There’s more than enough literature on hot sauce to go around. From archeological studies to scientific analyses, anything you could ever (not) want to know about it is within your reach. My approach has always come from a very practical perspective — to craft delicious condiments that make eating more pleasurable.

I won’t intimidate you with fancy terminology — not that knowledge isn’t a good thing. I want you to get in the kitchen and start making hot sauces of your own. Lots of them. So, no, you will not hear me talking about Scoville Heat Units and capsaicin glands. (The book On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee is an excellent resource if you want to geek out.) Instead, I’ll give you just enough information, gleaned from 20 plus years in the kitchen, to give you what you need to eat well for the rest of your days.

What is Hot Sauce?

For the purpose of this guide, all spicy condiments are hereby deemed hot sauce. Whether thick or thin, chunky or smooth; regardless of texture, viscosity, appearance, or function; if it celebrates the mighty chilli and is not a dish in its own right, we are going to call it a hot sauce.

Often, you will see hot sauces divided into subcategories: fermented, vinegar-based, cooked, pureed, mashes or pastes, and salsas. But any attempts to classify by technique or method alone become useless when considering that many hot sauces often employ more than one. Take for example fermented hot sauces: the fermentation process is typically arrested with vinegar. Does that make it vinegar-based or fermented? Then there are paste-type hot sauces: yuzu kosho, for example, an addictively spicy and citrusy condiment from Japan, is pounded into a paste and fermented to develop a complex flavor. Is it fermented or is it a paste? And what about salsa? Salsa just means sauce in Spanish, so you can see how that would be tough to put a label on.

All I mean to say is that we have a lot of work to do in the world of Hot Sauce Classification, and fortunately, that is not my job. What is my job is to provide you with helpful, useful, and digestible information that can transform your cooking at home.

But Wait, What is Hot Sauce?

Ok, ok. So, you want to know more? Here’s the gist. At some point, someone, somewhere, made hot sauce for the first time, and they did so most certainly by accident.

One can eat only so many fresh chillies, you see, and the plant doesn’t simply stop fruiting when the human is satisfied. The leftovers can be dried, sure, but sometimes they are simply too ripe, having been harvested at the peak of summer, and they begin to rot.

But strange and beautiful things can happen when microorganisms get involved and inevitably that someone must have thought, “hey, let me eat this bubbling, rotting thing and see what it tastes like”. Of course, it may not have tasted as refined as Sriracha does today, but it was a worthy start, and hot sauce was born. Upon further accidents and experiments, it was most likely discovered that those microorganisms produced byproducts that not only made the rotting chilli juices taste better, but also had a preserving effect that made the chillies safe to eat far beyond their expiration date.

In this light, it would be safe to argue that hot sauce is, at its most basic, a preserved chilli condiment (but not always… more on that later).

Note: Over time, we have stumbled upon many of our greatest culinary treasures in much the same way – by developing a taste for rotten food and learning to regulate the microbes involved in the process.

For a complete guide to the basic building blocks of hot sauce, chillies, look at my chilli primer here.

