Ice Orathi on Kozhikode’s beaches is a ritual, a memory, an astonishing sensory experience, a taste of the city’s culture.

“Wonderfully weird.” This is how the ice orathi was described by my friend Saina Jayapal, an established PR and brand communication consultant in the F&B industry. She is originally from Kozhikode.

Malabari cuisine, specifically the kind found in Calicut, is world-renowned – from Kozhikode’s halwa and ari kadukka (or fried kallumakkaya aka mussels) off the streets of the city to unakkaya and biryani, which are best eaten in the houses of ever-hospitable locals. Ice orathi however, is vastly different from the typical dishes the city is known for. It is an experience that is closely entwined with Calicut Beach. Known by many names: ice orathi, ice achaar, or churandi ice, this dish is always part of the memories people associate with their time at Calicut beach.

Even visitors who may have chosen to not try the dish take note of the vendors who dot the beach with pull carts, their blocks of solid ice, helmed by glass jars filled with bright pickled vegetables and fruits, and toppings aplenty. While I am yet to experience the joys of ice orathi, for this story, I turned to those who have.

It was a dish that people would ask their friends to try, simply to see how they react to it.

There are many renditions of shaved ice all over the world. For most Indians, the gola is most familiar. But the savoury shaved ice in Calicut is unique in more ways than imagined. According to Beryl Shereshwesky (@shereshe), a New York-based food enthusiast and YouTuber who recently did a video on ‘Shaved Ice From Around The World’, ice orathi is a stand-out star. For a palate that has tried many world cuisines, the first mention of this dish attracted intrigue from her viewers. “Pickled vegetables and briney water over ice? Who wouldn’t be fascinated?”

Beryl says on trying the dish, that the experience of it was “distinct and incomparable”. In speaking with us for this story, she said, “Looking at the category of shaved ice as a whole, you will see the common theme of sweet and fruity mixed with the cooling element of ice. Whether you’re looking at Italian-style granita in the US, bici bici in Turkey, Cambodian tha-kaut chu, or Filipino iskrambol, the flavour profiles are similar, even if the fruits or syrups differ across regions. Ice orathi stands on its own because of how it subverts flavour expectations. It challenges you to think differently about (what I think is) a universal food.”

The information available about ice orathi’s history is murky. While chatting with the aforementioned Calicut-origin friend Saina, we realised that mere speculation is all that we have. She says that there is one thing about this local shaved ice that resonates with everyone: whether they love it, hate it, or are indifferent to it – ice orathi is a simple dish invented from some sort of necessity. “I feel like ice orathi was made with whatever was available,” says Jayapal. “It provided some novelty that appealed to the visitors to the beach. More than its taste, it was an [unusual] experience that would surprise the senses, and [alter] the idea of what an icy treat could be. It was a dish that people would ask their friends to try, simply to see how they react to it.”

The nostalgia associated with the dish is better recorded than its actual history. Aneez Adam, the founder and CEO of Aadaminte Chaayakada in Calicut, says his life has revolved around the wonderful fare his city offers. He grew up in Calicut with a deep love of food and is now the owner of a chain of restaurants that are synonymous with homestyle Malabari food. Ice orathi, for him, is a nostalgic dish that he calls “the common man’s dessert”. He remembers how ice orathi was even a “betting term” for youngsters like him growing up around the city in the late 80s and early 90s. (For example, kids would wager, “If I beat you by this many points, you buy me two ice orathi, or if I lose, I will buy you a special ice orathi.”) It was a simple pleasure that was also considered marvelous and astonishing because of its unexpected flavour combination.

Monashree equates ice orathi stands to “a local beach Subway, where we can choose the toppings and the flavours we want”. “I like how shopkeepers even add their own touch of flavour to it,” she says. “For instance, one of the shop chechis had Boost-flavoured orathi.

Aneez recalls a time mere decades ago when now common flavours such as vanilla and butterscotch were unheard of in ice orathi. “Every day, after a game of cricket or football, we’d go have ice orathi, specifically the spicy and sweet versions, “ he says. “We had plenty of opportunities to try all its flavours.”

