While the rest of India was munching through the 1990s’ economic boom on snacks and biscuits, Talilula remembers the decade fondly through her mother’s comforting recipe of chichang mayong, a dish made with chutney and leftover rice.

In 1962, villages of Ao-inhabited areas of Mokokchung district in Nagaland witnessed the flowering of Bambusa pallida, locally known as ashi or ashi süng. A species of bamboo particular to the region, the eruption of ashi is believed to occur approximately every 45 to 50 years. A farmer’s nightmare, these blossoms bore fruit-like kernels that attracted, and germinated the population of rodents, bugs, insects, birds, and animals, that descended and demolished their crops. Villagers were faced with a shortage of food and crops, especially their beloved staple grain – rice.

In 1962, villages of Ao-inhabited areas of Mokokchung district in Nagaland witnessed the flowering of Bambusa pallida, locally known as ashi or ashi süng. A species of bamboo particular to the region, the eruption of ashi is believed to occur approximately every 45 to 50 years. A farmer’s nightmare, these blossoms bore fruit-like kernels that attracted, and germinated the population of rodents, bugs, insects, birds, and animals, that descended and demolished their crops. Villagers were faced with a shortage of food and crops, especially their beloved staple grain – rice.

Known as ‘gregarious bamboo flowering,’ this is a recurring phenomenon in the Northeast state of Nagaland and its neighbouring regions. Just a few years before 1962, around 1958-59, the Mautam famine in Mizoram was caused by the flowering of another bamboo species, Melocanna baccifera, known as mautak in Mizo. Although reportedly not as deadly as mautak, the blooming of ashi still caused plenty of havoc.

While the hills were draped with a stunning vista of blossoms that resembled golden feathery dusters from afar, it had lethal consequences. Famine always followed in its aftermath.

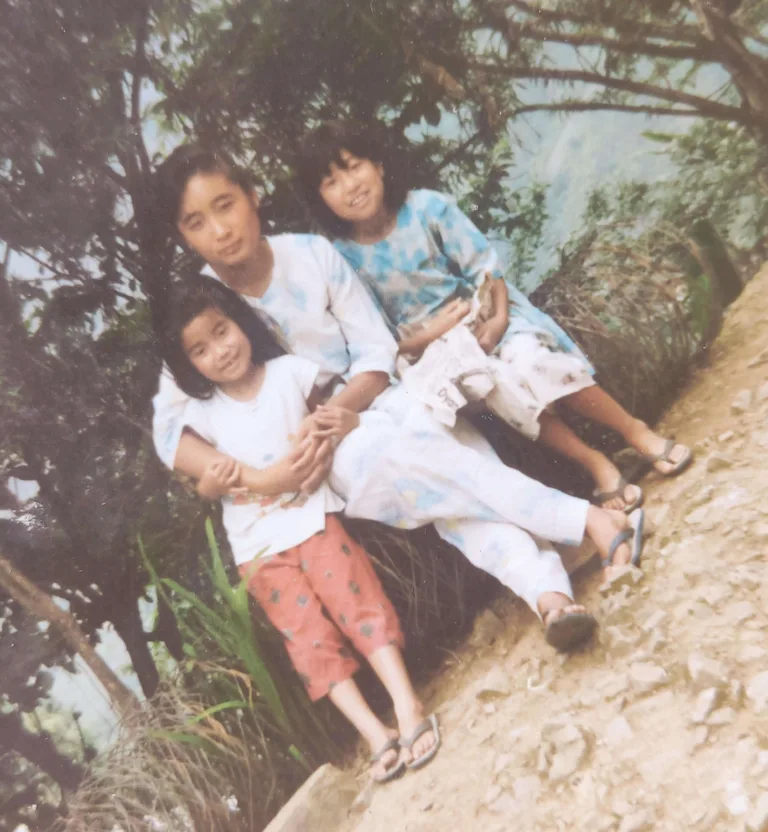

My mother was about ten years old when the ashi flowered in the forests of her village. She remembers this vividly because she had the novel experience of tasting the nutty flavour of the ashi kernels, which were roasted and peeled before being chewed and eaten. The drought that followed was not as bad for her family, because by some sheer providence, my grandmother had saved enough rice grains in the granary from the previous harvest. These were shared with her neighbour who had to sustain a family of ten.

Such experiences instilled in my mother the preciousness, the beauty of rice, so it comes as no surprise then that her most loved recipe is a rice chutney – which she calls “chichang mayong”.

Growing up in the 90s, I noticed that my mother would always make this whenever she or any of us was down with a cold or fever. Or she would also prepare it on ordinary days, where she would announce – “today, I am craving for some chichang mayong”, and begin to prepare this humble legacy that held her childhood memories within it.