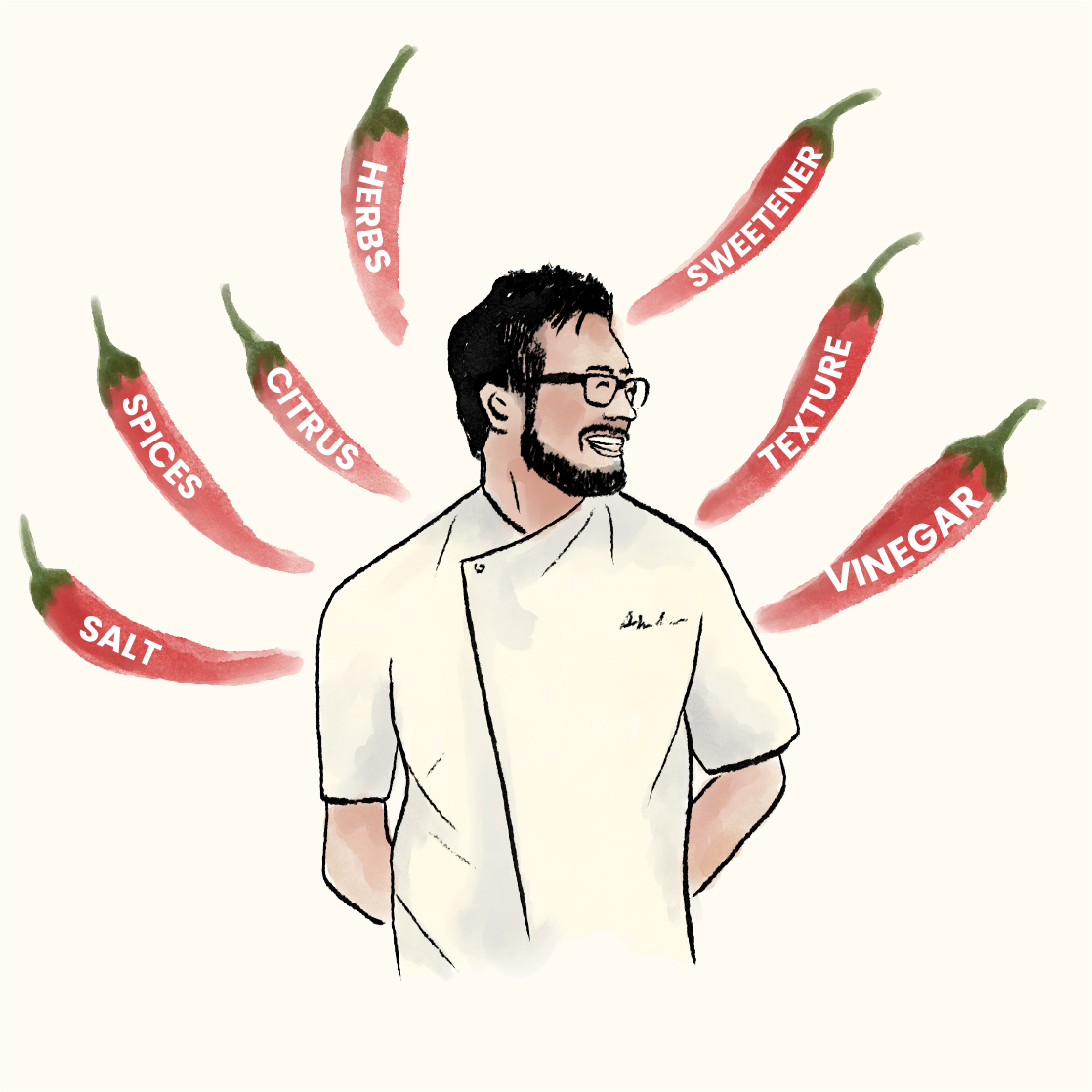

Beyond Heat: Everything but Chillies

Salt

Chillies, alone, don’t make for a very interesting hot sauce.

Salt is the key to turning those chillies into magic. Salt is the ingredient that makes safe and delicious lacto-fermentation possible. From the early beginnings of civilisation, salt has been essential to the preservation of our food and, quite possibly, our species.

Today, we may rely on it less for survival, but it is the single most important ingredient in our cooking: it enhances flavour, allowing us to taste our ingredients at full volume.

In unfermented hot sauces, salt is used to counter the harsh acidity of vinegar and balance the taste.

To illustrate that point, take for example a Japanese ponzu sauce: at its simplest, it is a sauce composed of equal parts sour (vinegar, citrus) and salty (soy sauce). A spoonful of lemon juice on its own would be too intense, as would a spoonful of soy sauce. But, in equal parts, the balanced concoction is addictively satisfying. Acid and salt not only balance each other out, they make each other better. Whether salt is used for fermenting or not, your hot sauce is not hot sauce without salt.

A note on types of salt: Not all salts are created equal, but they are also not that different from one another. It is important to note that they range in densities, meaning that a teaspoon of table salt will have a different weight than a teaspoon of fleur de sel or Maldon sea salt. When fermenting, it is useful to measure your salt by weight (I prefer grams) rather than by volume. And when choosing a salt, I suggest using whatever you have lying around at home, one that you prefer using in your cooking. Table salt (iodised salt) is perfectly fine to use, regardless of what other people tell you.

