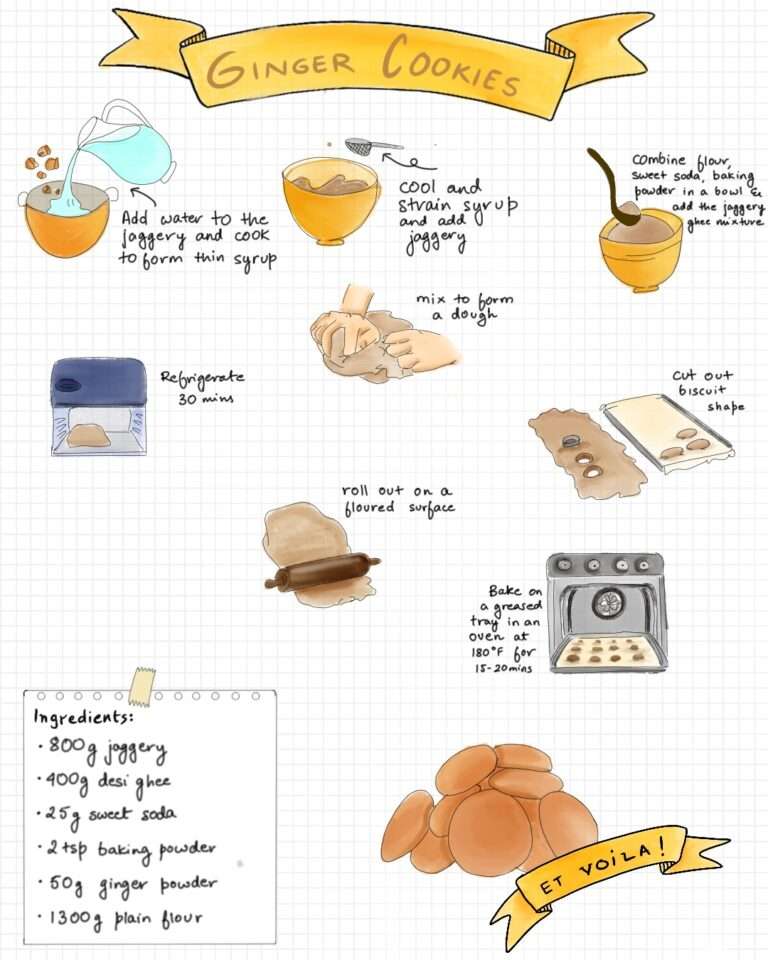

LC: The tea snacks were fabulous. Little idlis and tiny cutlets with chutney, samosas. And they made a constant supply of English-style ginger biscuits that were great. They had a fiery Indian twist. The chef made them with jaggery, which made them even better.