Mahatma Phule Mandai in Pune has a rich and storied history tied to that of India, says floydiancookery. For one, its Victorian Gothic style was inspired by a jail

“It was a theatre of life, a vibrant performance unfolding before my eyes.”

In the hazy corridors of my memory, a carousel projector shines grainy pictures of my first market visit onto the white screen of my hippocampus. Click – a massive stone tower daunting over me – click – an old woman with a crinkly-eyed smile offering me a slice of raw mango – click – a drop of water rolling down the side of a glossy brinjal – click – a dog being shooed away by the carrot seller – click – my mother’s hand guiding me through a thick maze of people.

These images play out to the song of people laughing, women bargaining, birds chirping, and children crying, putting all the recent Wes Anderson-styled Instagram reels to shame.

I revisited Mahatma Phule Mandai, a vegetable market located in central Pune, a month ago to research my piece for enthucutlet. The moment I stepped onto the cobblestone path, an electric current of nostalgia surged through my veins. It was a theater of life, a vibrant performance unfolding before my eyes. And in the midst of this spectacle, I, a wide-eyed spectator, stood captivated.

That was until a familiar voice broke my trance — “Keli ghya keli…”

The roofed flanges also helped in providing shelter to the prisoners against rough weather while segregating them according to the crimes committed.

“Ghya keli ghya!” shouted the fruit seller, the strong afternoon sun feasting on his produce. The year was 1868. It had been forty years since Shaniwar Wada, the stronghold of the Peshwas, had burned down. What was once an open market with a sturdy backdrop of the stone capital, had now been reduced to a disorganised rubble of fruit vendors and vegetable sellers scrambling to make a living. As has been the story of humanity since we were but mere compounds floating aimlessly in the primordial soup – through this chaos was born an opportunity.

Now the British wanted one thing and one thing only: a chokehold on the trade and commerce of their colonies, especially India, considering how much she had to give. Enter Walter Ducat – a freshly minted coin in the purse of the British Royal Engineers. Mr. Ducat hated two things: bad design and the poor hygienic conditions of Poona. While doing his research to improve the sewage systems of the city, he realised the need for better market spaces. Ducat thought purely from a civic perspective, although his higher-ups had other ideas. The newly constructed Crawford Market had triggered the necessity for a similar covered market in Poona. A better market space would allow the British a monopoly on the city’s basic needs. Their Pavlovian salivary response to the sound of this was immediately asking Ducat to propose a plan for the market. Our man Ducat said, “I got 99 problems but a pitch ain’t one,” and within half a year, he had blueprints ready for the market construction.

Victorian Gothic, a revival of the medieval Gothic style, was the architectural rage back then. All the top engineers in Britain were designing ornate structures. Monkey see, monkey do. Ducat decided that he must also be #trending and outlined three main concerns:

- Better hygiene and storage for an increased shelf life of produce

- Shop accessibility from all sides of the market

- Sheltered buildings to protect from the forces of nature.

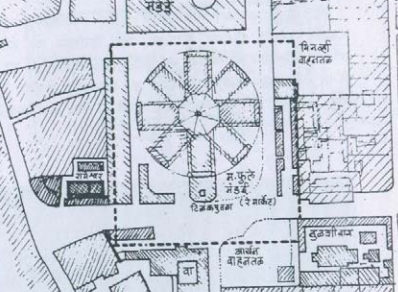

The Gothic aesthetic for the market lent itself perfectly to all three points. The high ceilings and covered slanting roofs – mainstays of Victorian Gothic architecture – would enable ventilation and light even in a closed market structure. The large-scale use of iron meant that the pillars could be much thinner than traditional stone pillars, reducing obstruction in the floorspace and market view from all corners. The closed structure of these buildings would also help the British regulate the market with ease.

