What does growing up as an Army kid teach you about food, rations, creativity, and resourcefulness? Ishita Thakur’s light-hearted essay is ribboned with stories of grit and moments of great joy.

Both my grandfathers and my father have contributed to how the Indian Army eats.

I was around nine years old when I realised that #NotAllMums bake bread, puff pastries, or giant butterfly-shaped cakes at home for their kids’ birthday parties.

The year was 1997, and my father (who was then a Major in the Indian Army) was transferred to New Delhi. It was the first time we were living in a big city. I was among 30 fifth graders celebrating my classmate’s birthday at McDonald’s, and there was nary a homemade chicken puff in sight. The idea that party food even existed outside one’s home, or an Army mess, was a delicious and disruptive concept to my young mind. It made me realise I was different, and so was my family.

As a third-generation child of the ASC or Army Service Corps, obsession with food, fresh ingredients, and culinary sensitivity runs in my blood. Allow me to elaborate. The ASC is the Indian army’s oldest service (it’s been around for over 250 years!) and is responsible for supplies and logistics, including food, rations, fuel, and other necessities for the troops. Both my grandfathers and my father have contributed to how the Indian Army eats. I recall watching in awe as soldiers meticulously loaded food supplies, fuel (and sometimes even ammo) onto various modes of transport – helicopters, massive trucks, and even tiny mules that set off to far-flung posts across the country. No mountain was too steep, no border too dangerous. The ASC’s mission was to deliver not just sustenance, but also a bite of home.

The ASC isn’t just about logistics. They also train the army’s cooks and servers to make the most out of food supplies, thus ensuring that the corps receives consistent, familiar menus across every base. I dare McDonald’s to make dal tadka taste at 12,000 feet as it does at sea level. Every Millennial fauji kid remembers the menu from each unit gathering, house party, and mess meal. They are all the same. Our bat signal is egg toast, fruit custard with jelly, and (after a few Old Monks), a penchant for trashing “these civilians”.

Cornflakes could make everything from fish fingers to last minute barfi. My mother had developed a range of cooking that could put an AI-powered Instant Pot to shame.

