While Shirin was writing this story, enthucutlet reached out (with fingers crossed) to Pallavi Nirula Nath. Pallavi is Mr. Lalit Nirula’s daughter, and an entrepreneur in the primary education space. With her father, they mined their albums for archival photographs of the family’s restaurants. The posters and photos they found, and generously shared with us, are such treasures that we decided to make them into a photo essay.

So we went back to Mr. Nirula, and asked him to share his notes on each of these never-seen-before images. Even for folks who have never been to Nirula’s or Chinese Room, these stories are a rollicking trip down decades of Indian dining.

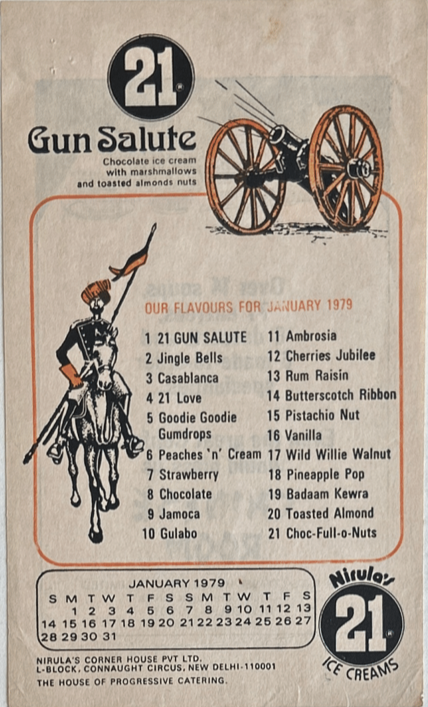

Nirula’s printed a calendar every year with the flier for each month showcasing one flavour. “Every month, we came out with a new flyer and an ice cream; we put the month up in the front, and the back of the sheet had the list of ice creams and our locations,” says Mr. Lalit Nirula. “This one is from our Republic Day project. On the 26th of January every year there is a huge parade in Delhi and we put that on our calendar.”

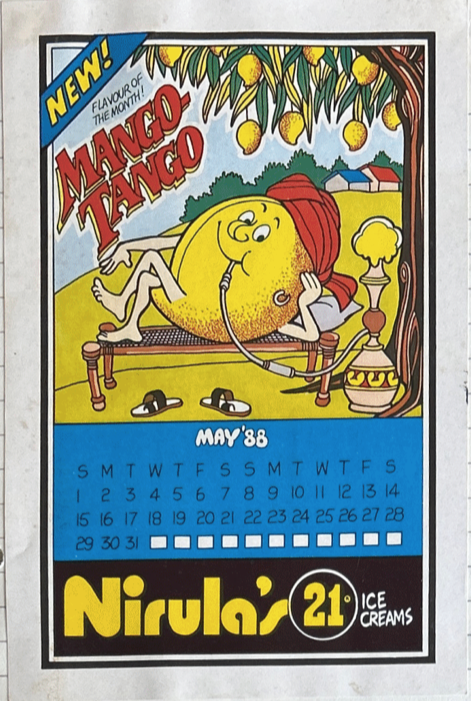

Nirula’s offered mango ice cream only in season. And it wasn’t only just one mango through the season. “In April we got Alphonso from Mumbai,” says Mr. Nirula. “Later in the season we got Dussehri from Lucknow, and in August, we would finish the season with Chausa from Delhi.”

