Stories of a ghee festival, and about a great love for ghee from the mountains of Uttarakhand.

“Ghyu na khala.. banla ghongha /ganel!”

If you don’t eat ghee you will be reborn as a snail, warned a folk saying I chanced upon a few years ago. I am a huge fan of ghee (it’s one of the reasons I will possibly never become vegan), so this aphorism greatly intrigued me.

I indulge in ghee-bhaat once in a while – it is a combination I associate with both my mother and mother-in-law, as well as all the grandmothers in our family. Ever since I became a mother, I also associate it with my children.

There is something intrinsically satisfying and soul-stirring in the aroma of homemade ghee melting into hot rice. Add a sprinkle of salt and the affection of the hands that mix it all into a glistening morsel to feed you, and it becomes a moment of bliss!

Ghee is intrinsic to food across Uttarakhand – whether in the tadka of the varied dals we eat, smeared on millet and atta rotis, bhari rotis or parathas, or drizzled over steaming hot rice, or served by the bowlful in the higher mountains, to dip local bread into.

I learned from my family that the ghee-snail saying is directly associated with Ghee Sankranti, a beloved festival celebrated in Uttarakhand. This region’s ancient belief systems are rooted in Ayurveda. They state that consuming ghee is extremely important, and never more than on Ghee Sankranti. Folks who fail to comply with this diktat will have to deal with dire retribution – they will be born with the attributes of a snail in their next life.

Makhan (white homemade butter) and ghee (clarified butter) have a long, illustrious history in Indian culinary culture. It goes as far back as when cattle were first domesticated, around 1500-500 BCE. Milk was prolific in Vedic-era kitchens, and so yoghurt, butter, buttermilk, and ghee evolved as ways to lengthen the shelf life of milk in a climate where spoilage was inevitable.

There are no written records from these times, but mythology and Vedic hymns offer literary evidence. The Krishna Leela (the story of Krishna), is full of stories of the mischievous deity’s love for butter. Iconography often depicts his mother Devaki churning butter, followed by baby Krishna eating it, or young Krishna stealing it. The Rigveda, of 1000 BCE, also mentions dadhi (curd) and ghrit (ghee).

Most Indian homes traditionally made ghee every few weeks from the milk cream accumulated in that time. Many continue to do so even today. This has also been a long-standing tradition in my Gujarati home, and I remember being thrilled when I discovered that my mother-in-law’s kitchen upheld this ghee-making tradition. There was always freshly churned white butter in the fridge, and the pantry had ghee by the kilo.

A huge jar of ‘Dadi ka ghee’ was mandatorily carried from Dehradun to Mumbai for my kids. One of my fondest memories is of a kadhai of ghee gently bubbling away in Ma’s kitchen, her asking me to get lime leaves from the garden to add to it. The citrus notes these leaves infused into the ghee form the signature scent of the ghee she makes. It’s something I will never forget. My kids are both grown up now, but they continue to love drizzling “Dadi ke haath ka ghee” over their hot rice.

This love for ghee is not just a thing with our family. Ghee is intrinsic to food across Uttarakhand – whether in the tadka of the varied dals we eat, smeared on millet and atta rotis, bhari rotis or parathas, or drizzled over steaming hot rice, or served by the bowlful in the higher mountains, to dip local bread into.

While most of these folk festivals are centred around the worship of local deities – such as those associated with a particular village, community, or family – they play a significant role in environmental well-being.