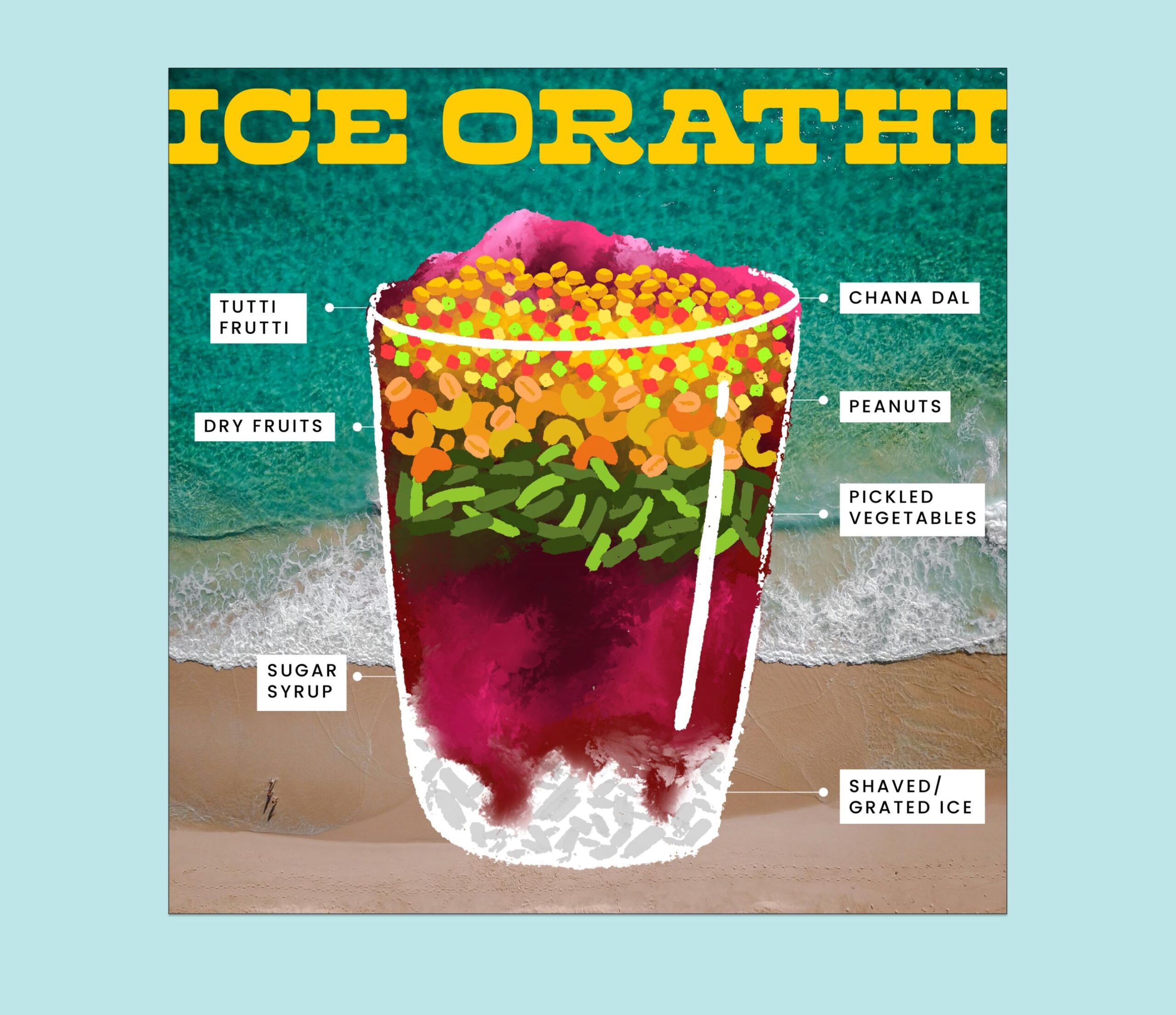

The ice orathi experience begins even before you take your first bite, it starts when you walk up to the pushcart, take in the pickled and/or sliced veggies, fruits, and toppings. These are typically unripe mango, beetroot, and carrot filled in glass jars, and freshly cut pineapple and watermelon. Once you’ve picked your preferred flavour combination of sweet, sour, spicy, salty, you get to watch the vendor shave the block of ice into a cup, add sugar syrup, brine, and vinegar along with layered pieces of pickles (if you’ve picked them), a little bit of khus khus, tutti frutti, and chana dal, all of it presented with a final flourish. For Adam, “this combination of shaved ice with sarsaparilla syrup, paired with different pickles and add-ons, from chilli and lemon – sometimes in custom variants – was our introduction to the world of flavours”.

As the dish hits the tongue, your taste buds might get a little shocked and confused – the combination of flavours and textures might seem unusual, and perhaps therein lies orathi’s joy. Harishma Girish, an entrepreneur from Quilandy who has khus khus in her orathi every time she went to the beach as a child, agrees with this notion. “It’s a fun adventure in your mouth – sweet, briny, crunchy, and spicy,” she says. “One might never know what they will run into [in any bite]. It has its way of surprising us, just like life does. While we no longer go to the beach as often as we should, nor do we enjoy the ice orathi as much as we’d want to, every time I see an ice orathi, it brings back memories, especially of the people I shared it with.”

This sentiment is echoed by social media manager Tanisha Moopen who now lives in Dubai. She is reminded of the best times of her childhood whenever she thinks of this ice orathi. “It is like having sour ice cream, and who doesn’t love that?” she says. “There are different versions of it across the globe, but the one you get on Kozhikode beach hits differently. As a child, I remember going to Kozhikode Beach after the iftar with my family during Ramadan. It was the only time we had ice achaar, it was a special treat. It is a very simple preparation, made of things that you can find at home. But when it’s made on the thallu vandi (push carts) by vendors (and their questionable hygiene standards), it tastes different, especially when shared with loved ones.”

