If it ain’t over until the fat lady sings, it isn’t really over until one’s successes or failures are made fun of by a Tamil comedian.

In a scene from the movie Kadhal Sadugudu, actor and singer Paravai Muniyamma asks her grandson (played by the late comedian Vivekh) to give her food, specifically rice. Instead, Vivekh pours a box of Kellogg’s Chocos on her plate, which Muniyamma says resembles keppai or grains of finger millet used in making koozh (porridge), a popular breakfast in Tamil Nadu. In this scene, it is evident that cardboard-y flakes of Kellogg’s breakfast cereal – even if it’s dosed with sugar and chocolate – is no replacement for the far tastier and more nutritious koozh, which is sometimes eaten with chinna vengayam (pearl shallots) and pickle; sometimes vellam (jaggery), and sometimes kudal kuzhambu (goat tripe curry) in the state.

Kellogg’s, the mammoth brand best known for its breakfast cereal originated in the United States, and made its first foray into the Indian market in the early 90s, a time of economic upheaval in the young Indian nation-state.

In 1991, India’s economy liberalised – enabling foreign brands to enter its market, and suddenly, high economic growth seemed possible. Consumers were flooded with choices in food products, and in other realms. In the 90s, with the opening of the country’s economy and culture – legacies of the past had given way to novelties of the future.

One of those novelties was breakfast cereal, which was introduced by Kellogg’s. The company first entered the Indian market in 1994 with its signature cornflakes, wheat flakes, and Basmati rice flakes. But despite successes elsewhere, the future would tell the story that – whether frosted, sweet, or flavoured – Kellogg’s cereal didn’t stand a chance against traditional Indian breakfasts in any way. Kellogg’s was first envisioned in the early 1900s by Dr John Harvey Kellogg, who made the flakes from wheat berry dough, as part of a health regimen and religious reform for the patients of Battle Creek Sanitorium – a world-famous wellness retreat in Michigan, that was based on the health principles advocated by the Seventh-day Adventist Church. In 1906, Dr Kellogg’s brother, Will Kellogg started the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company. This venture eventually became Kellogg’s, a brand that would not only sell cereal, but also Pringles, Pop-Tarts, and biscuits in the years to come.

Kellogg’s was first envisioned in the early 1900s by Dr John Harvey Kellogg, who made the flakes from wheat berry dough, as part of a health regimen and religious reform for the patients of Battle Creek Sanitorium – a world-famous wellness retreat in Michigan, that was based on the health principles advocated by the Seventh-day Adventist Church. In 1906, Dr Kellogg’s brother, Will Kellogg started the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company. This venture eventually became Kellogg’s, a brand that would not only sell cereal, but also Pringles, Pop-Tarts, and biscuits in the years to come.

In the years between its founding and its entry into India, the company went through several changes. It built factories in Australia and England in 1924 and 1934 respectively, came out with its iconic malted corn and sugar-coated Frosted Flakes in 1952, and introduced Sugar Smacks (now called Honey Smacks, which are puffed wheat with sugar content that can put a glazed donut to shame). Also by 1992, Kellogg’s established a presence in 150 countries around the world. A New York Times piece, written just after the company’s entry to India, notes that the overseas share of Kellogg’s revenues “had risen to 40 percent [in 1994] from 34 percent in 1987” while overseas sales accounted for “36 percent of Kellogg’s estimated pretax earnings of $ 1.1 billion”. In short — Kellogg’s was a mammoth operation at home setting sights on an ambitious expansion overseas.

This provided sufficient reason to launch in India. Besides the promise of a large, unexplored market, India had a fast-growing middle class, which other international brands like Coca-Cola and Frito-Lay were rushing to capitalise on. And Kellogg’s had a novel product – breakfast cereal – that was yet unheard of by consumers in the subcontinent.