The preparation always came with a side of storytelling. My mother told us about how the chutney was created during times of scarcity. While crushing dry fish, chilies, garlic, and tomatoes with a pestle, she narrated tales of hardships that she and the villagers had encountered and overcome. The mayong brought back fond memories of her own mother, working in the paddy fields and foraging for fodder for pigs in the forest. The mayong is not a family recipe with secret ingredients and complex steps, one that is zealously guarded by those who inherit it. It is as simple and unpretentious as it gets. The main ingredient is, of course, rice. In Ao Naga, chichang means rice or rice grain, and mayong is a chutney or condiment served alongside other dishes in a meal. A traditional Naga meal usually consists of rice, some steamed vegetables, a meat dish with a bamboo shoot or a tomato-based broth, and a mayong. A mayong is typically made with tomatoes, garlic, chilies, and dried fish, all of which are roasted and ground into a paste-like consistency (one that is not too fine). The mayong is the binder of a meal, it holds the meal together with sparky, spicy, and savoury flavours.

In Ao Naga, chichang means rice or rice grain, and mayong is a chutney or condiment served alongside other dishes in a meal. A traditional Naga meal usually consists of rice, some steamed vegetables, a meat dish with a bamboo shoot or a tomato-based broth, and a mayong. A mayong is typically made with tomatoes, garlic, chilies, and dried fish, all of which are roasted and ground into a paste-like consistency (one that is not too fine). The mayong is the binder of a meal, it holds the meal together with sparky, spicy, and savoury flavours.

The rice-based chichang mayong takes two of the most important elements of a Naga meal – good-old hearty rice and a mayong – and makes it into a mash-up that is simple, filling, and full of flavour. All you need to create the chichong mayong is leftover rice, some cloves of garlic, a handful of chillies, a tomato, and a few pieces of salted dried fish.

This dish reiterates the centrality of rice, especially for my mother and others of her generation, for whom rice is associated with a multitude of meanings. Rice is filling and comforting, and it can be innovated in so many different ways, especially in times of scarcity. You could steam it alone, or with some yam and tubers, and then have it with some salt; or make it into a broth called thütsü. Or you could spruce it up with edible wild ferns and leaves – like taro – which were typically foraged from the jungles around Mokokchung, where they grew up.

The importance of rice for Nagas is often understated, especially in the context of how Naga cuisines are perceived in contemporary times. In mainstream media, Naga cuisine is marketed and recognized both in Indian and international contexts, more for its non-vegetarian, meat-based fare – like pork with bamboo shoot, pork with axone. With the upsurge in commercial rearing of livestock within and outside the state, the consumption of pork and other meat products have also exponentially increased among Naga people today.

The importance of rice for Nagas is often understated, especially in the context of how Naga cuisines are perceived in contemporary times. In mainstream media, Naga cuisine is marketed and recognized both in Indian and international contexts, more for its non-vegetarian, meat-based fare – like pork with bamboo shoot, pork with axone. With the upsurge in commercial rearing of livestock within and outside the state, the consumption of pork and other meat products have also exponentially increased among Naga people today.

This was not the experience for my mother and those of her generation. Meat was not as readily available as it is now, but instead it was relished during festivals and other significant occasions. Rice, however was at the top of the Naga food pyramid in various iterations: served during breakfast, lunch, and dinner; made into cakes; fermented and drunk as alcohol in liquid and paste form; offered to deities for propitiation; and was the theme of local metaphors and proverbs as well. (My father often used this Ao proverb, ‘anu tayie tzük potak ama’, which means, ‘like drying rice grains at sunset, to exhort about making good use of our time’, by which he meant our study hours.)

For me, decades of being nourished with chichang mayong with the accompanying stories means that I am now conditioned to crave it when I am unwell. It’s in my long list of nostalgic and comfort foods, along with leftover fried rice, French fries, sticky rice cakes with tea, bamboo shoot curry, and crispy fried smoked pork innards. When I moved to Delhi for further studies, I made this mayong on the occasions I missed home, my mother, or when I was just flat broke. In the process, I discovered that the mayong doesn’t taste as good when you use basmati rice (glutinous and aromatic variants work best), and dhania also makes a good garnish.

When I cooked the mayong for my friends, they were intrigued. They had never heard about it, nor was it prepared in their homes – so I assumed that it was probably invented by my mother’s family and villagers when food was not plentily available in their lives. As a dish created from leftovers with no meat, it’s probably not going to be very popular – but for me this dish is an acknowledgment of the history of famine that mother’s generation faced in Nagaland, and their resilience in the face of these hardships. This humble mayong is my mother’s legacy, a recipe that is rich in stories, and is comforting for the soul. It also imparts an important traditional philosophy: if you have a little rice left, then there is some hope.

Recipe

Recipe

Ingredients (all to taste):

Tomatoes

Chillies

Dried fish

Garlic cloves

Salt

Leftover rice

Optional ingredients:

Szechuan pepper, roasted and ground

Coriander leaves

Mint leaves

Method:

Roast the tomato, chillies and dry fish on fire, or over the gas flame.

Peel some garlic cloves, sprinkle some salt and mash them along with the roasted ingredients until it turns into a paste-like texture. It doesn’t need to be super fine in consistency.

Add the leftover rice and mix well with the chutney. The chichang mayong is ready.

If you don’t have garlic, you can use roasted ground Szechuan pepper in its place. Feel free to add coriander or mint leaves as a garnish.

Images: Imti Longchar