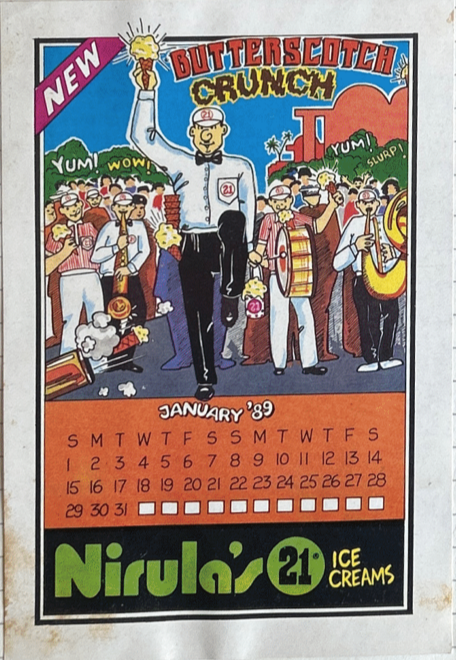

“We had 16 to 17 steady flavours and about five to six kept changing through the year,” says Mr. Nirula. “The hope was that someone would keep our fliers on their table with the flavours visible. This is another one from our Republic Day project.” Mr. Nirula’s daughter Pallavi, like the rest of us, thought that Nirula’s 21 Love came from the brand’s 21 flavours and the affection associated with them. “21 Love was introduced during the Davis Cup matches in Delhi,” says Mr. Nirula. “It is a tennis reference.”

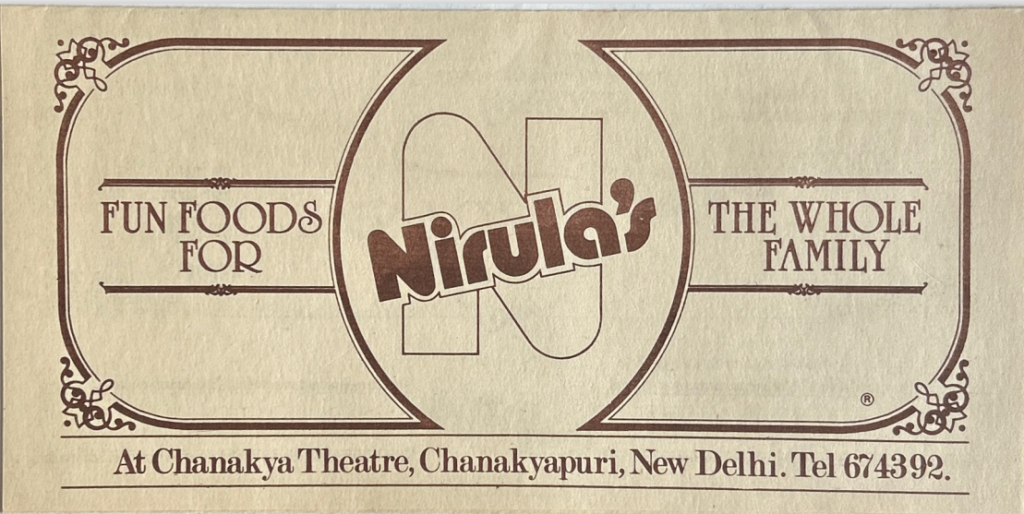

“This is the Chanakya Cinema restaurant,” says Mr. Nirula. “It was on the ground floor of the building, which was a classic cinema building of those days, a good architect had designed it. We didn’t want people to come to a plastic dining situation. This restaurant had a lot of greenery and plants, and these bamboo chairs. The restaurant also overlooked a pond and Chanakya fountain, which never worked. It was very popular with the convent school nearby, lots of schoolgirls would come to this restaurant.”

The fans we see in the image go back a long way with the Nirula family. “These are old fans with two wooden blades,” says Mr. Nirula. “We picked up from the boarding school my brothers and I went to in Dehradun. They’re very expensive to run. We told the school that we would give them free new ones, if they gave us these old ones. We had to change the motors in them before we installed the fans. We used these fans in Chanakya and in Connaught Place. This was in 1981 or ‘82.”

“Mr. Chang designed this revolving door for us, and it was done entirely in-house. It was the first of its kind in India. We don’t see anything of its kind any more.” – Mr. Nirula

“We got this Laughing Buddha statue for the Chinese Room from Bombay,” says Mr. Nirula. “Lots of kids would come and rub its belly. The crockery in the foreground is rice pattern or rice grain crockery from China. We used [this dinnerware] from day one in 1950 until the Chinese Room’s closing.”

