Nearly twenty years ago, filmmaker Mira Nair wrote a really fun story about how on-set snacks scaffold her movie-making process.

INTRO

On enthucutlet’s wishlist for our filmy season was a story by the celebrated filmmaker Mira Nair. She wrote this story for the November 14, 2004 edition of The New York Times, and has generously shared it with us. Many of the movies she writes about here went on to become iconic pieces of cinema, and so this story makes a glorious throwback.

I cannot think without chai. And I don’t mean the corporatized chai that comes in a packet. I mean the made-from-scratch variety that I make every morning, whether I am shooting a film or cooking breakfast with my family.

Chai is what I discovered on the railway platforms of Bombay while making my first film, “Salaam Bombay!” Hot, sweet matka chai served in famously biodegradable clay cups – to be tossed nonchalantly onto the train tracks when finished. It was this brew that I got hooked on to combat the moment of exquisite terror I felt each morning making my first film – of worrying where to place my camera as a hundred-odd crew members awaited my next instruction; how to think clearly as I controlled the surging crowds that got in the way of the street children in front of my lens; how to gently tease a knowing smile from a non actor while eliminating the swagger of a film star.

A director’s day is a pyramid of details: a hundred questions need to be answered, so many flowers to be coaxed into bloom.

To make chai, I use a special pateela, or copper-and-steel pan, that is reserved for tea and nothing else: first, using my teeth, I break open 5 to 10 cardamom pods — the black fragrant seeds bouncing on the shiny stainless steel is often the day’s first image. Then I add freshly chopped ginger, still encased in its skin, immersing both in many cups of boiling water. After a few minutes, in an act of surrender to New York living (ignoring the Lipton Green Label tea my mother brings with her each time from Delhi), I put in three bags of Twinings’ English Breakfast tea, gradually letting the brew turn a solid mahogany red.

Only after the brew is solidly steeped do I pour in some whole milk — andaaz sey, as my mother would say, that is, a loving approximate, without measuring cups. As the tea, now milky, erupts into a foamy mass, I remove the tea bags with a wooden spoon, the spartan in me pressing each one empty of cooked tea before throwing it away. Finally, the tea is poured through a sieve into a flask for keeping warm. This process, call it a meditation, takes at least 15 minutes – 15 minutes of nonmultitasking – when the tea is, as it were, marinated in love. Chai-making, like cinema, is all about rhythm, patience, and timing.

With every film I make, I find one food crutch to sustain me through the battle. A director’s day is a pyramid of details: a hundred questions need to be answered, so many flowers to be coaxed into bloom. And yet a director must also preserve clarity and space so that instinct can reign. Who needs to add another decision of what to eat to this? So I fixate on one satisfying food that’s around, usually something local and hearty, and order it day after day, refusing to add another choice, another decision, to the mountain of the day.

When making “Mississippi Masala” in Greenwood, it was catfish. With “Kama Sutra,” it was, absurdly enough, a combination of chicken kathi rolls and an open-faced tuna fish sandwich served up in the Holiday Inn in Jaipur. With “Monsoon Wedding,” it was my mother’s cooking that nourished the cast and crew daily. With “Vanity Fair,” which was filmed in London, it was, lethally, baked beans over fried toast, because this rang a childhood bell, recalling a snack from the colonial Gymkhana Club in Delhi where I taught myself to swim decades ago.