Acid

Acid, or sourness, is one of the defining characteristics of a good hot sauce, that lip-smacking tang that enhances the flavour of both the hot sauce, and the food it is served on.

I never used to understand why so many classic recipes called for a dash of Tabasco, until I realised that, unlike a sprinkling of black or white pepper, the hot sauce had both spice and acidity, a powerful flavour-boosting combination.

As I’ve mentioned earlier, hot sauce most probably came about at a time when food preservation was essential, and high levels of acid would have been most inhospitable to harmful bacteria and other nasty microorganisms. That taste — the taste of preservation — is so ingrained in the tradition of hot sauce that it would be incomplete without a healthy dose of acid (no, not that acid).

Here are some kinds of acid used in hot sauce:

1. Lactic Acid

Lacto-fermentation has become a catchphrase in the post-Noma era, but it’s not as technical as it might sound. Lactic acid is what makes naturally fermented foods possible (think: sauerkraut, kimchi, paniwala achaar in India). Naturally present bacteria eat up the sugars in the food and expel waste in the form of lactic acid. As the lactic acid builds up, it lowers the pH of the environment until it reaches the point at which harmful microbes can no longer survive. In culinary terms, it makes the food sour and delicious.

In the context of making hot sauce, this lactic acid is introduced by either blending naturally fermented chillies into a puree, or by straining and pressing out the sour fermented chilli juice. For my taste, fermented chillies ripe with lactic acid will yield the tastiest type of hot sauce. Just keep in mind that it takes time (think: days, weeks, months).

2. Vinegar

One of the most common ingredients in hot sauce, aside from chilli, is vinegar. Vinegar is an indispensable tool in your pantry and one that serves a number of purposes when it comes to making your own hot sauce at home. If you, like me, are filled with anxiety at the sight of an empty bottle of Cholula or Tapatio, you have vinegar to thank for that. Many of the Mexican or Mexican-style hot sauces rely on vinegar for their signature zing, as they are rarely fermented and need acid from an outside source. If you find yourself making a fermented hot sauce, vinegar can be used to lower the pH levels enough to prevent further fermentation, allowing you to achieve the desired flavour profile with precision. (It is also a safer approach to fermentation and one that I ascribe to). We call this “arresting the fermentation”, very fancy.

Vinegar is most useful to the novice hot sauce enthusiast. If you’re just getting started and want to be successful on your first attempt, I strongly recommend you try a simple (though no less delicious) blend of chillies, vinegar, and salt. Put it in a jar and let it age in your refrigerator, it only gets better with time.

3. Citrus

It would be hard to imagine pico de gallo, nam jim, or spicy green chutney without the punch of freshly squeezed lime juice. Lemons, limes, oranges, even grapefruit, all are fair game when it comes to hot sauce. Citrus is best used when enjoyed fresh, rather than in a preserved application, as the juices tend to break down quickly and develop unpleasant, bitter flavours.

Flavourings

Whether attempting fermentation or sticking to a straightforward blend of chillies, vinegar, and salt, you would be remiss not to consider the potential flavourings that exist all around you. The addition of even a few cloves of garlic will dramatically change your hot sauce, especially when thrown in with the chillies during fermentation.

Cooking methods, too, are at your disposal. I particularly love the character of a hot sauce made with fire-roasted chillies. My addictive recipe for smoky tomato salsa blends burnt chillies and tomatoes with chipotles in adobo for a double smoky, double delicious sauce. Whatever you choose to incorporate into your hot sauce, the sky’s the limit.

1. Fruits

An excellent way to mellow out the intense spice of a hot chilli is to temper it with fruit. We don’t often think of tomatoes as fruits, but they are a common addition to hot sauce and yield great results. Tomatillos, green tomato-like relatives of the gooseberry, are essential in making fresh salsa verde. If attempting to make a hot sauce with habanero chillies, a few fresh peaches or mangoes will work wonders in bringing out the natural fruity characteristic of the chillies, while also making it palatable. Berries are fantastic, too. When considering which fruit to use, I like to match them to the colour and flavour of the chilli so as to preserve and enhance the chilli’s innate qualities, rather than mask them.