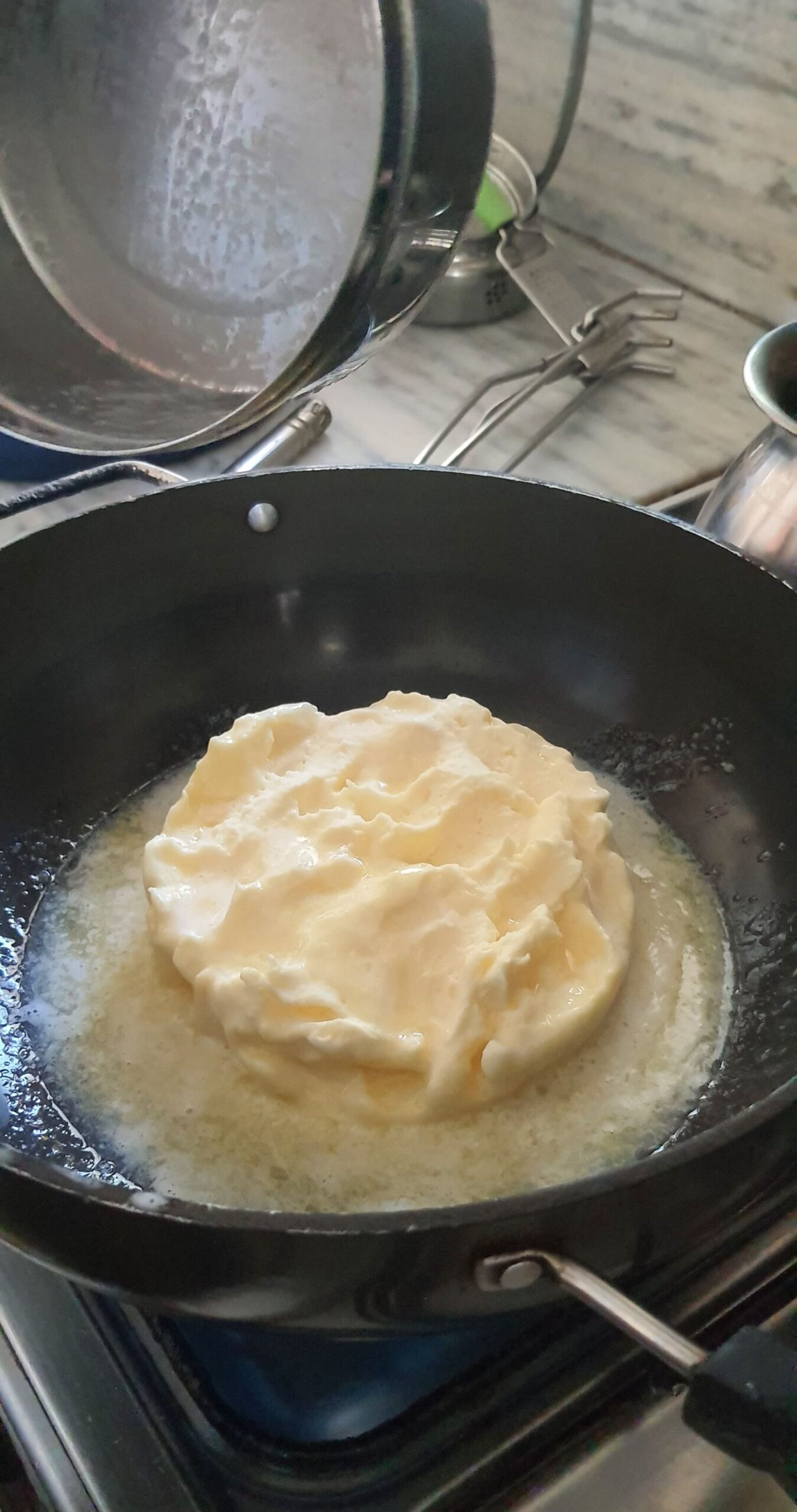

I believe that the best ghee is homemade, and I love the whole process of making it. It begins with collecting cream from milk every day, then churning it until the whey separates, and the fat coagulates into white butter. The fat is then cooked until the milk solids separate from the butterfat, settling at the bottom of the pan, and the ghee – beautiful, golden, and clarified – rises to the top. The labour of this process is rarely acknowledged. Much as the farmer nurtures the harvest, from seed to plant, mothers and grandmothers in the household make ghee. Ghee Sankranti serves to precisely highlight this aspect.

To find out more about Ghee Sankranti, I spoke with my friend Navendu Raturi, the co-founder of Uttarakhand-based brand Namakwali, who is also a passionate proponent of Uttarakhand’s culture. I learned that ‘Ghee Tyar’ or ‘Ghee Sankranti’ is a popular monsoon festival in the state, celebrated in Uttarakhand for centuries. The last day of the month of Saavan or Shravan (in the Hindu calendar), marks a day of giving thanks to nature. The land is flourishing and green for the livestock to feed on, there is an abundance of dairy products and ghee and it is a ritual to eat this ghee and apply it on our foreheads.

