How far from the sea, and how hungry do you need to be, to get a meal of sardines and seer? As a doctorate student in Jodhpur, Lavanya Arora found some answers.

It’s never goopy, and always prepared with nutritional value and taste in mind. After all, it has to nurture the growing minds of students who are definitely not going to spend most of their time playing games on their phones. And it never ever uses rotten vegetables and expired masalas. Right?

When I moved to Jodhpur in 2019 to pursue a PhD in Escapism from Responsibilities of Adult Life, I had already lived my fair share of hostel life. So, I knew a thing or two about looking out for cockroach remains in vegetable preparations; or about having a precious, precious stone almost crush my jaw in the yellow water messes ubiquitously referred to as daal. I was prepared. Or so I thought.

The seating arrangement was right out of a thattukada or a shaap. A doorless kitchen right next to it raised diners’ anticipation with its scents of an array of masalas being sauteed, meats being fried or roasted, the clink-clang of utensils and orders flying inside the kitchen.

This institute, and don’t ask me to name names, took it to the next level. It really did have everything mentioned in the above paragraphs. As a top-up, it also had rotis that hardened in the two minutes it took for us to fetch them and sit down to eat. And I mean rock hard. We banged the shiny steel table with them but had to stop, afraid that the table would get dents and we’d have to pay a fine. We even thought of playing discus throw with them several times. Alas, the burdens of academia never let the idea fly.

