An Indian cook is defined by the masala dabba they wield, says Rushina Munshaw Ghildiyal.

Masala (spice) + dabba (box) = masala dabba or spice box.

The masala dabba is a mainstay in every Indian kitchen in India. As a concept, the masala dabba is pure genius. Not surprisingly, it has prevailed across centuries, with generations of cooks putting it to the test. So much so, that when Tupperware entered India, a masala dabba was one of its early offerings.

Culinary cultures around the world have developed their own repertoire of signature tools and utensils that most suit them. India, and perhaps south Asia, are unlike any other culinary cultures in their degree, complexity, and frequency of spice usage. It is no wonder then, that these regions have designed specific solutions to optimise their usage of spices effectively. The result of this ingenuity is the masala dabba, a multi-compartment box to keep daily-use spices handy, as well as the tadka vati or kadchi, a small bowl-like receptacle with or without a handle used to temper food.

Then the ladies of our family would get to work; one on each side of the mortar, pounding out a rhythm with the large pestle, singing and gossiping as they went.

I have a very poignant memory of the day I got my first masala dabba. It was just before I was to be married. One day then, my nani took me to the bartanwala our family has patronised for generations with the objective of helping me set up my new kitchen. The masala no dabbo, as it is called in Gujarati, was the first item we ticked off the list. Nani picked one that she felt would be appropriate, and got it engraved with my name. I was euphoric as I carried it home to my mother. Until then, I had watched my grandmothers and my mother begin their daily cooking ritual by lifting the lid of their dabbas.

“Haldar, marcha, rai, jeeru, hing, dhana jeera no masala, taj, ane laving,” checked off my mom in Gujarati as she filled my new box with turmeric, chilli, mustard, asafoetida, coriander-cumin masala, bay leaves and cloves, while listing uses and properties. She followed it with her blessing of “rasoda ni rani banje”, may you become the queen of your kitchen as she shut the lid and handed it over to me. I remembered thinking, that I too would now, (hopefully) open my dabba and create magic with a pinch of this and a sprinkle of that, just like they did.

It was not until much later, when I began researching Indian cuisine, that I wondered why the masala dabba is so intrinsic to our culinary culture. This is when I recalled an annual cycle – one that my dadi followed, and I loved ‘helping’ her with as a child – storing masalas for the year.

In our home I knew it was time for masala production when the spice pounders arrived, with mortars and pestles so huge and massive, that my younger self could sit in them. Over the next few days, they would proceed to process many kilograms of spices. Chillies, coriander seeds, cumin, and dried rhizomes of turmeric would be sun-dried on large plastic sheets in the summer sun. Then the ladies of our family would get to work; one on each side of the mortar, pounding out a rhythm with the large pestle, singing and gossiping as they went.

The output of all this industry was stored in large aluminium boxes in the kothar (storeroom) along with staples, and other dried and preserved produce. Most of India followed similar cycles of processing spices in high summer, and storing them for use year-round. India’s tropical climate makes food and ingredients susceptible to microbial interventions. Spices with high quantities of essential oils are especially susceptible to exposure from air, heat and humidity, and can lose potency, or spoil easily. Spoilage and oxidation is more likely after they have been powdered. The masala dabba allowed for small quantities of spices to be kept handy near the cooking area, whilst keeping the bulk safe from unnecessary exposure. So much so, my dadi kept the more exotic, expensive spices locked up in her cupboard, which resulted in an interesting side-effect. Her sarees were infused with their aromas.

I have come a long way from my first masala dabba. Over time, my fascination for them has grown, and I now have a collection of beautiful dabbas. I have inherited my nani’s beautiful large brass dabba, and several of her wooden ones. I have learned that masala dabbas come in a variety of materials, shapes and configurations, fashioned from wood and metal, in functional round, square, ornate and fanciful shapes, and they can have various numbers of compartments.

A masala dabba becomes an extension of its cook, reflecting region, cuisine, and individual proclivities.

Many parts of India traditionally used wooden dabbas that were easier and more optimal to form into squares. Because these divide best in squares of two or three, they would be divided into four or nine compartments. With the advent of metal, round shapes became more prevalent because metal is easier to mould into round shapes. The round, steel, or plastic masala dabba is the most commonly available one today, typically with five to seven katoris within it.

There are two masala dabbas I have coveted ever since I heard about them. The first is the anjarai petti of Tamil Nadu – a large wooden spice chest that comes with two storeys. The second is Kerala’s Mappila masala peti, a two-feet-high spice box that functions as a stool for the cook to sit on in the kitchen.

The masala dabba is not only about the box. It is also about what it contains. When I first opened the masala dabba in my mother-in-law Saroj Ghildiyal’s Garhwali kitchen, I had an epiphany. Ma’s box was an indication of just how different the food of my new home was from the Gujarati kitchen I grew up in. While there were some familiar spices, many such as jakhiya (dog mustard) and jambu (allium stracheyi) I had never seen before. Over those next few weeks, while watching Ma cook from her box, I learned about these unusual spices, and also realised that she was an encyclopaedia on spices, and tahseer (the effect of an ingredient on the body). She chose spice and ingredient combinations based on this tahseer, a philosophy that optimised the nutritional quotient of her cooking.

Almost every home in India has a masala dabba. However, the traditions around these nifty containers change from region to region, and from cook to cook. They differ in their local names, the materials used to make them, the configuration of their compartments, and the contents of those katoris.

