Art imitates life in our kitchens and at our dining tables. Screenplay writer Sumit Roy (Gehraiyaan, Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani) writes about how cinema holds up a mirror to the everyday politics of our food.

I spent my mid-twenties trapezing between several eclectic gigs, pretending it was a career. On one such adventure, I found myself in Old Delhi, assisting Margaret, a winsome, indefatigable New York writer, who was on assignment tracking down Mughlai food recipes for a fancy culinary magazine.

We were a battalion of four marching through the frantic lanes next to the Jama Masjid; our researcher Sunil, a quiet, bespectacled lad with hypnotic patience, and our middle-aged driver Pandey Ji, a jovial repartee-a-minute wise-guy, the other members of our party.

Our mission – locate the elusive ingredient X of Karim’s famous speckled mutton korma – a masala mix, the secret of whose existence had been revealed to us by their khansama. Unfortunately, the treasure was only available in a specific shop, hidden somewhere in the confusing entrails of those gallis.

But for a nation that swears by maa ke haath ka khaana, it’s kind of ironic that the people most likely to be excluded from dining tables across the country are our women.

It was a hot day, we had already spent an hour exhausting ourselves searching for the shop, and our stomachs were growling. I picked a place where we could eat – a promising hole-in-the-wall kebab shop and asked Pandey Ji to grab us a table. To my surprise, the cherubic chap walked away in a sulk, telling me he couldn’t eat with us.

Perturbed, I went up to him to enquire what was wrong. After some gentle nudging, he suddenly pointed towards Sunil and burst out indignantly, “Hum Ganga ghaat se hain, ch*m**r ke saath khaana khayenge to swaad nahi aayega.”

I was taken aback. I’d thought he was constipated, but this was a far more civilisational blockage. Leaving him be, I found the rest of us a table. I watched Sunil’s intense eyes stare at the menu – there was no way of telling if he’d heard what had been said, he gave nothing away. I found myself wondering how many times might he have heard similar words uttered at a dining table before.

The memory of that moment returned as a hot vivid flash when I was watching the short film Geeli Puchi, part of a Netflix anthology called Ajeeb Daastaans, more than a decade later. The film is ostensibly a Dalit woman’s love story, but with what seems like surgical accuracy, depicts the politics of exclusion through food.

Bharati Mandal (played by Konkona Sen-Sharma) works on a factory floor full of men and eats her lunch alone in the canteen. When she falls in love with Priya Sharma, a white-collared Brahmin woman (played by Aditi Rao Hydari), Bharati disguises her caste status, passing herself off as a Brahmin. A fledgling romance springs to life between the two, over shared tiffins and street side dahi vadas. But later when Bharati reveals the truth about her subterfuge to her paramour, suddenly the reality of the class and caste divide between them sinks in.

In a cruel heartbreaking moment, when Priya celebrates her birthday – Bharati is not invited in and is instead given the job of serving cake and cleaning up the dirty tissues.

When she visits Priya’s house later. Everyone gets to drink tea in porcelain cups. Bharati gets a steel cup. Food in cinema, like in life, can become an instrument of denial. Just like it is in almost every Indian household.

One person’s odour is another person’s cultural memory; an umbilical cord to home and a community’s history. This is why its denial hurts us so deeply.

In the last film I wrote, Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahani, a patriarchal matriarch – not as oxymoronic as you think – Dhanlakshmi Randhawa (played by Jaya Bachan) leverages her control over her halwai family’s traditional boondi laddoo recipe as a means of excluding her bahu-in-waiting Rani Chaterjee (played by Alia Bhatt) from the family fold.

But for a nation that swears by maa ke haath ka khaana, it’s kind of ironic that the people most likely to be excluded from dining tables across the country are our women.

This legacy of that generational trauma is on display in the Malayalam film The Great Indian Kitchen, in which a newly married bride (played by Nimisha Sajayan) quickly discovers that her in-laws don’t just want her to cook chutney OR sambhar with their dosas – they want her to make both. Her father-in-law, a traditionalist, insists she doesn’t use a blender (where’s the flavour in that?), he wants his chutney hand-ground, his rice slow-cooked over the fire. And of course, she is expected to clean up after the men, once they’ve eaten.