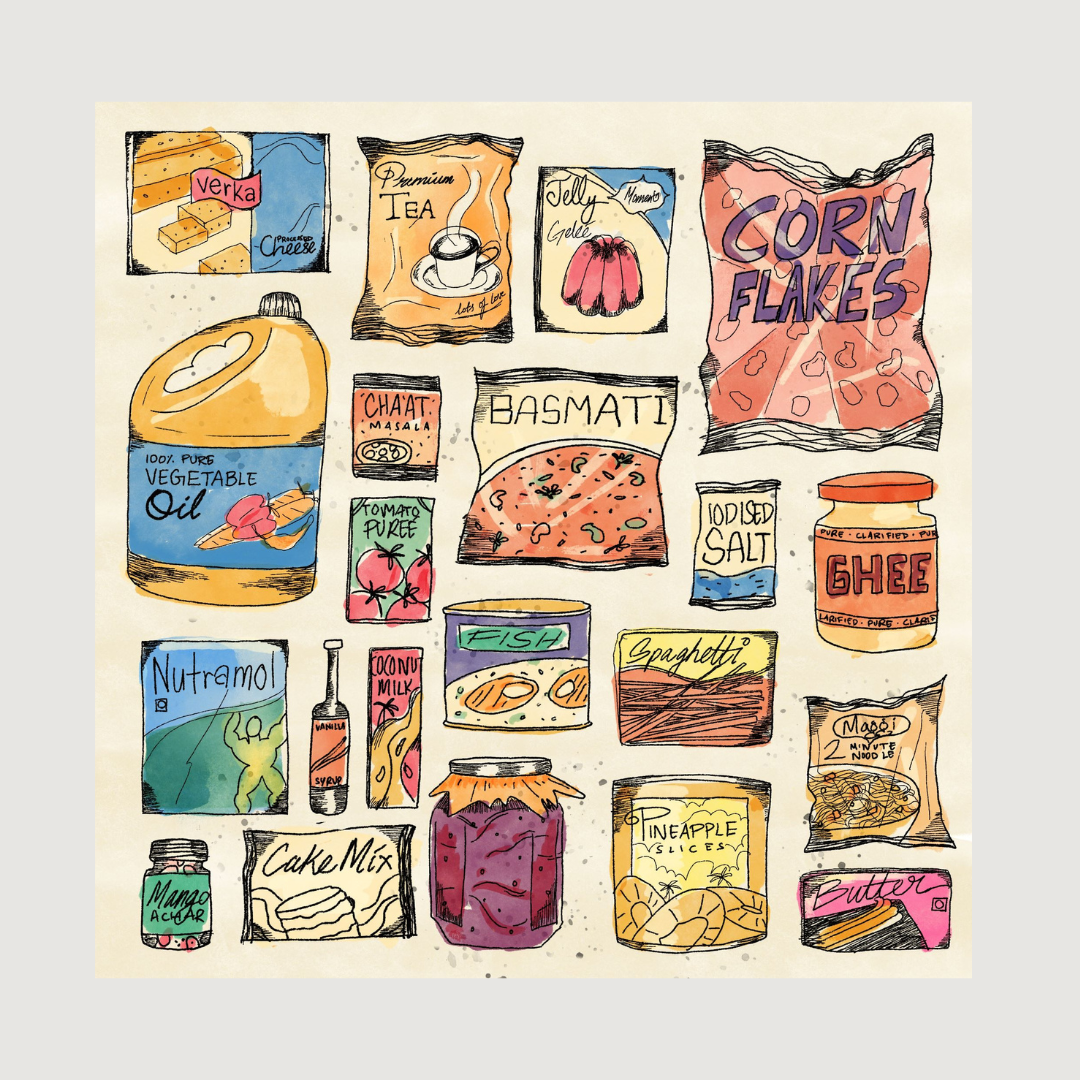

I grew up in the ‘90s, with my family of four, stationed in small towns. We relied on local supplies and monthly entitled rations that showed up in a green crate, much like MasterChef’s mystery box, but with tinda and lauki (which explains why nine-year-old me wanted to live in McDonalds). Don’t get me wrong, we ate well. It wasn’t glamorous, but it provided consistency – a blessing in a life full of moves.

The task of stretching each ingredient and bringing Gary Meighnan’s level of kitchen creativity to the family (and their bougie beagle) fell on my mother. An army child herself, the journey of new wife and mum began with epic fails from burning down the oven, to forgetting the gas while frying masalas while simultaneously helping me with Math homework.

After several rescue meals from the unit mess, she cracked the code of cooking with limited resources: create, conserve, and innovate. She could convert a single bottle of standard issue jam and custard powder into a new dessert. When the jam was mixed with hot water, it made our version of ‘Tang’ on the go. Cornflakes could make everything from fish fingers to last minute barfi. My mother had developed a range of cooking that could put an AI-powered Instant Pot to shame.

Like my mother, other fauji families had their own version of innovating with limited food supplies. Instant noodles made for delicious kheer. Milk powder made gulab jamuns. Malt powder subbed in for cocoa in cakes and cookies. Everyone’s favourite appetiser? Tinned pineapple, cubes of processed cheese, and a tinned cherry on a stick. Dinner parties at home were culinary play-offs with families vying for the title of “Kya khana tha!” up to two weeks after the party.

The shared agenda to eat well with whatever was available created a culinary camaraderie, especially in a community where home parties, ceremonial dinners, high teas, ladies’ clubs, and mess gatherings were on heavy rotation. The army, it turns out, thrives on a healthy dose of both rations and revelry.

Army life taught me that the most delicious meals aren’t always about fancy ingredients or elaborate recipes.

My favourite gatherings were block potlucks, when willing families would pool their meat rations for a blowout barbeque. Each family would also contribute a dish to the potluck, made from the same rations but with a regional spin. As a child these barbecues were a delicious passport to Orissa, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Kerala and other states, courtesy the diversity of army cantonments.

Another important army tradition which tested each family’s ability to innovate in the kitchen, were times when officers would drop in unannounced to one’s home. Imagine having to feed 20 people with zero warning! The lady of the house had to make do with whatever was available at the time to create a wholesome and a memorable meal. My mum could whip up anda bhurji, parathas, mix veggies, and bread pakoras in under an hour, and serve it all langar-style for the waiting crowd. Army wives have been acing pressure tests since before MasterChef was even conceived.

Meals shared and recipes discovered are part of our community’s legacy. These practices went beyond the confines of our own kitchens, and extended across the country, especially in times of need and natural calamities. During the 2014 Kashmir floods, army wives aided in relief efforts and came together to churn out massive batches of mathris and shakarpara – instant energy snacks for those impacted. They also mobilised donation drives of blankets, tinned foods, medicines, and warm clothing, for affected families.

Army life taught me that the most delicious meals aren’t always about fancy ingredients or elaborate recipes. The real magic lies in resourcefulness, creativity, and the joy of breaking bread with people known and unknown. Making the best of whatever one has isn’t just an army-brat trait; it’s a recipe for a fulfilling life, and an attitude I’ve carried through life beyond army cantonments, especially in times of financial hurdles, geographical displacement, illness and homesickness.

Whenever I am faced with a difficult decision, I toss all possible options into my mind’s green ration crate, knowing that even if I pick a lauki, I can turn it into a three-course adventure. Here’s to all the army brats on their own journey, from rations to riches – may you always leave room for dessert, even if it’s made from just jam and custard powder.