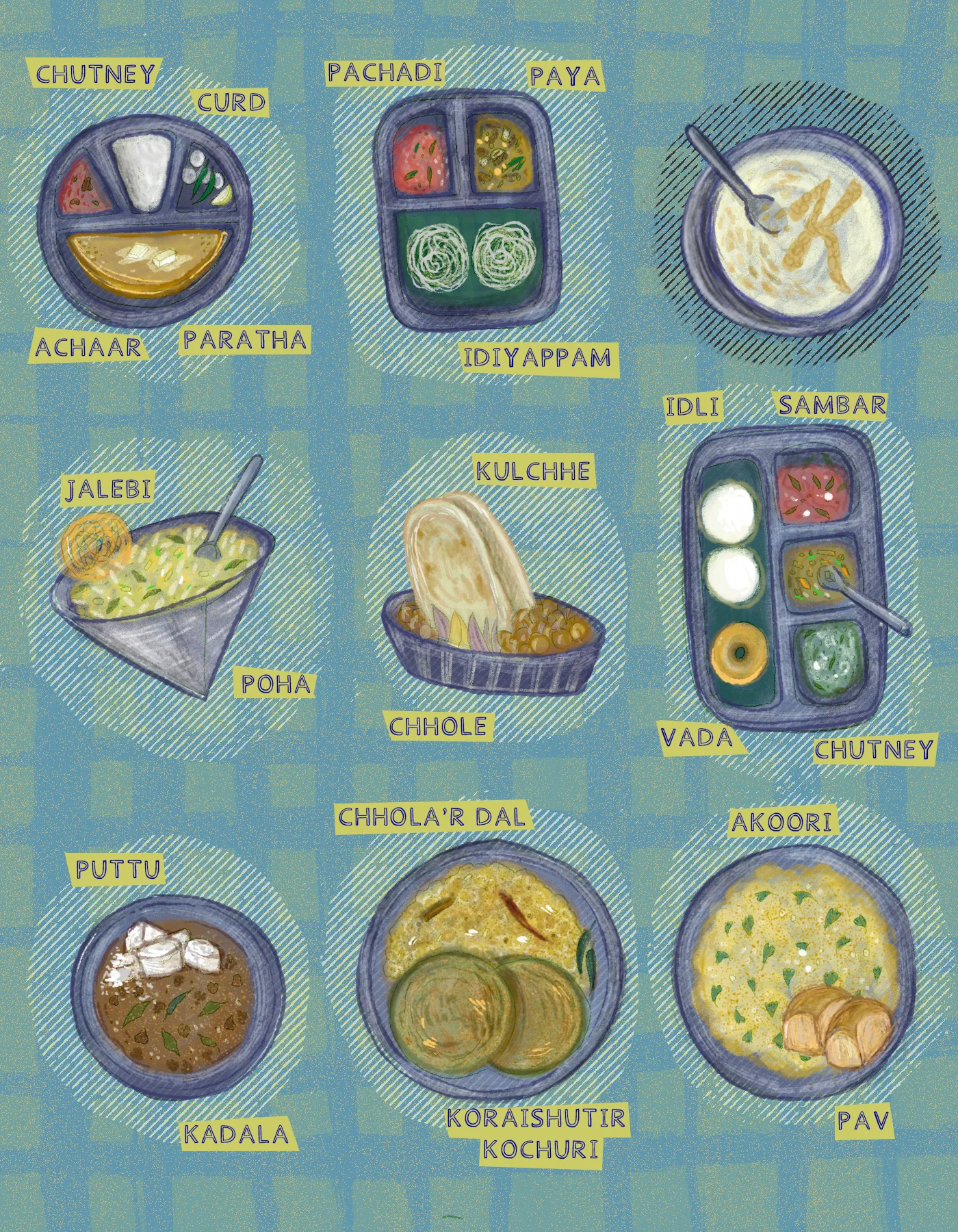

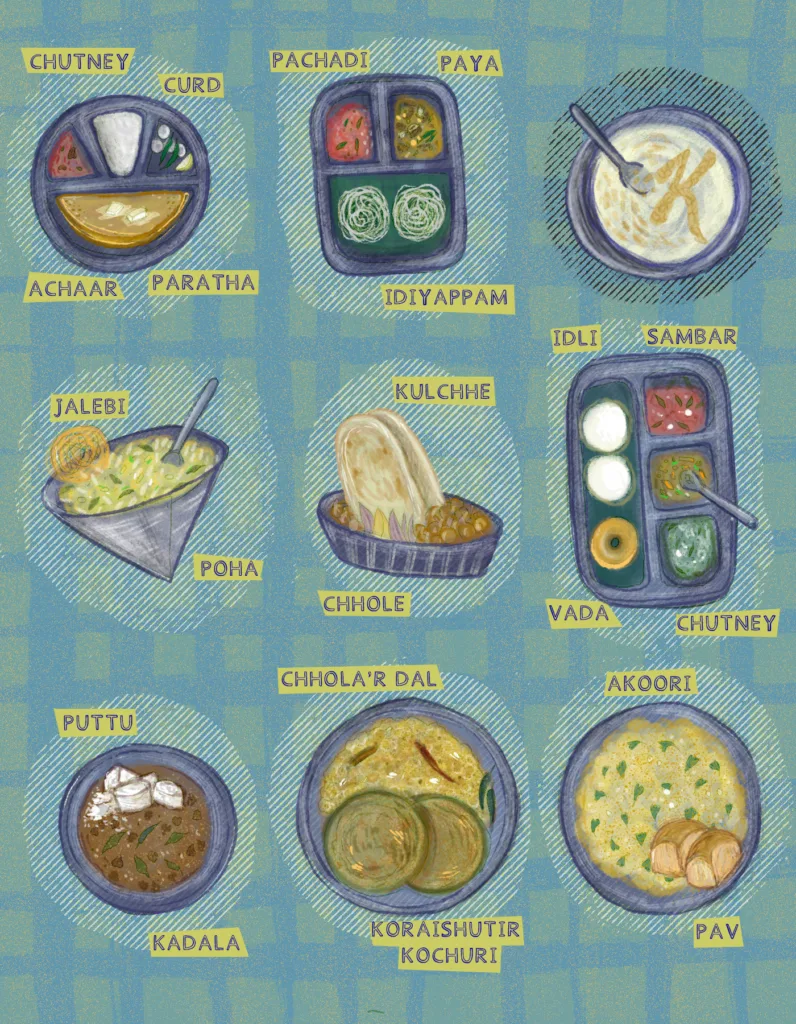

However, it is breakfasts like koozh – and also kali, idli, dosai, parotta and kuruma, luchi, pakhala bhat, puttu, kappa, poha, aloo paratha, sausage pao, and pyaaz kachori – that Kellogg’s aimed to disrupt in the first place. Such a diverse palate and abundant range of breakfasts became a formidable adversary. The company failed right after its introduction in the Indian market in 1995, and could only convert about 0.01 percent of the country’s 950 million potential consumers.

Moreover, Indians were used to consuming hot breakfast irrespective of the weather – and so cold milk on dry flakes just didn’t cut it. By then, Indians had also developed an affinity to condensed, sweetened milk, and trying to dissolve sugar in a cold liquid was frustrating as ever. And since most Indians boiled milk, even when it was pasteurised, warm milk on cornflakes resulted in a soggy, displeasing breakfast. The oft disparaged upma, in comparison, seemed to be much better.

When it first came knocking, Kellogg’s positioned itself as a healthy alternative to ‘indulgent” Indian breakfasts, and wanted to establish a monopoly outside North America. But despite setbacks, the brand has been ever-present, evolving and adding to its repertoire of breakfast cereal.

In 1996, two years after their initial launch, Kellogg’s came up with Chocos, a concave chocolate cereal aimed at fussy, school-going children; and by extension their middle and upper middle-class parents who would most likely indulge their kids’ demands. A year later, they introduced Frosties, again aimed at the same audience who reserved a curiosity for all things imported and lapped up new goods that indicated luxury and aspiration.

Simultaneously, Kellogg’s also looked to summon Indians’ sensibilities, by localising global products. In 1998, they attempted to adapt to Indian tastes by launching Mazza cornflakes in flavours such as mango-elaichi, coconut-kesar, and rose. And in the same year, Kellogg’s introduced its flagship cornflakes as a 500 grams family pack, and marketed Mazza in smaller quantities, which was desirable for those unaware of the product, but positioned an incentive to try it.