Watching this film was painful, akin to being battered by a blunt instrument with a metronomic rhythm. It forces you to experience the relentless monotony and degradation that is a daily ritual in so many households. That’s also why the film is effective. It doesn’t offer the audience an easy release, just like the bride at the centre of the story isn’t afforded one.

Axone (pronounced akhuni) gives us a whiff of a wholly different type of denial through the story of a bunch of young North Easterners living in Delhi, who are looking to cook the namesake traditional Naga delicacy. A fermented soy bean gravy with a strikingly strong smoky aroma, it’s the axone’s pungent smell that becomes a challenge in its preparation for our protagonists. Their Punjabi landlord debars them from cooking up their ‘smelly’ food, forcing them to deploy trickery and comic subterfuge to get the job done.

In the film, the axone isn’t just a meal, it represents a yearning for connection for these young immigrants, living away from their homes. The brutishness of a fatwa against odour was immediately recognisable to me as someone who, growing up in Delhi, got asked quite often how we Bengalis could tolerate living with such smelly (fishy) kitchens. Many Muslims looking to rent flats in our great metropolises are routinely declined, with the very same reason cited.

One person’s odour is another person’s cultural memory; an umbilical cord to home and a community’s history. This is why its denial hurts us so deeply.

I was thinking about how to bring different worlds together that day years back in Old Delhi, as Margaret, Sunil, and I wolfed down absolutely sublime seekh parathas, and mutton nihari.

Food is personal. It’s an intimate act.

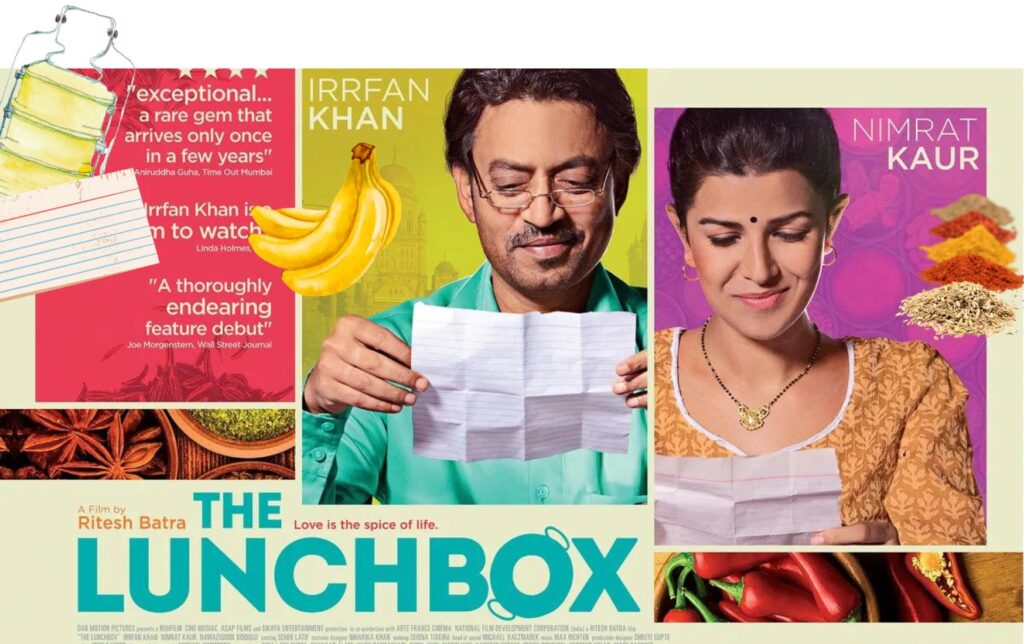

And it’s this intimacy that gives food the power to will into existence relationships that never existed. Like in The Lunchbox where a delightful twist of fate (and mixed-up dabbas) leads to Ila Singh (played by Nimrat Kaur), a lonely housewife developing a bond with Saajan Fernandes (played by Irrfan Khan) over her bhindi ki sabzi.

The two never meet in the film, their love language is letters and her recipes. When Ila gets upset with Saajan, she adds more spice to the sabzi she sends him. He writes to her that he was forced to eat bananas after lunch (also pointing out that a couple of bananas is lunch for many in the city; they’re cheap, they’re filling – they’re good for motions). The food she cooks becomes a chance to be loved for Ila, it awakens the possibility of finding companionship for Saajan.