2. Vegetables

Like fruits, vegetables add body to a sauce and mellow out the spice. Of course, they will also add a flavour of their own and in some cases, like garlic, they may only need to be used sparingly. Onions, garlic, and ginger are perfect for laying a foundation of flavour and adding depth to the sauce. Carrots work well in purees, not only because of their smooth texture when blended, but also their stunningly bright orange color. Bell peppers are an excellent resource when you want to tone down the spice of the chilli without adding too many other flavours into the mix; their flesh tastes similar to that of the chilli minus the heat.

3. Spices

When I think of Jamaican jerk sauce, I immediately sense the heady aroma of allspice. Cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, black pepper, cardamom, all are commonly found in the pungent pepper pastes and sauces of North Africa and The Levant. Toasted cumin adds a unique depth to both Mexican-style hot sauces and Indian chutneys. The trick to using spices is to use them in moderation, as their flavours can quickly overpower the sauce if you’re not careful.

4. Herbs

Green chillies and herbs have a natural affinity for each other. Salsa verde, pico de gallo, and green chutney, all are brought to life by the unique flavour and freshness of cilantro (fresh coriander leaves and stems). Oregano, both in its fresh and dried forms, lends an earthy, vegetal quality for which there is no substitute. Aromatic Thai basil and makrut lime leaves will take your hot sauce to the next level, though best when added whole, allowed to infuse, and removed before serving.

5. Sweeteners

Spicy loves sweet. Unlike the other tastes, sweetness has a soothing effect that makes eating spicy food more enjoyable. It’s like an ice-cold cola after a spicy biryani — few things are more satisfying. Nam jim, an intoxicating Thai dipping sauce, would be much too pungent without palm sugar to help bring it into focus. And then there’s Sriracha, everyone’s favourite hot sauce. Take a look at the back of the bottle of Rooster brand Sriracha and you’ll notice that the sauce is full of sugar, second only to chillies. Whether using sweetness to balance out your hot sauce, or as a primary characteristic, it’s always best to start with less and add a little at a time, tasting as you go.

Texture & Consistency

There is a near limitless array of hot sauces in existence, both obscure and commercially available, and, therefore, an infinite number of textural possibilities when crafting your own. More often than not, the consistency will be determined by the intended use. If you want to make an all-purpose hot sauce, perfect for splashing over everything on your plate, thinner is better. On the other hand, if you’re a big dipper and want to scoop some spicy goodness onto your tortilla chips or freshly baked flatbread, err on the thicker side. Pastes, because of their concentrated flavour, are best when added to soups, sauces, and curries, or in situations where you want small but intense bursts of flavour (like, say, eating Kobe beef with yuzu kosho). Don’t get too caught up in deciding the texture before you start cooking. Just follow recipes you like, adjust as you see fit, and remember that if it’s too thick you can always thin it down with water (or more hot sauce).

Chef Alex’s Hot Sauce Recipes:

Hot sauce comes in hordes of styles: cooked, raw, fresh, fermented, thick, thin, chunky, smooth. Chef Alex shares recipes for five of his favourite ones.

- Fermented Chillies

Note: Dear Reader, before attempting this recipe be sure to read the guide to chilli fermentation so as to do this as successfully and, most importantly, as safely as possible.

Ingredients:

2.25 kg water

110 g salt

1 kg Bhavnagri chillies, stems removed

30 g garlic

Method:

- Bring the salt and water to a boil to dissolve the salt evenly in the water, creating a brine. Allow to cool to room temperature.

- Slice all the chillies more or less the same size. Add the chillies and garlic to a sterilised, non-reactive container or jar and cover with brine liquid.

- Ensure that all of the chillies are completely submerged in the liquid by placing a sheet of plastic wrap and a weight on top of them. A ziplock bag filled with water also works very well.

- Allow the chillies to ferment at room temperature for about five to seven days, changing the plastic wrap every 24 hours, and skimming off any white yeast that collects on the surface.

