On kinetic, roving breakfasts in Arun Kolatkar’s ‘Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda’

The series of poems, Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda by Arun Kolatkar, doesn’t start in the mentioned South Bombay neighbourhood. The first six poems move around the world, and even outside it: when on a Russian spaceship, the poet declares that the cosmonauts “have just finished their breakfast / of pork, cheese, honeycake, prunes, and coffee.” Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda is a series of 31 short poems from Arun Kolatkar’s 2004 volume Kala Ghoda Poems. The poems’ point of view cuts cinematically between breakfast snapshots around Poland, Peru, America, West Africa… and even when they arrive in in Kala Ghoda, Kolatkar zooms in yet again, to “the third [concrete] block from the base of the isosceles counting from the Wayside Inn side.”

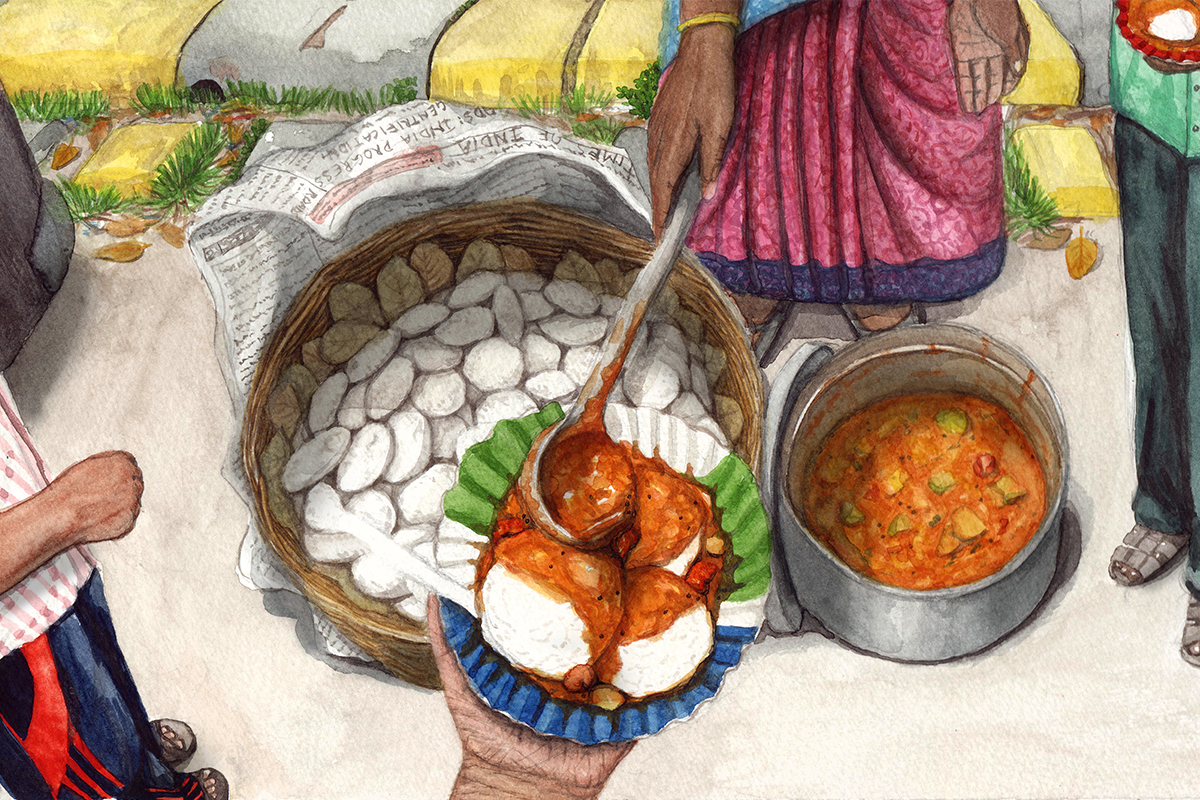

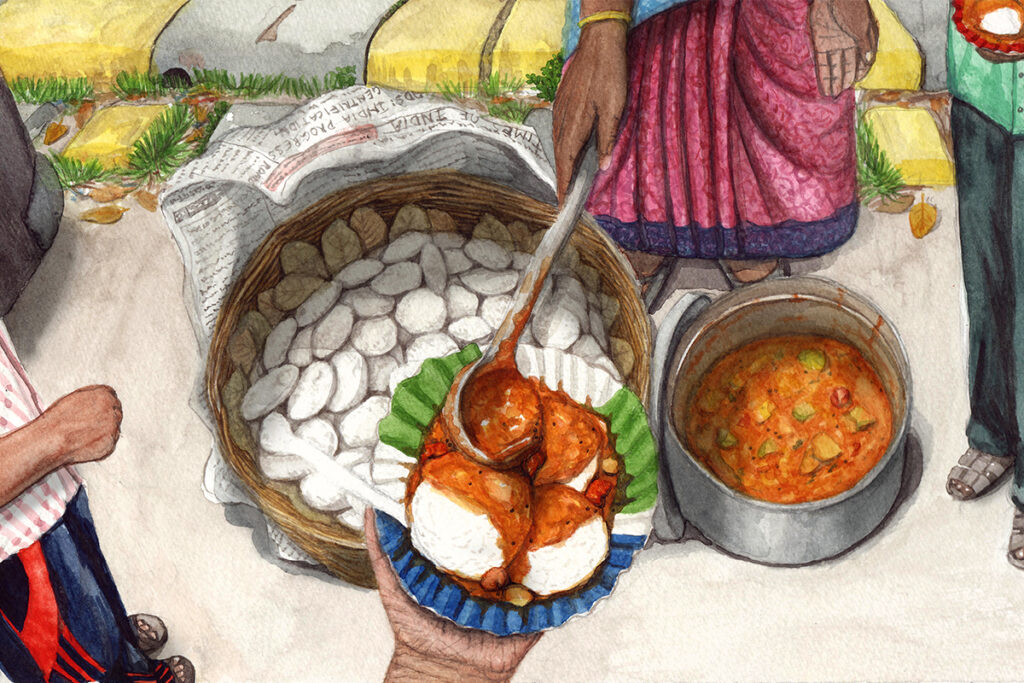

It is here precisely that we meet the main character of the poem series, Annapurna, “Our Lady of Idlis,” who has arrived with a tin of idlis and a bucket of sambar. She comes with “a head of wirewool hair, / peppercorn eyes, / and a smile for everybody.” For sambar, “you’ve brought your mug, right?” the poet teases. “I told you, didn’t I?”. Despite the arrival,

Kolatkar’s poetic eye never lingers. It is always in motion, surveying the scene. Who is here for breakfast, who is late, who is on their way? What’s going on over there?