In the Malayalam film Ustaad Hotel, another kind of companionship is forged over food. Faizi (played by Dulqueer Salman), a deracinated young man who has trained in Europe to become a chef against his father’s wishes, rekindles a relationship with his eccentric grandfather Ustaad Kareem (played by Thilakan) who runs a small hotel in Kozhikode. The time with his grandfather helps Faizi reconnect with his roots and with a sense of community. He ends up pairing his Kerala parathas with Spanish omelettes, bringing his two worlds together, so to speak, on the plate.

I was thinking about how to bring different worlds together that day years back in Old Delhi, as Margaret, Sunil, and I wolfed down absolutely sublime seekh parathas, and mutton nihari. Pandey Ji was shuffling outside the restaurant, eyeing our plates hungrily. I called out to him to ask if he was sure he didn’t want to eat with us.

Nostrils flaring, he glared at me and then a small miracle happened. ‘Thoda khaa hi lete hain,’ he said, melting a little. He waddled over to our table.

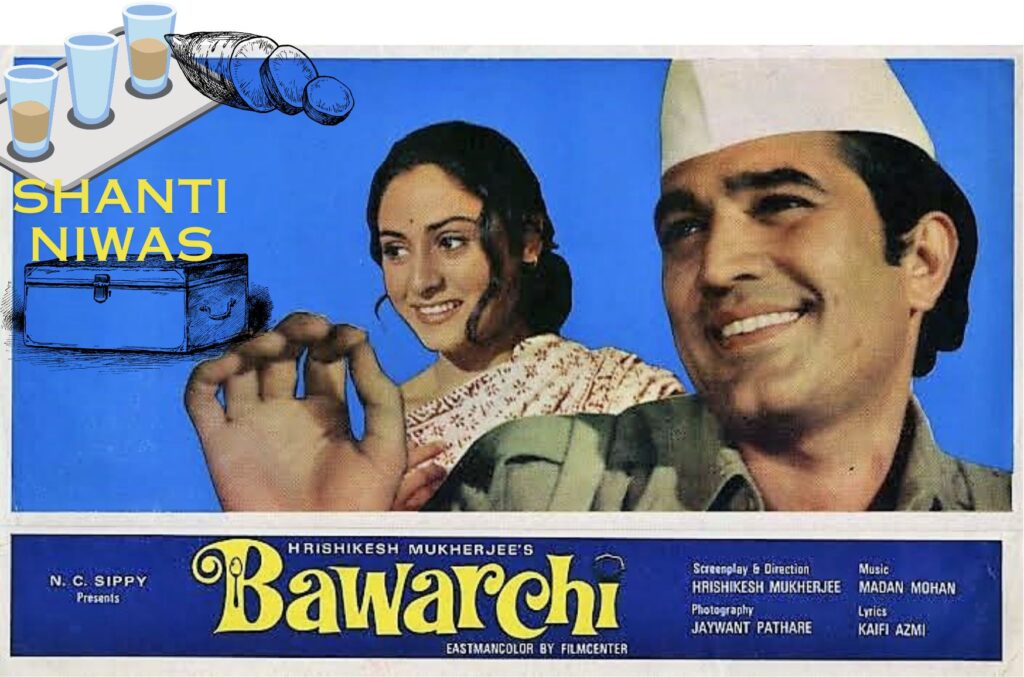

Temporarily, hunger had won over years of hardwired conditioning. As the four of us ate ourselves into a collective food coma, I marvelled at food’s ability to bring such a disparate group together in an act of shared ecstatic communion. Like that old feelgood favourite from long ago, Bawarchi, in which a charismatic cook (played by Rajesh Khanna) brings together a family that can’t stand each other, with his cooking.

And then in a moment that felt almost too good to be true, as Pandey Ji ravenously tore into his food, Sunil stared at him poker-faced and asked, “Swaad to fir bhi aaya naa, Pandey Ji?”

Sunil had overheard him after all. All Pandey Ji could offer was an embarrassed nod.

Perhaps we’d found a secret masala after all that day, one that might even bring the great big dysfunctional family that is our country a little closer together. All we need to do is be a little more thoughtful about who gets to share our table and who doesn’t.