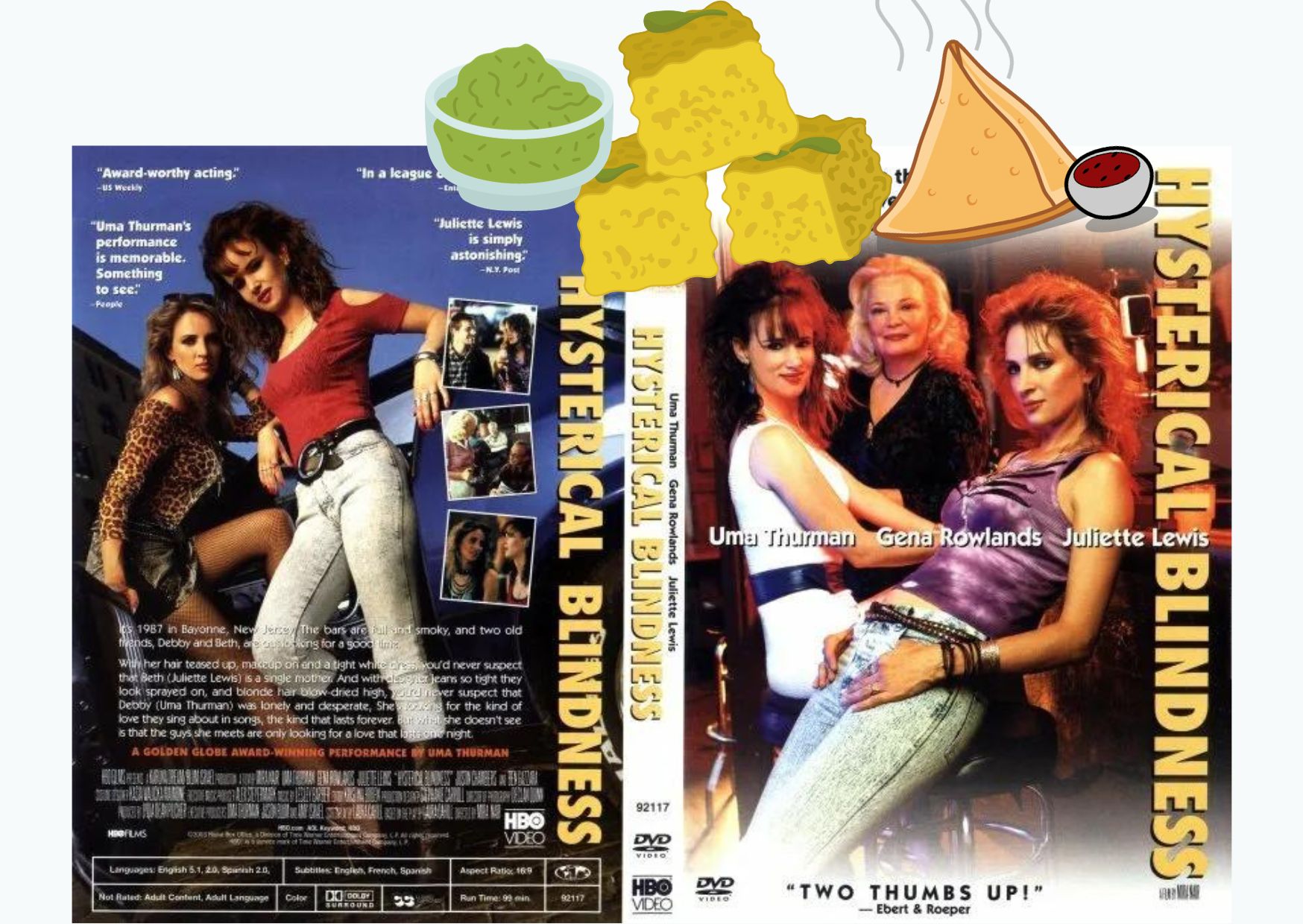

In the summer of 2001, my pal Uma Thurman persuaded me to direct her in “Hysterical Blindness,” a slice of 1980’s Americana. Fueled by John Cassavetes’s portraits of dented souls in urban America, I began to prowl the streets of New Jersey looking for bleak industrial landscapes and an interesting bar. We finally settled on Bayonne, a little town just across the river from New York, distinctive in my eyes because of the many bridges that lead into it. I thought the visual motif of the bridges would be an excellent metaphor for Debby Miller, Uma’s character, a loveless navel-gazer who would work herself up to a state of temporary blindness in her ceaseless quest to find a new man in the depressingly limited gene pool of her one-bar town. I put the bridges in the background of many shots to show how Debby never looked outside her own tiny world.

As the crew began to light the set, I found myself at a craft-services truck on a street in Bayonne teaching my new assistant how to make chai. But we had no fresh ginger. Impulsively, we hopped into a car and drove past strip malls, delis, and corner groceries, looking for ginger — but not one person off the New Jersey Turnpike seemed to know what it was. Suddenly we arrived in Jersey City, and as we descended onto Newark Avenue, I felt as if I were back in Chandni Chowk, Old Delhi. Higgledy-piggledy neon signs (Roopali Jewelers, Patel’s Video, Baba Hut Buffet) broke the bland cityscape, sari-clad Gujarati ladies crossed the street carrying large bunches of fresh coriander and next to gaudy posters screaming “Shahrukh Khan at Nassau Coliseum” were stacks of wooden crates filled with garlic and ginger, sunning on the sidewalk.

Uma would sidle over to me in her ripped Joan Jett T-shirt and blue eye shadow to ask, “Is it samosa time yet?”

By 11:15 a.m. on the set, the craft-services trays would be circulated among the crew. Krispy Kreme doughnuts, mountains of overbright candy, and bagels slathered with cream cheese would be shoveled into the mouths of a crew on autopilot — give me something, anything, a sugar rush, a caffeine fix, to get through this day. Granted, I was filming Americana, but surely Cassavetes would not have insisted on eating American food to make an American film.

And Americana now included Newark Avenue, too, so I indulged in a bit of director-as-goddess and sent my assistant out to look for the steamed and fried vegetarian snacks characteristic of the Gujarati community that had made Jersey City their capital for the past 30 years — the pet-puja, or food that would sustain me. And sure enough, from Rajbhog Sweets and Snacks, a small storefront, came fresh kachoris, samosas, gathias, and chutneys made that day. A small tray would make its way through the Bayonne bar set, past dozens of Madonna look-alike extras in spandex and shoulder pads. As others tucked into Krispy Kremes, I’d pop the just-made almond kachori in my mouth, no cutlery needed, licking the sour-sweet taste of tamarind chutney off my fingers. The next day it would be samosas or khandvi or steamed dhokla — and each day after, instead of being worn out by the suburban angst I was filming, I felt clean and refreshed.