By the start of the new millennium, they also offered a wide range of sizes. This was a significant decision: Kellogg’s was competing with a homegrown brand, Mohun’s New Life, which was able to offer large-sized packs at affordable rates, unlike Kellogg’s that priced its products at a premium. But still, this did not clinch the win for the company. Kellogg’s did not make the mark it desired. Undeterred, Kellogg’s continued – in the mid 2010s it released noteworthy television and newspaper adverts, which remain crucial in selling food. Actors like Karishma Kapoor, Juhi Chawla, Sakshi Tanwar, (all mothers, of course) emphasised the importance of nutrition to other mothers; while on the other hand, Deepika Padukone (in a glittering red sari), was recruited to hammer home the selling point of a slim waist to countless young women who looked to the West for diet inspiration of diet-friendly foods.

Undeterred, Kellogg’s continued – in the mid 2010s it released noteworthy television and newspaper adverts, which remain crucial in selling food. Actors like Karishma Kapoor, Juhi Chawla, Sakshi Tanwar, (all mothers, of course) emphasised the importance of nutrition to other mothers; while on the other hand, Deepika Padukone (in a glittering red sari), was recruited to hammer home the selling point of a slim waist to countless young women who looked to the West for diet inspiration of diet-friendly foods.

In 2019, Kellogg’s went back to the drawing board to try again, and in consultation with celebrity chef Ranveer Brar, they launched three new variants of cereal in thandai badam, kesar pista badam, and rose-badam flavours. They claimed these new entrants brought “the authentic real flavours that Indians miss, and evoke a sense of nostalgia”. The new cereal was also available on e-commerce platforms such as Amazon and BigBasket, a sign of moving with the changing times.

Ironically, flavours like thandai, badam, rose, and kesar are associated with celebrations and festivals, and are not everyday breakfast ingredients. Besides, kesar, badam, and pista are expensive and are not accessible to everyone. So, to sell a 250 grams pack of kesar pista badam cornflakes at Rs 160 could possibly mean sub-par quality of the star ingredients. (A gram of kesar costs more than the pack of kesar-flavoured corn flakes!)

Finding it tougher still to conquer the Indian palate, Kellogg’s gave in and introduced two versions of upma in 2020: a regular version with chana dal, peanuts, and cashews; and a veggie-filled version with mixed spices. Given how it entered the Indian market with the intention to revolutionise the way we eat breakfast, the inverse seems to have happened. Kellogg’s resorted to change the way it does business in India – by cashing in on traditional cooking skills and age-old methods of knowledge transmission. In India, food has more often than not been determined by caste, family, faith, and class, than by strategic individual choice.

In India, food has more often than not been determined by caste, family, faith, and class, than by strategic individual choice.

Brands have moulded themselves to changing preferences, as well as succumbed to homogenisation instructed through caste and religious networks through the years. Consider that McDonald’s didn’t just come up with signature burgers like McAloo Tikki and Maharaja Mac; it also swapped regular mayo with an eggless version, used local spices and chillies, non-hydrogenated cooking oil instead of beef dripping for fries, and introduced affordable items to cater to a young Indian population restless for more.

When it rushed into a newly liberalised India, Kellogg’s failed to take into account these hardwired traditions, hierarchies, and rules surrounding food. It tried to create its own standards and override local knowledge of food consumption by introducing breakfast cereal that was ready-to-eat and “nutritious”. In comparison, it viewed the country’s wealth of diverse, traditional, and regional foods as time-consuming, unhealthy, and inconvenient, ignoring the ethnography, and culture of the place, and attempting instead to modernise diets through advocating a reliance on bland, processed food.

Because there is no one way to eat breakfast in India, there was no one dish that Kellogg’s could overcome. Take aval for example, or more commonly known as poha. These parboiled and flattened rice flakes, which have been present since the Tamil Sangam, have been consumed in myriad ways long before Kellogg’s patented and marketed its breakfast flakes even as mass-produced goods flooded the market throughout the next decade. Kellogg’s assumptions that everyone in India would eat cornflakes for breakfast – that is, to assume that everyone would eat the same breakfast – or that everyone eats breakfast were colossal mistakes.

In India, where there is no one standard cuisine, where regional cuisines are distinct from one another, where home-cooked food is held in great value and instructions are passed down in a piecemeal manner, we’re yet to see the day a singular breakfast dish become the overarching norm. And as long as fresh poi, hot idlis, and stuffed kachoris are still available and accessible – perhaps, we never will.