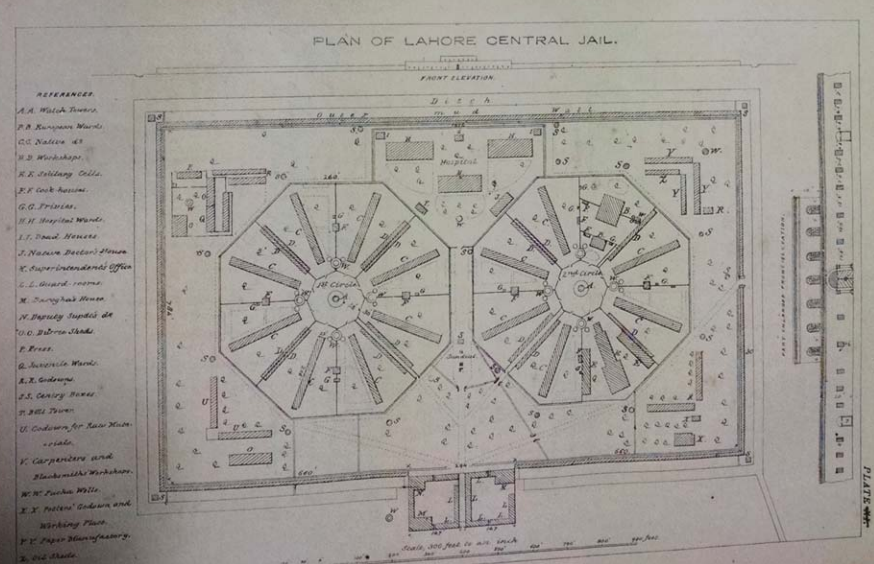

Till the late 1800s, the open market outside Shaniwar Wada was at the heart of the city. It was a massive undertaking to make the new market in Poona equally accessible from all sides. Ducat, just like Anu Malik, believed that copying is wrong but inspiration is fair game. Thus, inspired by the central-tower-with-flanges market designs in England, Ducat proposed the revolutionary design of… a central tower with flanges. A stroke of brilliance in this plan, however, was that the design was also based on Ducat’s observation of prison complexes of the time like the Lahore Central Jail, the prison barracks in North India, and the City Jail in Poona. He noticed that the central tower provided a 360-degree view of all the individual flanges, which was important to maintain order in a prison.

The roofed flanges also helped in providing shelter to the prisoners against rough weather while segregating them according to the crimes committed. In addition, this alignment improved ventilation which aided in reducing illness among the prisoners. These observations led Ducat to propose an octagonal central tower with eight flanges and slanting roofs, where each flange could cater to different types of commodities.

I noticed how the whole complex was much greater than the sum of its parts. While the tower looked beautiful from the outside, every other part of its structure needed maintenance.

While Walter Ducat may seem like the Edmund Hillary of the Poona Civic space, all of this would have been impossible without his Tenzing Norgay – Vasudev Bapuji Kanitkar. An immensely resourceful man, Kanitkar hadn’t formally studied engineering or architecture. In fact, he’d learned everything from his time spent working in Karachi, Baroda, and Poona, which makes him the 19th-century equivalent of the dude who dropped out of college and went on to be the best coder in Silicon Valley. Unfortunately, very little is documented about this local lad, although his contribution to the public structures of Poona is undeniable.

The citizens of Poona opposed Ducat and Kanitkar due to the heavy civic costs of constructing the market. Many thought of this as an unnecessary vanity project at the time. Also since it was controlled by the Brits, there was a scare that they could start charging rent for the stalls in the market. Mahatma Phule and Balgangadhar Tilak were among the many who were unhappy.

The British went ahead with the construction anyway, starting in 1882. They preferred local basalt rock from a stone quarry in nearby Chinchwad, as it was of high quality, durable, and most importantly – cheaper to procure. The iron needed for the skeleton of the building was imported in large quantities via Messrs. Sorabjee Shapurjee. Glass and Minton tiles were brought in from Bombay. The roof tiles were imported all the way from France. The Gothic market complex, replete with stone carvings, gargoyles, tinted glass windows, and ornamental iron pillars, was finally completed in 1886. The market was opened by the then-governor of Bombay, Lord Reay, and thus it was named Lord Reay’s Market after him. But as irony would have it, in 1938 it was renamed after the person who had staunchly opposed its construction:Mahatma Phule Mandai.

It’s funny how much of a tourist I felt in my own city walking into this mandai looking for traces of the years gone by. I noticed how the whole complex was much greater than the sum of its parts. While the tower looked beautiful from the outside, every other part of its structure needed maintenance. That’s when I realised, that what made this last vestige of our colonial past so special, was the people who’d made it their base for the last century and a half. The same people who, unlike me, didn’t have the luxury of romanticising vague things like stone walls and limestone cornices, and trampled vegetables and monochrome pictures of the working class. The same people who continue to give back to the market as much as the market has given to them.

The same people to whom life threw the biggest lemons at, and they still carried on offering lemonade (and keli) with a smile.

Acknowledgement: This piece would have been impossible to write without standing on the shoulders of giants like Vaidehi Lavand (report on the works of Walter Ducat and Vasudev Kanitkar), Avinash Sowani (Haravlele Pune), Jaymala Diddee and Samita Gupta (Pune: Queen of the Deccan), Sahapedia, Maharashtra State Archives, Elphinstone College Mumbai, Deccan college archives and Times archives, among other sources.

Design of the Lahore Central Jail – Ref: Professional papers, Roorkee (Credit: Vaidehi Lavand Mandai report)

Mandai Top View: Top view of Mahatma Phule Mandai – Ref: Sowani, Haravlele Pune 1995 map