- Taste the chillies and the brine every day. You will notice that they go from raw and salty, to tender and sour. When you are happy with the taste and they have become pleasantly sour, they can be stored in the refrigerator until you are ready to make your hot sauce.

2. Fermented Chilli Hot Sauce

Ingredients:

500 g fermented Bhavnagri chilli and garlic

250 g fermented chilli brine

0.5 g xanthan gum (see note*)

16 g sugar

50 g white distilled vinegar

Salt to taste

Method:

- Strain the chillies and garlic and save the brine.

- In a high-speed blender, blend the chillies with brine until smooth. Add xanthan gum and blend further until lightly thickened.

- Pass the hot sauce through a fine sieve and season with sugar, salt, and vinegar. If you find the hot sauce too thick, a little filtered water can be added to loosen it up.

Note: The xanthan gum is not required, but it will add body to the finished sauce and will help keep the sauce from separating as it sits.

3. Fresh Tomato Salsa

Ingredients:

500 g Roma tomatoes, whole

100 g red onions, peeled

50 g green chilli, stem removed

25 g coriander, washed, hard stems removed (delicate stem is delicious)

Lime juice, to taste

Salt to taste

Method:

- Make a thin slice across the tomatoes to remove the core and create a straight and flat surface of exposed tomato flesh.

- Using the large holes of a cheese grater, grate the tomatoes into a bowl, stopping once you reach the skin. The skin can be discarded. Season the grated tomato with a few pinches of salt and stir to incorporate.

- Finely chop all the onions, chillies, and coriander leaves. Add the chopped ingredients into the mixing bowl with the grated tomato. Add another pinch of salt, stir, and cover the mixing bowl with cling film.

- Place the mixing bowl in the refrigerator and let the ingredients meld for at least three hours and no more than 12 hours.

- Right before serving, add lime juice to your taste and season with more salt if needed.

Note: Adequate seasoning (salt and lime juice) will make all the difference between a dud and a superstar. Don’t be afraid to push the limits on seasoning, adding a little salt and lime juice as you go and tasting along the way until you are satisfied. The salsa should make you want to dance when you eat it.

4. Salsa Negra

Ingredients:

200 ml vegetable oil

20 g chiles de árbol, stemmed

25 g guajillo chillies (about 3 chillies), stemmed, seeded, and cut into pieces

10 black garlic cloves, peeled, minced

10 fresh garlic cloves, peeled, minced

1 tbsp white wine vinegar

1 tbsp brown Sugar

¾ tsp cumin seeds

¼ tsp salt

Method

- In a large saucepan, combine the oil and the chillies and cook over moderate heat, stirring frequently, until fragrant and the chillies are browned in spots, about seven minutes. Remove from the heat and stir in both garlics along with the vinegar, sugar, cumin and salt. Cover and let cool.

- Transfer the chilli mixture to a blender and pulse until a coarse paste forms. Season with salt if necessary

5. Habanero Hot Sauce

Ingredients:

145 g white onion

65 g carrot

40 g fennel

20 g garlic

300 g habanero chillies

45 ml apple cider vinegar

0.5 g xanthan gum (see note*)

Salt to taste

Method:

- Preheat an oven to 200 degrees celsius.

- Lay the habaneros out on a large baking tray and cook until black and charred on all sides.

- Place a saucepan over moderate heat.

- Slice the vegetable aromatics (but not the chillies), and cook them in a small amount of neutral cooking oil until softened, stirring occasionally. About eight to ten minutes.

- Add the charred habaneros to the saucepan, and continue cooking for a minute or two until the blackened skin starts to break off into the vegetables.

- Add enough water to barely cover the chillies and vegetables, bring to a simmer. Remove from the heat and allow to cool to room temperature.

- Using a high-speed blender, blend the mixture until smooth, then add the xanthan and blend further until lightly thickened

- Strain the hot sauce through a fine sieve and season with salt and apple cider vinegar.

Note: The xanthan gum is not required, but it will add body to the finished sauce, and will help keep the sauce from separating as it sits.

This is part two of our three part Hot Sauce series curated by Chef Alex Sanchez. Read the first part here.