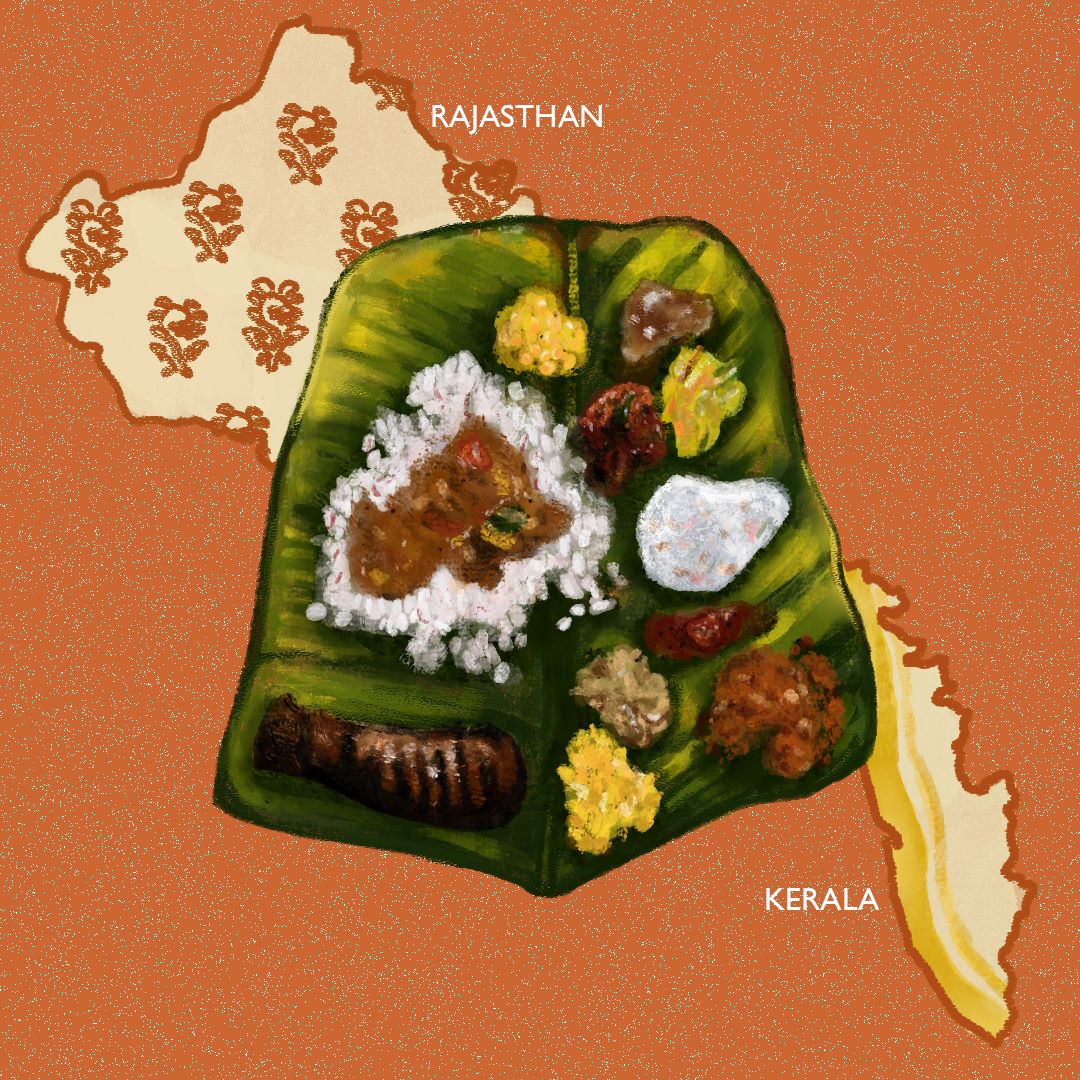

To give the geographically challenged a clue: Jodhpur is also known as the Gateway to Thar. It sits right at the edge of the desert, with the closest point of contact with the sea almost 550 kms away, in Gujarat. It’s also one of the places in India where vegetarians outnumber meat eaters. It’s famous for its khasta kachoris and kulhad-doodh, and of course, laal maas. What I hadn’t the slightest clue about, even a couple of months after the move was that – in this city renowned for its laal maas – I’d fall in love with fried fish.

In any city with a growing transitory population, whisper networks of different communities tend to form. The reasons for these vary – they could range from sharing resources, helping navigate the language barrier, and sharing regional memes, to simply having someone to speak with in a language that feels like home.

Jodhpur, other than being a tourist hotspot and an air force base, has also become an educational and vocational hub in the last few years. It welcomes a steady influx of people from all across the country. With people and communities, food usually tags along. As Malayalis are often known to declare, you can find one of them in every corner of the world. Even next to Messi in Paris. Or more recently, scaling mountains in Antarctica. It was a no-brainer that Jodhpur had its fair share of Malayalis, and so did our friends’ group.

Through one such whispering vine, a friend got to know of a restaurant that served Kerala meals (oonu) and fresh fish in a corner of Jodhpur. We had to head out and give it a chance. After all, we had already tried almost every other café, chaatwala, and restaurant in the city. Even the one that served Korean cuisine. The food at a Kerala restaurant couldn’t be worse than what we were eating daily in the mess, right? Despite the reservations a couple of our friends had about trying fish in the desert, we decided to head there for lunch the coming weekend.

Now, if you know me (chances of which are negligible at best) I love to feed the people I love, and I love to feed them copious amounts of food. Is that an Indian thing or a Punjabi thing? I can’t pinpoint it yet. This also means I want to see them satiated, even if the food isn’t cooked by me. Let me show you where I am going with this.

We finally reached the restaurant. We ascended the one-person-a-time staircase nestled between a grocery shop and an ATM, to face a 12-inch flatscreen blaring old Malayalam songs. It was glued to the wall facing the dining hall. The seating arrangement was right out of a thattukada or a shaap. A doorless kitchen right next to it raised diners’ anticipation with its scents of an array of masalas being sauteed, meats being fried or roasted, the clink-clang of utensils and orders flying inside the kitchen. We could also spot a steel vat filled to the brim with glaring red paste, and next to it, a staff member making diagonal cuts on a variety of fish before spreading the paste all over them, inside and outside the incisions. The joy on my friends’ faces was incomparable. I, on the other hand, was bubbling with compersion. This was about to be my first foray into serious fish eating.

My friends were also delighted to have someone (other than each other) to speak with in Malayalam. With the cheta-mone* (elder brother-younger brother) bond of trust and acceptance formed, the owner of the restaurant (who was also moonlighting as the waiter) suggested we skip the prawns. Rather, he insisted we have the fresh catch of the day. All of these were, to our surprise, fishes found in the ocean: mackerel, sardines, seer, and gar. (He said he got them fresh through a supplier in the Ghanta Ghar market in town. The supplier in turn got it via a daily train route from Gujarat.)

Ignorance might not be bliss but at least it gears you up for adventure. So, along with our oonu, we ordered the fish. With the first bite, we knew we’d return here more often than we’d planned to. We did that, and more. We introduced this place to our juniors, to acquaintances we made while walking around the snake-like streets of the old city, and to Fulbright scholars afraid to try Indian food but still brimming with curiosity about it. Thank you, Anthony Bourdain.

Food is the closest we’ve come to one-way teleportation. You eat a morsel and are instantly transported into a realm of comfort. Scents from the kitchen remind you of helping your mum crush masalas during childhood. Or that one special meal that dad cooked every few months which got more appreciation than mum’s daily toil.

For my friends far from home, getting to experience their much-loved fish fry in the most improbable of places came along with the comfort of language too. So, from them, I picked up a new vocabulary: Aila, mathi, chura, kaari, kanava, kilimeen, koori, karimeen. Each holds a new possibility of flavour.

Also, these aren’t just varieties of fish but also the lyrics of a Malayalam song called Fish Rock by Thaikkudam Bridge. A song I now always play while frying fish at home.

You should try it too.

Kerala Hotel and Family Restaurant, Jodhpur: https://kffcjodhpur.com/

*Literal translation of mone is son. But colloquially, it’s used as younger brother, or even in friends like ‘oh bete’ or ‘arrey bhai’ is used in Hindi. A recent use that made the word famous was in the movie Aavesham. – According to P, one of my Malayali friends.