Even for first-timers who have conflicting feelings about the flavours they encounter in an ice orathi, it remains a must-try experience in the food landscape of Calicut. Monasharee Muralidharan, a 25-year-old art manager and architect who currently lives in Calicut, still has mixed feelings towards the dish. It’s not for everyone, and could easily be overwhelming for an unaccustomed palate. Sreelakshmi E, an assistant professor from Calicut has loved it all her life. Others remember the dish fondly, but express concern about whether their bodies can still handle the ingredients.

It is ice orathi’s element of customisation that most fans swear by. Monashree equates ice orathi stands to “a local beach Subway, where we can choose the toppings and the flavours we want”. “I like how shopkeepers even add their own touch of flavour to it,” she says. “For instance, one of the shop chechis had Boost-flavoured orathi. The important thing is, when you order an ice orathi, you watch them make it and engage with the process. It tempts you to experiment even more.”

Even today, on the hot humid shores of Calicut Beach, ice orathi is priced at Rs. 20 per glass. It’s a hyperlocal dish and an experience – one that offered a ‘build your own dish’ format before the dawn of brands like Subway or Baskin Robbins. It continues to provide infinite possibilities, and its sense of whimsy is perhaps why people keep coming back to it.

Today, according to Adam, a lot of new variants are available on the beach, but the original ice orathi will always simply be shaved ice with either pickles or sarsaparilla syrup or a combination of these in varying ratios. While the origin of this simple dish is a mystery, this much is sure – for decades it has provided respite from the heat and humidity on the beach, and it continues to be an important part of the local culture.

Unlike many other shaved ice desserts, there are no elevated variants of ice orathi available in bigger shops. It continues to be a beachside legacy dish that children still bet over, and youngsters dare each other to experiment with. It is enjoyed by families from all walks of life while they’re strolling on Calicut Beach. Most importantly, it leaves an indelible memory, even in those who tried it but didn’t particularly enjoy it. It is the quintessential sensory impression of Calicut.

All images were taken by Gokul Varma.