Uttarakhand is home to many communities so it has an elaborate calendar of religio-cultural practices dictated by the seasonal agrarian calendar. These manifest in a fascinating array of folk festivals, which follow the lunisolar Vikram/Bikram Sambat or Vikrami calendar. This calendar is only one of several regional Hindu calendars that are in use in South Asia, across the Indian subcontinent, and in Nepal. The Vikrami calendar takes into account both lunar and solar calendars, as well as Vedic astrology and the sidereal zodiac. It is made up of 12 synodic lunar months and 365 solar days, and it begins with the new moon of the month of Chaitra in March. Each month is divided into two halves. The first is the brighter half, called the ‘shukla’ or ‘sud’ paksha when the moon waxes, followed by the ‘Krishna’ or ‘vad’ paksha when the moon wanes.

The term ‘Sankranti’ itself is astronomical rather than religious, and sankrantis are the days in the sun’s sankramaha or celestial journey, when it transmigrates from one rashi (zodiac/constellation) to the next, once each month. There are 12 rashis, and therefore 12 sankrantis, and their dates remain constant over the long term, occurring in the middle of the month on the Gregorian calendar. Makar Sankranti is perhaps the best-known sankranti across India today, however, traditionally each sankranti had significance. Over time some have faded from popular memory, thanks to changing definitions and the precession of the Earth (A phenomenon created by the Earth’s axis of rotation which is slightly tilted at an angle of 23.5 degrees affecting temperatures across the globe, impacting seasons and causing changes in dates.

Even so, some sankrantis are still observed in various parts of the country, especially in Uttarakhand, and across many Himalayan regions in the Himalayas. Mesha Sankranti is celebrated mid-April as Bikhoti in Uttrakhand. Harela, meaning “day of green”, is variously called Harela Sangrand, Mol-Sankranti, or Rai-Sagrān and is observed in mid-July in the month of Assad, on the first day of Shravan-maas. In Uttarakhand, Singh Sankranti is celebrated as Ghee Sankranti on the last day of Saavan, to welcome the Bhado month in mid-August. Makar Sankranti is observed in mid-January. Kumbha Sankranti is celebrated in Haridwar with the iconic Kumbh Mela celebrations. Meena Sankranti is celebrated as Phool Dei or Phool Sankranti on the first day of Chaitra in mid-March, to mark the onset of spring, and it is, in my opinion, the most charming of these festivals. On this day, women wake early in the morning and clean their doorsteps, while little children, especially girls whose visits are considered auspicious, gather and go foraging for spring flowers in the neighbouring forests. They then go from home to home, leaving flowers on doorsteps. For their labours, they are gifted jaggery and money by homeowners. An array of dishes are prepared for this celebration, but the most essential of these is a halwa of rice and ghee called shai, sai, or kasar.

While most of these folk festivals are centred around the worship of local deities – such as those associated with a particular village, community, or family – they play a significant role in environmental well-being. “Ghee Sankranti is also connected to the agricultural calendar,” elaborates Raturi. “This is the time when koda or mandua (ragi), and jhangora (barnyard millet), are flourishing in the fields. This is when the agricultural community expresses its gratitude to mother Earth.”

Something that becomes highlighted by the celebration of Sankranti is the tradition of “Olgia” amongst a few agrarian communities in parts of Uttarakhand. Over time rituals and customs have evolved, of course, but traditionally for Olgia, sons-in-law and nephews gifted presents to their fathers-in-law and maternal uncles. An offering of ghee was still a large part of the rituals. It continues to be so – however, the gifts given to elders, farmers, labourers, and artisans also included tools and equipment, such as axes and metal callipers, musical instruments, money, and the bounty of the season in the form of fruit, vegetables, and firewood. It is believed that walnuts, which come into season soon after and are a big part of the region’s winter traditions and diet, are only eaten after ghee-tyar.