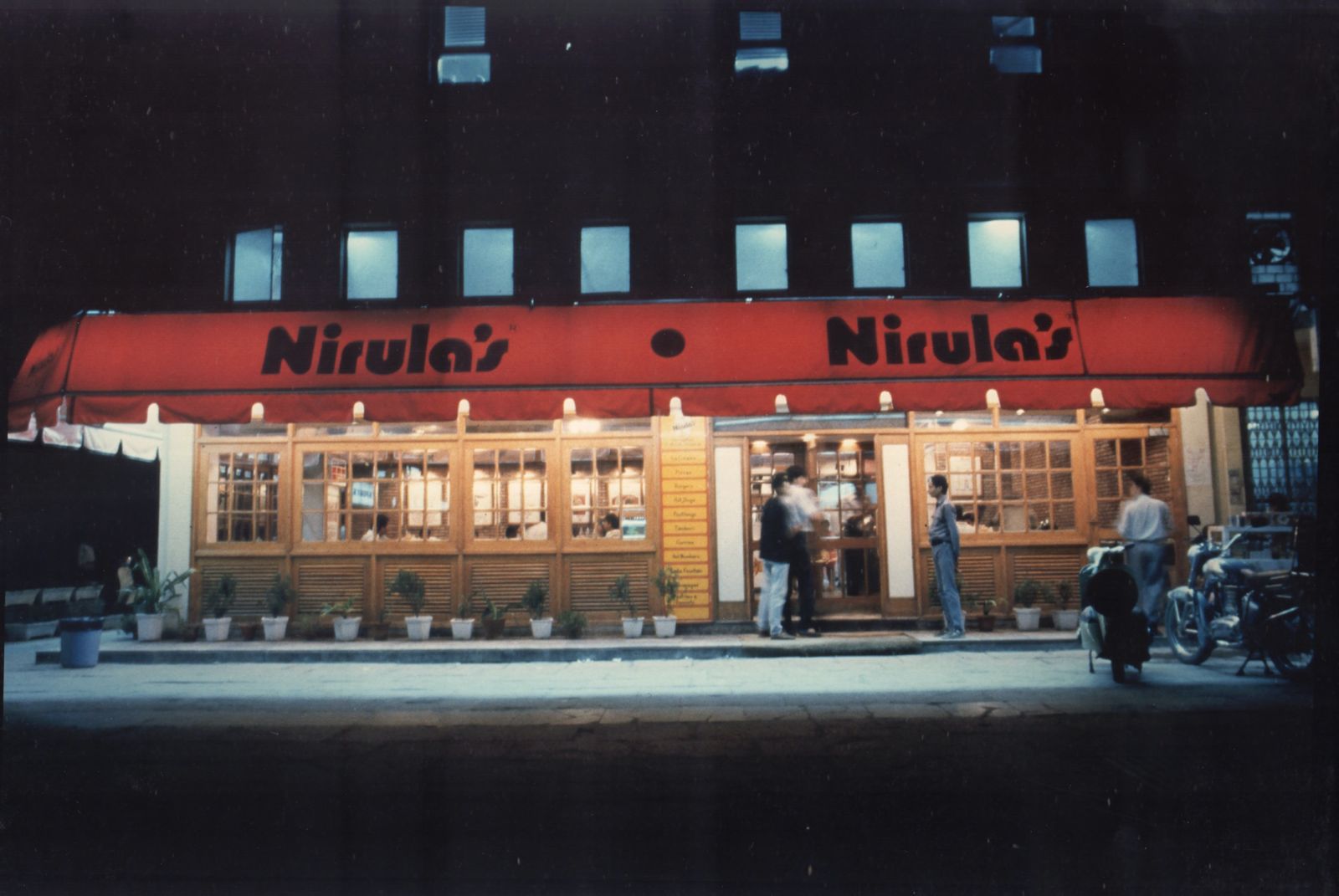

This is one of Nirula’s later FSRs, with standing room in the front and seating at the back.