Cooking goes beyond the act of converting raw ingredients into cooked food. Everyday cooking is art and science, and Indian cooks wield their masala dabbas like artists use their palettes, to layer flavour into their dishes and to ensure the combinations deliver maximum benefits to the body. A masala dabba becomes an extension of its cook, reflecting region, cuisine, and individual proclivities. It plays multiple roles of tastemaker and flavour enhancer, as well as a home apothecary used to prevent illness, and to enhance functional nutrition in the family’s diet.

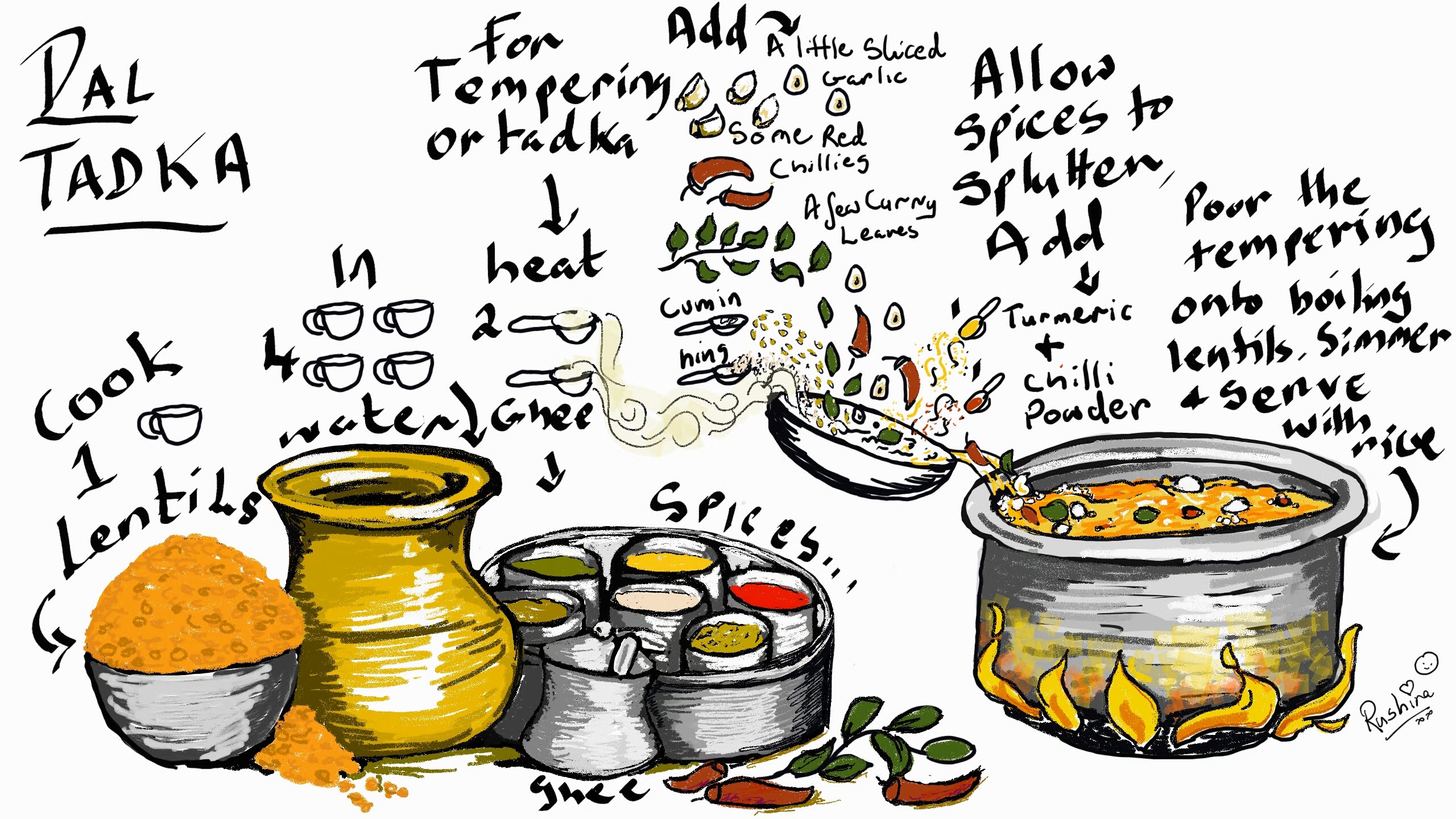

Using the masala dabba, Indian cooks create complex layers of spices in their cooking. They begin with a tadka (or tempering), using whole seed spices like cumin or mustard, followed by fresh spices like green chillies, curry leaves, garlic, and onion. This is followed by the central ingredients, and then by powdered spices or masala blends. When the dish is almost done, souring agents like kokum, anardana or dried mango are added. At the very end, there may be additional finishing spices, or a finishing tadka, and a garnish of fresh coriander.

Tadka is an intrinsic distinguishing step in Indian cooking, and it is applied either before and/or after most dishes are cooked. An important partner to the masala dabba is the tadka vati or kadchi. This is a small bowl with or without a handle that is used to heat a little oil or ghee. When the fat is hot, small amounts of spices are added to it. Once they are crackling and fragrant, the bowl and its contents are poured onto the dish.

Traditionally tadka vatis were made of iron, or brass, which fortified the nutrient value of the dish. Today, they are made in a variety of metals. Material notwithstanding, the result is an undeniably Indian flavour and aroma that rounds off the dish.

The masala dabba is a pivotal part of the Indian cook’s toolbox. Inside it lies all of the collective wisdom and creativity of the Indian home kitchen. Cooks use their dabbas to create all sorts of spice permutations and combinations, based on available ingredients, the season, and what their family needs at every meal. And so, each masala dabba and its owner offer an endless journey of discovery.