Ghee Sankranti is celebrated to welcome the bhado ritu, or monsoon season when the surroundings are rainy and sodden. Per ayurveda, this is a time when the earth’s ‘fire energies’ are said to rise to the fore, while human agni or digestive fire is heavily dampened.

The foods typically eaten at these festivals are based on seasonality, but also have a more important role to play. Ayurveda places great emphasis on a healthy digestive system for wellness. It put down extensive dietary guidelines on the consumption of traditional foods, many of which have now crossed into mainstream culinary practices. The ayurvedic calendar divides the year into six ritus, or seasons, and recommends a ritucharya, or seasonal discipline for each. This practice focuses on living in tune with nature and consuming a seasonal diet.

Juxtapose the sankranti calendar against this, and we see that each of the sankrantis, especially the prominent ones, are strategically positioned at the beginning of a new season, and the foods eaten on the day of the sankranti are seasonal. Sankrantis and many Indian festivals were tangible signals that the season was changing and that we accordingly needed to adapt our diets to the weather. Community festivities typically included prasad and specific seasonal foods that were said to inoculate one for the season to come.

When Ghee Sankranti arrives, the forests and fields of Uttarakhand are flourishing. “All the foods that season in the forests and fields in the monsoon are eaten on this day,” says Raturi. “This produce, such as moungri (corn), arbi, red rice, urad dal, and seasonal vegetables are all prepared with ghee.”

The dishes vary by location and household. In Raturi’s home, typically corn, patyud (colocasia), red rice kheer with ghee, urad dal ki pakodi, and swaaley (local puri-like bread stuffed with urad dal) are prepared. In my family’s home, we make urad-stuffed bhari rotis (similar to parathas but distinct, in that they are not cooked with oil), colocasia kafuli (a saag-like gravy of colocasia leaves), and rice. There is also a lovely ghee-drenched halwa, and other dishes such as dry-fried aloo or arbi ke gutke, mass (urad dal) ke dade, and mass dal ki poori. For this meal, ghee, urad, and colocasia are a must in some iteration or another.

Ghee Sankranti is celebrated to welcome the bhado ritu, or monsoon season when the surroundings are rainy and sodden. Per ayurveda, this is a time when the earth’s ‘fire energies’ are said to rise to the fore, while human agni or digestive fire is heavily dampened. And so, ayurveda prescribes daily rituals and a diet that will balance things out. Nourishing, savoury, sour, and oily foods are recommended in this season – and the Ghee Sankranti menu reflects this.

To delve deeper, I met with another friend, Vaidya Shikha Prakash, an ayurvedic consultant. “In this particular season the doshas of pitha and vaatha are aggravated,” shared Shikha, elaborating on the importance Ayurveda places on both butter and ghee and the procedures and modes of preparation detailed for both these ingredients in the texts. “Ghee is considered one of the most nourishing foods, based on its nature. It improves the strength of agni, the digestive fire. It is deeply penetrative and nourishes the tissues, and it also aids with the absorption of nutrients from other foods. Ghee is recommended for all seasons and all ages. It also alleviates dryness, prevents the increase in vaatha, and is one of the best medicines for high pitha.”

The same is said to be true of urad. Not only does urad have a very important place in the Uttarakhand diet, but it is a must on Ghee Sankranti. “In this season we experience elevated vaatha in the system, causing low energy, deterioration of the digestive fires, decline in appetite, and increased flatulence,” says Prakash. “Because of its nourishing properties urad dal assists with decreasing vaatha and increasing kapha. Additionally, ayurveda has a category of foods called santarpan janye dravye, substances that are superfood-level strengthening. Urad dal is in that category. It is also considered ushan virya and madhurasa, which means it starts being digested the moment it is consumed.”

Learning about Ghee Sankranti brought home to me how elegantly traditional Indian culture intertwines and balances work-life balance. Every laborious agricultural cycle, be it sowing or harvesting, is followed by celebrations and festivals to rejuvenate the spirit and soil, filled with fasting, feasting, and food traditions. But most importantly, the systems go beyond just being mindful of the health and well-being of all, the individual, the family, the community, and the earth. With every spoonful of ghee we drizzle onto our children’s meals, we carry forward centuries of traditional wisdom that we should pass on as well.