“They’re serving khima pao at Olympia, / dal gosht at Baghdadi, / puri bhaji at Kailash Parbhat…” Kolatkar writes in the seventh poem of the series. “It’s breakfast time in Kala Ghoda,” he announces. And we are there with him.

As to others who have written about Bombay (Maximum City, as we’ve all heard), to Kolatkar, the city is always in-motion.

But what Kolatkar does differently is to infuse everything, every cell of breakfast with energy and metaphor, turning what might be perceived as mundane into something sublime.

“In Kolatkar’s burgeoning, ever-surprising world, there is no such thing as inanimate,” writes poet Karthika Nair about the collection in an article. “Everything – pinwheels and bicycle tyres, coconut fronds, dead leaves or prawn shells, castoff condoms, idli and sambar, breasts and buttocks – is sentient, is marvelously kinetic.”

Take Kolatkar’s idlis — which are rowdy, horny, personified at every turn. They tumble out of the dabba, as “a landslide of full moons”. From the almond leaf-lined basket, they pair off in bowls, mugs, and kachoris; they “lie gasping, / belly to belly, / or hump each other / like turtles / in the mating season.”

In poem 24, my favourite, Kolatkar writes:

Idlis,

plump and spongy lenses,

magnify our appetites;

And through the telescope

of shared hope,

bring the stars within our reach.