“Our Defense Colony restaurant was built under a flyover, so we got this height,” says Mr. Nirula about this iconic ceiling. “ We had seen ducts in Hawaii, and we thought it was a very cool idea. We painted them and converted them into a design element for Nirulas. With exposed ducting, you don’t need a false ceiling, and you don’t need to insulate them because the condensation evaporates. It’s cost-saving design.”

“These thick black spiral columns, and the brass railings – everything was made inhouse for Pegasus Bar at Nirula’s Hotel in Noida,” says Mr. Nirula. “We had a poster here which showed the various beers of the world on a map. We’d brought it from the US and it got us into trouble. It showed Kashmir as part of Pakistan, a lawyer complained and we had to deal with a police challan.”

A smaller Nirula’s FSR, in Noida.

“Pot Pourri ran from 7am to 11pm. We had two specials for the day, and a salad bar as our USP, serving prepared salads, like chicken salad, and German potato salad. We thought, if it doesn’t work, we’ll make it into a dessert parlour. The younger generation got it but the older ones had no idea.

But it worked. It was a first in India, one of our many other firsts, like an ice cream parlour, and a coffee shop.

You can also tell from the menu that we wanted to duplicate usage of raw material from other restaurants.”

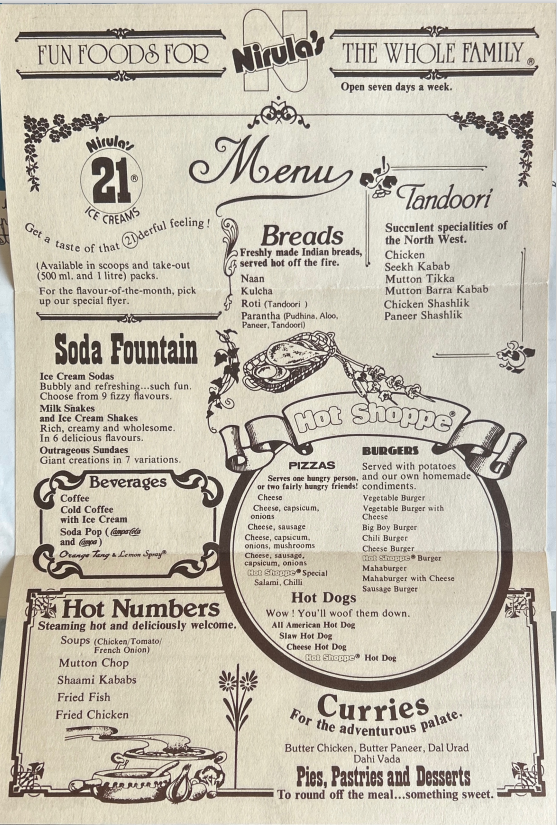

“When kids who were seven or eight visited Nirula’s they wanted burgers and other western food. When they became 22-23 they came back to wanting Indian food. Nirula’s menu had something for all generations.”

“The menu was started and designed by Chinese Room’s first chef Li Wo Po. He had come into India with Chiang Kai-shek, and stayed on and got married to a south Indian lady. It was a very happy marriage because he didn’t speak Tamil, and she didn’t speak Mandarin. Chef Li died on the job, quite literally, in the mid 1960s.

Chinese people order food at restaurants [not by names but] by numbers, so Chinese Room’s menu was by numbers. We had 90 items until the main course. With beverages and dessert, it went to 116.

Our servers at Chinese Room were not literate, but they could take orders for tables of eight people, and sweet talk everyone in the room, asking, ‘aaj kya haal hai bachhon ka?’

Chinese Room ran from 1950 to 2006-7. Once I had five generations of a friend’s family come to the restaurant.”