In my Intro to Poetry class, I recite aloud, gesticulating broadly toward the back of the classroom. I repeat the poem twice. Once, mid-recitation, I started to cry. When I start to go off about “shared hope,” students begin to chuckle. “Ma’am? It’s nothing serious? It’s just idli?” they say. “JUST IDLI?!” I holler, a little feral. Not to Kolatkar, who knows that “every hungry and homeless soul” has come “to receive the sacrament of idli, to anoint plates with sambhar”. And not to me.

Most fundamentally, in these poems, Annapurna and her mobile idli stall represent a democratic and utopian vision for the neighborhood. But it’s only really a public space when the public takes over, when food is shared. The idli seller creates “a bubble in time, / shimmering with the joy of living, reflecting all the colors / of hope, / and about forty-five minutes across.” When the idlis are gone, the whole scene dissipates “like a castle in a children’s book.” Back to reality, the traffic island’s “flat, old, boring self.”

And what a reality it is — “Shit city!”, Kolatkar writes. “One big high-rise shit waiting for God to pull the flush.” Kolatkar refuses to avert his gaze from Bombay’s trash, the trash pickers, the stray dogs, the down-and-outers. “The little vamp, the grandma, the blind man, the ogress, the rat-poison man, the pinwheel boy, the hipster queen of the crossroads…” Kolatkar looks squarely at his characters and he writes about them.

I am drawn in by Kolatkar’s poetic lists, the tendency towards expansion and inclusion. But I must confess that I also find all this a little patronizing. I imagine Kolatkar sharing breakfast among his friends, the mustachioed left-literati, looking through the glass of the Wayside Inn at homeless people passing, milling, living outside. This tension between the veneer of social capital and the depth of economic inequality defines not only this poem series but also, I think, Kala Ghoda: which is defined by its artistic and literary heritage, its show of richness offering no benefit to those who inhabit its streets.

Since the publication of Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda, India’s culinary narrative has become increasingly and dangerously homogenised. Even seeing a poem stuffed with kheema and kebabs and gosht and baida and paya and bacon makes me jittery.

When Kolatkar mentions nalli nihari at Noor Mohammadi’s, I actually become (posthumously) nervous for him. But this isn’t Twitter. This is a book of poems. And so, in a long series of poems about breakfast, Kolatkar can include “thirteen high-caste Hindus … / forcing four Dalits to eat / human excreta, / which is to say, shit… for / letting their cattle graze / in the jowar fields / of an upper-caste landlord, say, / if not for / some other / reason.”

There are limits to what a poem can do, but a poem is filled with power. This mix of newspapery euphemism and Bambaiya straight-talk, the irony, the tonal tightrope – it’s poetry that gives Kolatkar’s voice its utopian and political force. Only poetry brings us these indelible, rumbly-tumbly idlis, which can help us see the scenes and crevices of Kala Ghoda’s landscape with new eyes.

I first pulled Kala Ghoda Poems off my then-boyfriend’s bookshelf in San Diego in 2012 when I had never eaten an idli. But these poems made even foreign, far-away me feel welcome. I was so surprised when I visited the spot where Annapurna stands with her basket in real time and realized that it’s literally a parking lot, cars squeezed tight like tinned fish, their mirrors folded back neatly against their bodies. Kolatkar’s Kala Ghoda is an ethos, resisting changes in the neighborhood, and incoming gentrification. “Boy am I glad they’ve left / at least / this one little traffic island alone, / haven’t landscaped it to death, / put a fence around it, / slapped logos all over it,” Kolatkar muses ruefully in his poems, describing and predicting incoming gentrification. And so, while Kala Ghoda can be developed and re-developed, we can build Kolatkar’s world anytime we please. We can build it, these poems insist, with language.

Lily Kelting is an assistant professor of Literary and Cultural Studies at Flame University. Her writing appears in Vittles, Gastro Obscura, The Kitchn, and elsewhere. More @lilykelting.

Illustration by Shawn D Souza